Every year, since the early fourth century, the Catholic Church has celebrated the Feast Day of Saint Sebastian on January 20. This Christian, who suffered martyrdom for his faith around the year 300 AD, became a queer icon in the 19th century and in that role has become one of the best-known saints.

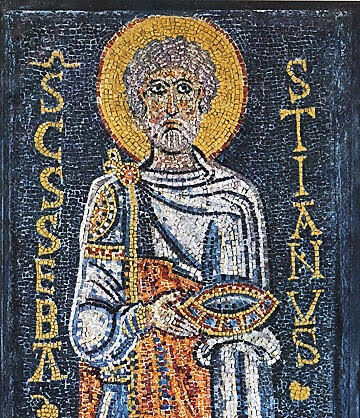

In accordance with fifth-century legends, early depictions from the sixth century onward show us Sebastian as a dignified and elderly soldier. So how did this initially inconspicuous soldier-saint become an icon for queer desire and life?

We know almost nothing about the historical figure of Sebastian. In a sermon on the saint’s memorial day (ca. 386-88), the church father Saint Ambrose, Bishop of Milan, reports only that Sebastian came from Milan and suffered martyrdom in Rome. At this time, pilgrims were already visiting his tomb in the catacombs on the Via Appia.

In the more novelistic records of martyrdom, which includes some fictitious stories about the saints, Sebastian appears as an officer of the imperial guard (cohortes praetoriae). He performed “daily diligent service to Christ” in secret, encouraging many martyrs to hold on to their faith steadfastly. When he was subsequently denounced, Emperor Diocletian, responsible for an empire-wide persecution of Christians, ordered Sebastian to be bound and then killed by being shot with arrows.

This scene will become important later. Sebastian manages to survive the arrows, while being raised up, in Christ-like fashion, and nursed back to health by Saint Irene. He returns to the palace, again accuses the emperors Diocletian and Maximian of unjustly persecuting Christians and is subsequently bludgeoned to death.

Why was Sebastian not lost to history like so many other saints? His tomb was located near a memorial to Saints Peter and Paul, and above it, the Emperor Constantine had a magnificent basilica built. (Since the ninth century, this church has borne the title of S. Sebastiano ad Catacumbas.)

Sebastian also became the third patron saint of Rome. His further fate, however, was decided only in the seventh century. According to sources, in 680, the plague raged in parts of Italy, including the city of Pavia. In a kind of diplomatic mission, the pope sent relics of this prominent Roman saint to the north in order to show his support. An altar was erected to Sebastian and the plague was miraculously defeated.

In the early Middle Ages, the image of Sebastian martyred by soldiers with arrows emerges as a typical representation of the saint. But Sebastian did not become a central figure in the life of the church until the 14th century. Once again, Europe is ravaged by the plague. This is the turning point. It should be recalled here that, in The Golden Legend, a popular compendium of stories of the lives of the saints, the story of the miracle of Pavia was told. And if Sebastian could help then, why not many centuries later?

Thus, more and more images of the saint bearing his arrows appeared, decorating numerous altars. The arrows acquired a new meaning: In ancient times (as at the beginning of the Iliad), arrows were used to send plagues among people. In the Bible, it is partly God Himself who punishes people for their sins. “For the arrows of the Almighty are in me; my spirit drinks their poison; the terrors of God are arrayed against me” (Job 6:4).

Sebastian is also hit by arrows—but he survives. He represents suffering and thus awakens hope for redemption. The decisive step is, however, still missing. It first needed to be introduced by art.

Oscar Wilde is not alone in his adoration of Sebastian. Many other sexual outsiders are also fascinated by him: Thomas Mann, in Germany; Yukio Mishima, in Japan.

If the old mosaics show us an older, bearded and clothed warrior, in the Renaissance, Sebastian begins to appear as a young, beardless and unclothed man, since the armor of the soldier would have stopped the arrows. As soon as the scene of the first martyrdom comes into focus, Sebastian has to undress, becoming a beautiful youth. In this way, he embodies the hope of a wholesome body that the plague cannot overcome.

In addition, the contemplation of beautiful things was thought to form a kind of medicine that strengthened the defenses against disease. Because Sebastian passively endured the arrows, and passivity was connoted with femininity, Sebastian acquires traditionally “feminine” features—curly hair and red cheeks.

In the legend, it is said that after being pierced by arrows, Sebastian looked like a hedgehog. In the Renaissance and Baroque eras, this image faded considerably. The image of Sebastian often approached that of Christ: two unclothed men whose physical torture brought redemption. The artistic liberty depicting young male bodies went so far as to raise concerns that such images might evoke sensual pleasure instead of religious edification.

Pious theologians were adamant to put a stop to what they saw as offensive images. But the emancipation of artists from the strict guidelines of their patrons progressed. The young and beautiful Sebastian could no longer be stopped. Religion lost control over art.

In the 19th century came Sebastian’s hour as a queer icon. The Roman martyr and plague saint became a figure of identification and protest. Sebastian was not gay, and his sexuality plays no role historically. Whether the artists who eroticized him were gay can no longer be determined.

One of the most famous depictions of Sebastian, that fascinated generations of later artists, was painted by Guido Reni in the 17th century. During the Holy Week of 1877, Oscar Wilde, with friends in Genoa, visited the Palazzo Rosso to look at Reni’s painting. Weeks later, they were in Rome and visited the grave of the poet John Keats. Wilde later wrote in “The Grave of Keats”: “The youngest of the martyrs here is in lain / Fair as Sebastian, and as early slain.”

Wilde later recounted how Reni’s Sebastian appeared in his mind’s eye: “a lovely brown boy, with crisp, clustering hair and red lips, bound by his evil enemies to a tree, and, though pierced by arrows, raising his eyes with divine, impassioned gaze towards the Eternal Beauty of the opening heavens.”

Wilde’s penchant for Catholic rituals is well known. He saw these rituals, along with aesthetic creativity, as a counterweight to a “disenchantment of the world,” as the German sociologist Max Weber wrote. In this way, Sebastian was a countercultural figure for Wilde.

In his late exile, and through his death, Wilde called himself “Sebastian Melmoth.” In a sense, he cloaked himself with Sebastian and revealed how he identified with this ancient troublemaker.

Wilde is not alone in his adoration of Sebastian. Many other sexual outsiders are also fascinated by him: Thomas Mann, in Germany; Yukio Mishima, in Japan, among them. Sebastian, then, becomes part of a code. Anyone who decorates his apartment with a picture of him reveals his own identity to insiders. In this way, Sebastian becomes an open secret.

The arrows become ambiguous: they stand for the painful arrows of unjust persecution as well as for the pleasurable arrows of erotic desire. Sebastian can be interpreted by some as a bound Eros. Pointing at him represents a kind of protest.

By the beginning of the 20th century, Sebastian was established as a queer icon. More and more images emerged. He appeared eroticized in movies. He offers the possibility to articulate identification and protest, not only to queer people, but to others as well.

The arrows become ambiguous: they stand for the painful arrows of unjust persecution as well as for the pleasurable arrows of erotic desire.

Because injustice and misfortune can happen to anyone and everyone, and no one is safe from becoming their victim, Sebastian becomes a universally understood image.

In the dramatic first years of the H.I.V./AIDS crisis, when the diagnosis in many cases represented a death sentence, and gay men were marginalized and treated with hostility by secular and religious authorities, the suffering queer Saint Sebastian became an iconic figure. The paintings created during these years, for example, by the New York artist David Wojnarowicz, continue to impress today. They show more empathy for the countless people affected and protest louder against AIDS policies than most theological texts of the time.

As the arrows of the soldiers hit Saint Sebastian, the arrows of injustice hit the sanctity of the human person. This is what marks the beginning of the theology of martyrdom: the victims of injustice become victors because God is on their side.

A German-language version of this article is available here.