Below is an excerpt from Making Room: Three Decades of Fighting for Beds, Belonging, and a Safe Place for LGBTQ Youth. It has been edited for style and clarity.

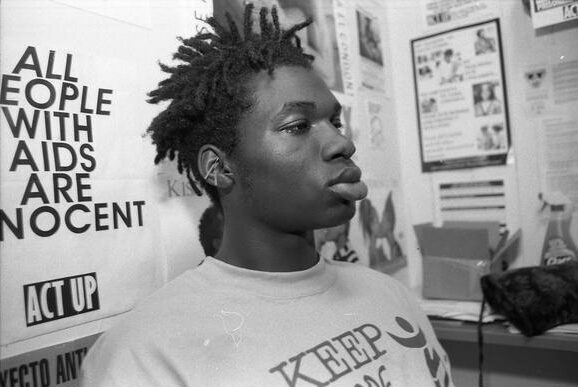

It was the holiday season of 1994 when I first met Ali Forney, a black nonbinary homeless teen who would transform my life. I had just become the director of SafeSpace, a Times Square based day program for homeless youths. As I describe in my book, Making Room, during my first weeks there, I was distressed to discover that none of the city’s few drop-in centers for unhoused teenagers remained open for Christmas. Unable to bear the idea of our youths left out in the cold on this day of love and togetherness, my colleagues and I volunteered to keep our program open for half the day.

I had come to SafeSpace after a decade of serving the homeless. I am a gay Catholic, and back then I was struggling to reconcile my faith and my sexuality after experiencing homophobic rejection in Catholic spaces. My service had always been rooted in the belief that Christ was especially present in those who were destitute. Knowing that a significant percentage of the young people at SafeSpace were queer, I hoped this new job might help integrate aspects of my life seemingly at war with each other.

On Christmas morning, we rolled out all the festivities. We decorated the dining room with wreaths and garlands, colored lights and flowers, and two dozen volunteers came to help from the church next door. These keen, strange new faces lined up behind steaming pots and platters, serving up a feast of foods and cakes and pies, and freeing up the staff to sit and eat with the young people.

Surely the truth of God’s limitless, all-welcoming love for every one of us is the burning heart of the Christmas mystery.

But the young people were uncharacteristically subdued, made shy by the many guests in the room. Most days, meals were boisterous affairs, with clients calling out across the tables, provoking endless bursts of laughter and verbal taunts. But now, even Ali spoke in quieter tones, without much of her usual bawdiness or shade-throwing. Having witnessed this phenomenon at many holiday meals since, I’ve realized that their shyness is a function of adolescence. Teenagers place huge stock on how they are evaluated by others, and generally feel terribly self-conscious about being pitied. Homeless teens are no different. Being observed by a large crowd of unfamiliar faces made our young people acutely aware of their destitution. Nonetheless, on my first Christmas at SafeSpace, I was glad the kids were indoors for a few more hours, eating their fill in a space of warmth and abundance.

However, it was awful when three o’clock arrived and we had to close the center. I marshaled everyone down to the lobby and watched Ali, and all of the others make their way out of our warm building and into the snowy streets. Later, after I’d locked the doors, set the alarm, and walked to my mother’s apartment on East Twenty-fourth Street, I couldn’t shake the kids from my mind. We’d given them backpacks and gloves and hats and scarves as Christmas presents, and they stood there in the lobby, wrapping their necks and covering their heads and fingers. Then they made their way into the street, most with nowhere good to go, little tufts of their hot breath forming icy clouds as they shuffled outside into the frigid air.

Something that deeply disturbed me was the preponderance of queer kids. On most days, about a third of the youths at our drop-in center were openly LGBTQ. But Christmas was a day when many parents or extended family members welcomed their homeless kids back for the day. When I saw that most of the kids with us that day were LGBTQ, it made me want to cry. Even on this holiday of family togetherness, the queer kids were not welcomed in their homes. Seeing those unwanted kids left to shiver in the streets, I understood the power of homophobia and transphobia to sever the bonds between parents and their queer children.

My first weeks at SafeSpace were a crash course in learning about youth homelessness. What a nightmare those kids were living through, out on their own, hungry, unsheltered, abandoned by their parents. Most parents are hardwired to nurture and protect their children. As I examined why those of the youths in our care had been unable to do so, I discovered it was usually due to some pathology. Many of our young people had parents who suffered from mental illnesses and/or addictions. But numerous others had parents whose homophobia and transphobia caused them to reject their children. Seen through a child-welfare lens, homophobia couldn’t fail to be recognized as a pathology that brought brutal harm to children.

What I saw tore at my heart, not just as a service provider, but as a Catholic. Most of the queer kids were left outside on that cold Christmas night because of their parents’ religious beliefs. I shared some of those beliefs. Yet here we were, treating people very differently. They were abandoned in the name of God. Forsaken on the great Holy day when we celebrate how God tenderly embraced humanity, in all our vulnerability and brokenness, through the birth of Jesus. As I sat with my family that evening, I thought of Ali and the others alone in the icy streets. A line from Silent Night, my favorite Christmas hymn, kept sounding in my mind:

Silent night! Holy night!

Son of God, love’s pure light

It was as if Ali and the rest of the LGBTQ kids were considered unworthy of their parents’ care, unworthy of belonging in their homes, unworthy of basic human compassion, unworthy of their place in love’s pure light. And a prayer began to well up within my heart, that I might find a way to witness that LGBTQ youths were worthy of the love that every child is due. Because every child is born to be loved. Surely the truth of God’s limitless, all-welcoming love for every one of us is the burning heart of the Christmas mystery.

Excerpted from Making Room: Three Decades of Fighting for Beds, Belonging, and a Safe Place for LGBTQ Youth by Carl Siciliano, published by Penguin Random House. Copyright © 2024 by Carl Siciliano.