Editor’s note: This article is the second part of a three-part series by the Rev. William Hart McNichols. The first part can be found here.

Part II

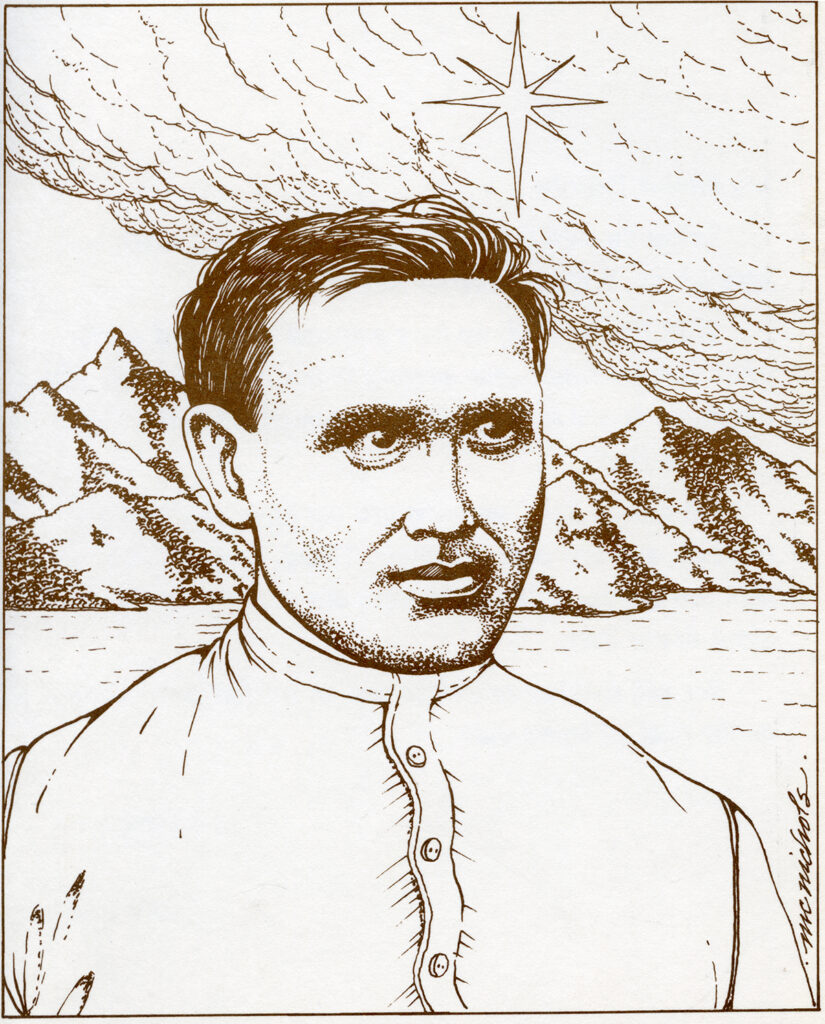

In August 1983, Dignity, a Catholic group that ministers to and advocates for LGBTQ people, called and asked me to celebrate the first Mass, to be held in September, for people with H.I.V./AIDS. When I hung up the phone, I knew this was not just a Mass. My whole life was about to change.

Simultaneously, I was finally ordered to move back into a Jesuit community, and the Rev. Joseph A. O’Hare, S.J., editor in chief of America magazine from 1975 to 1984, wanted me to move into America House and do illustrations for the magazine. And so, I moved to Manhattan and left my life in Brooklyn.

After the Dignity Mass, I was inundated with requests: “Will you visit my brother, my cousin, my lover, my friend?” My prayer had been answered. Ironically, I had been a chaplain that first summer at the Brooklyn-based Coney Island Hospital, near Sheepshead Bay, which I found very traumatic. I thought, “Well, I’ll never be a hospital chaplain!”

Also, the nurses at the hospital gave me a going-away present: a print done in Albuquerque by a Dominican artist, Sister Giotto Moots. Her print was entitled: “The Artist Being Saved By The Virgin Mary He Just Painted.” Her studio was in Old Town, an 18th-century settlement in Albuquerque, right across from where I’d move in September 1990, to begin my iconographer’s apprenticeship.

My first visit to a man dying of AIDS left me staggering onto the streets of New York. He was lying in a bed, visibly emaciated, with his mother on one side of him and his lover on the other. Both were weeping. His lover was dropping orange juice through a straw into his half-opened mouth, as if he was feeding a baby bird.

I didn’t cry until I left, and then the tears wouldn’t stop.

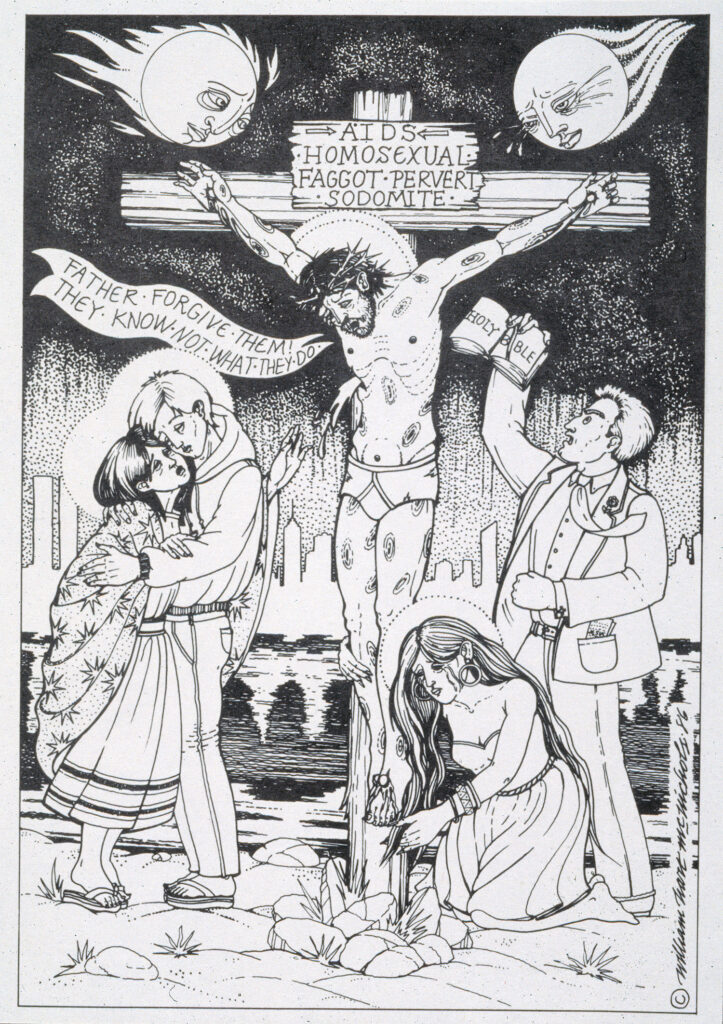

I knew two things: I had to be trained and I had to create a painting, aimed into the heart of the church, about the suffering I was seeing. I signed up for the training with Gay Men’s Health Crisis, founded in 1982 to provide counseling and social support for AIDS sufferers. The training answered all my questions and equipped me to go on.

I had heard that New York’s former Saint Vincent’s Hospital had a hospice, and I made an appointment with Sister Patrice Murphy. She gladly accepted me but said she couldn’t pay me except for subway money.

So I began my seven years as a hospice chaplain, first visiting some elderly cancer patients and a few men dying of AIDS. A few turned into 50, then 100 and soon hundreds.

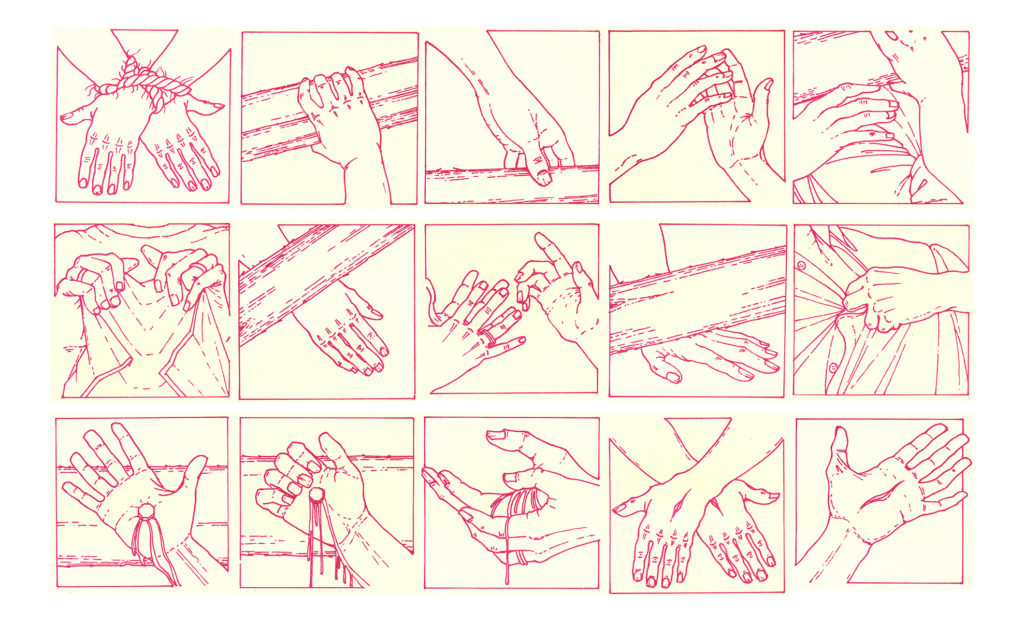

The doctors, nurses and caregivers were overwhelmed, exhausted and terrified by the human suffering and by medical complications they had never seen. And there was no vaccine or cure for any of the infections. All of this would later go into something I wrote and illustrated, entitled “The Stations of the Cross of a Person With AIDS.”

Next, in the conclusion of this series, Father McNichols writes: “At my home in New York, I found out that some members of the community were uncomfortable with me living there while I ministered to critically-ill H.I.V./AIDS patients. They were afraid I’d bring AIDS into the house through my daily contact with the dying.”