All you need to do is look around and you will see that intentional, unwanted and aggressive behavior, usually where a power dynamic exists and more commonly referred to as bullying, is on the rise. Although bullying behaviors may begin in childhood, it does not magically disappear when someone turns 18, nor do the side effects from the trauma evaporate. The pain and hurt from those unwanted and aggressive behaviors often causes physical and emotional scars that last a lifetime.

Bullying is a complicated phenomenon that is often the result of multiple factors. There is not one simple cause but one thing is certain: Youths are being exposed every day to the ever-increasing normalization of hostile behavior, in person and on large and small screens alike.

This includes the constant exposure to divisive, fear-driven tactics of political rhetoric, as well as dogmatic teachings that instills fear, hate, shame or a selfish ambition to be “better” than someone else at all costs. Bullying behavior can sometimes be a learned escape mechanism; those who have been targeted by an aggressor will become the aggressor to escape the pain of being targeted.

One of the most common tactics is to target someone else’s differences. Although there are many different physical, emotional and intellectual attributes for which youths are targeted, the most frequently cited differences in youth bullying are sexual orientation and gender identity. According to a 2019 report from the C.D.C., 43 percent of transgender youth reported being bullied at school, while over one-fifth of gay and lesbian youths reported attempting suicide.

This is no small problem, with a nearly two million school-age LGBTQ youths in the U.S. in 2020. This is an issue that needs to be discussed, and resources need to be made available to this vulnerable population.

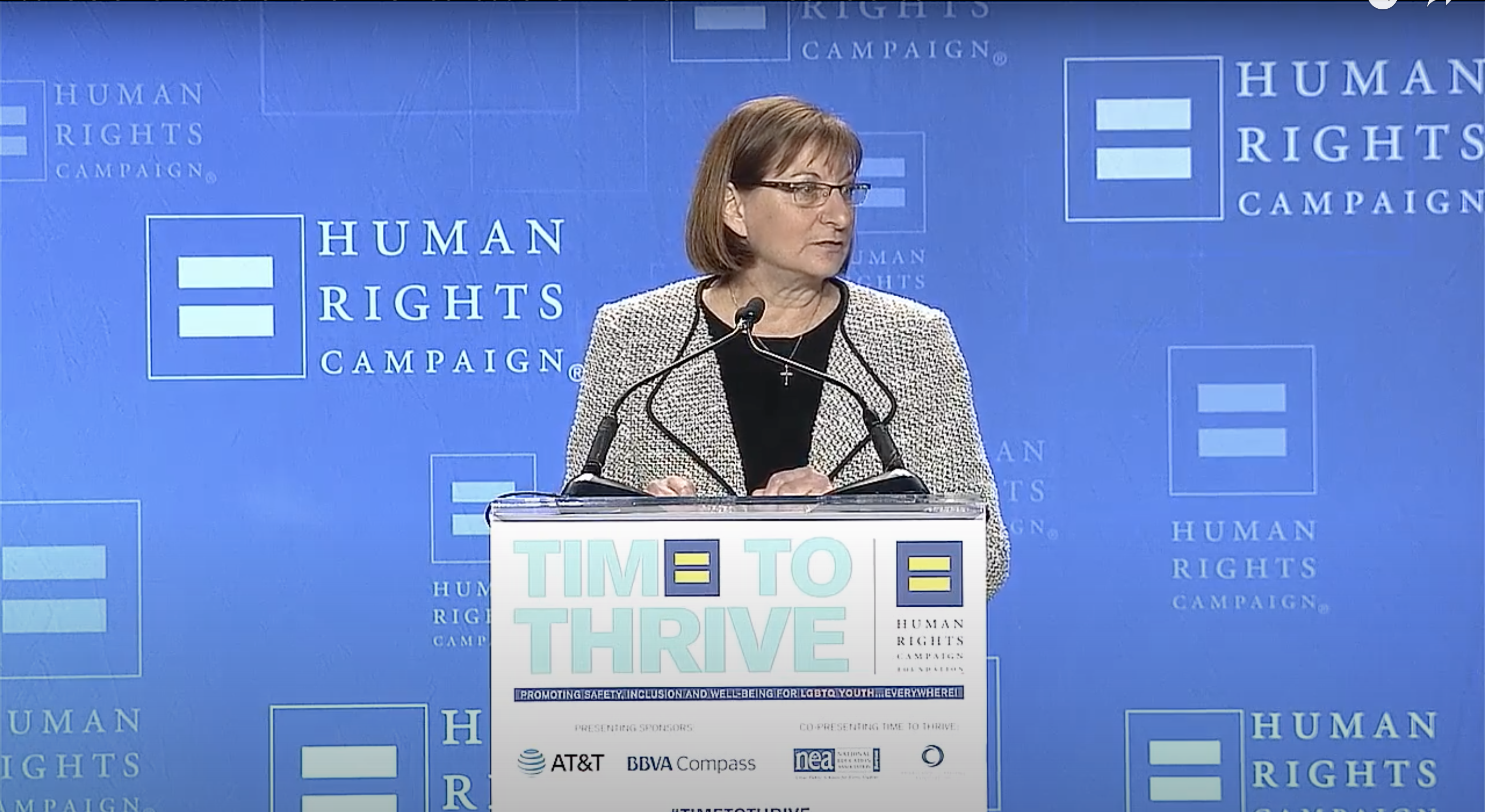

The consequences of this kind of harassment and humiliation lead to many additionally significant statistics, reported by the Human Rights Campaign in 2019.

29 percent of transgender youth have been threatened or injured with a weapon on school property, compared to 7 percent of cisgender youth

29 percent of gay or lesbian youth and 31 percent of bisexual youth have been bullied on school property, compared to 17 percent of straight youth

Transgender youth were more likely in 2019 to have been bullied on school property than reported in 2017.

I hope these horrific numbers grab your attention. I know they tug at my heart, but that is probably because the topic of bullying is very personal for me. My son Tyler Clementi was a Rutgers University freshman who made national headlines after he had been the target of cyberbullying in the fall of 2010. Tyler’s roommate humiliated Tyler in front of his new dorm mates when he livestreamed my son in a very personal and private moment with another man.

The worst part is that I believe Tyler’s roommate did this simply because of Tyler’s sexual orientation. Tyler’s roommate targeted the one God-given trait that made my son different from him. I am not sure what his roommate was trying to achieve or even if he had any thought or care to the great harm he was causing to another human being. But his actions did have great consequences to my son.

Tyler was a thoughtful, kind, caring young man with many gifts and talents that, sadly. the world will never know. As Tyler kept reading the jokes and comments on social media, his reality became twisted and distorted. And he lost sight of how special and precious he was, as well the resources he had available to him, both at Rutgers and at home.

It was in that unbearable moment that Tyler made a permanent decision to a temporary situation, a terrible decision that we will never be able to change or undo. On September 22, 2010, Tyler died by suicide. He was 18 years old.

“According to a 2019 report from the C.D.C., 43 percent of transgender youth reported being bullied at school, while over one-fifth of gay and lesbian youths reported attempting suicide.”

As much as my foundation co-founder Joe and I wanted to go back and change Tyler’s actions, the reality was that we could not. Instead, we put our energy and actions into making sure no one else would have to suffer the same pain, shame or humiliation that Tyler did.

We started the Tyler Clementi Foundation to end all online and offline bullying in schools, workplaces and faith communities. We wanted not only to raise awareness around the issues that impacted Tyler, but we wanted to find actions and solutions to those issues based on research.

Looking back, one of the things that stood out as we learned more of what had happened at Rutgers was how many people had been aware of what Tyler was experiencing. There were so many passive bystanders that said and did nothing. Silence is not acceptable. That is why I am so passionate about turning passive bystanders into active “Upstanders.”

An Upstander is someone who uses their voice, power and presence to intervene safely in a bullying situation. Because we never want anyone, especially youth, to come into harm’s way, we share different approaches to being an Upstander in a bullying situation, either by interrupting the situation, reporting the bullying behavior, and most especially, reaching out to the target to make sure they are safe.

We need to have these difficult conversations. I believe we need to share our stories and bring these difficult topics out into the light. Talking about mental health issues, like bullying, depression and suicide, do not increase their prevalence. But rather, it is by having healthy conversations that we will reduce the shame and stigma associated with these topics and break down the barriers, enabling people to get the help they need.