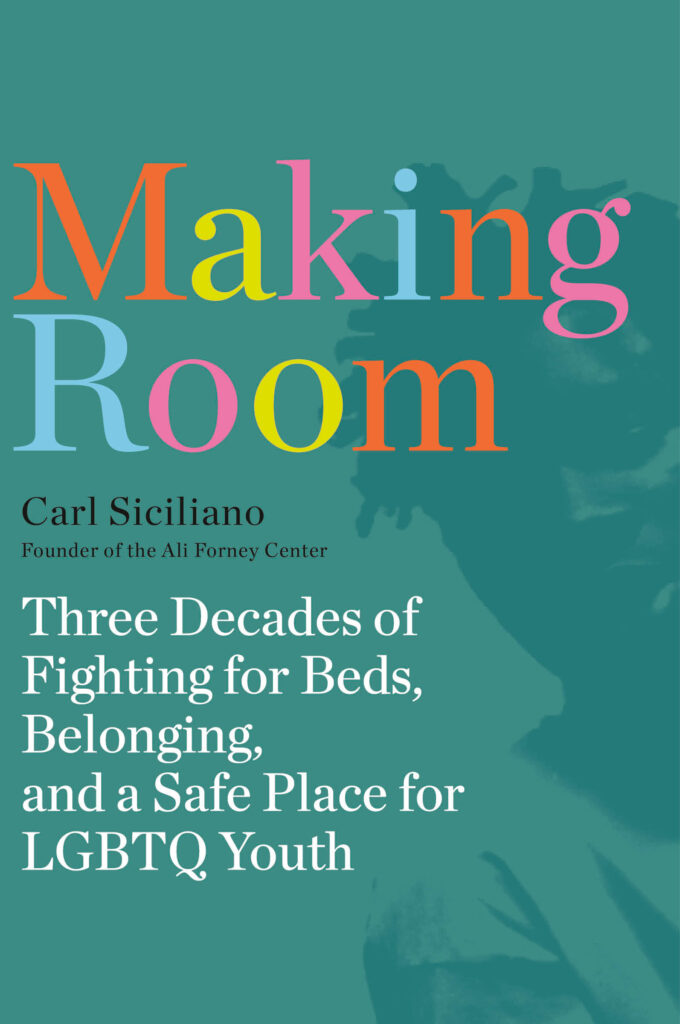

The following is an excerpt from Making Room: Three Decades of Fighting for Beds, Belonging, and a Safe Place for LGBTQ Youth. It has been edited for style and clarity.

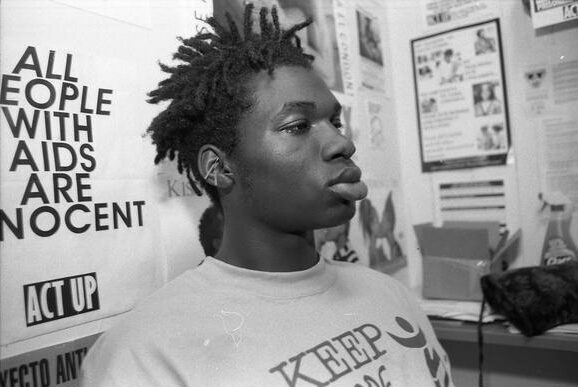

Outside. To be a homeless queer youth is to be forced outside in multiple ways. On the most basic level, these young people are forced to suffer the physical reality of sleeping outside. That was the reality for Ali Forney, who slept on a bench below the Metro North underpass on 125th Street in Harlem, not far from where they would be murdered on a cold December night back in 1997.

Ali Forney was a nonbinary Black youth I met in 1994 when I first became the director of a Times Square drop-in center for homeless teens. Ali, like thousands of other homeless queer youths I’ve come to know, was unwelcome in their devoutly religious home, and thus was forced outside.

Yet even before the rupture with their families, many queer teens are treated as outsiders.

I think of another young person, Laurence, a stocky kid whose hard, “homo-thug” persona was softened by warm, friendly eyes, telling me how his parents had devised an elaborately cruel ritual centered around food.

Ali, like thousands of other homeless queer youths I’ve come to know, was unwelcome in their devoutly religious home.

“Our family always ate meals together in the dining room,” Laurence said. “But after I came out, I wasn’t allowed to sit with them. They made me eat in the basement and wouldn’t let me eat on the plates or use their forks and knives.”

He continued, “For me it was only paper plates and plastic utensils. They made sure I knew that, in their eyes, I was some sinful diseased f— they needed to protect themselves from.”

Laurence felt so demeaned by this treatment that he chose to live in the streets. It was better to be homeless than to endure such humiliation.

“I left home to save my life. If I’d stayed there, no doubt I would have killed myself,” he said later.

That is a confession I’ve heard all too often during my 30 years of caring for unhoused teens.

When young people are inundated with messages that their queerness irrevocably positions them outside of their families, outside of their homes, outside of goodness, outside of human dignity and outside the reach of God’s love, many internalize their rejection to the point where they fear the only solution is to literally take themselves out.

I’m struck that the primary metaphor we use for the process of becoming truthful about our queer selves is “coming out.” We all come out of the closet, out of the dark spaces of hiding, out of shame. Yet for hundreds of thousands of our children, coming out of the closet leads to being forced outside to the streets. A double helix of chosen act and unchosen consequence, modes of outness bound together.

For hundreds of thousands of our children, coming out of the closet leads to being forced outside to the streets.

When I first began to work with homeless queer youths, I was bowled over by their integrity, by the tribulations they endured in the service of their inner truth. And now, decades later, I recognize in them a blazing spiritual sign. For I understand Jesus to be the God of the outsiders.

We are told Jesus was born outside, in a stable meant for animals. Before starting his ministry, he journeyed outside, into the wilderness, to do battle with evil. When he returned to his hometown of Nazareth, preaching his message of justice and liberation, his neighbors forced him out of the synagogue and dragged him to the edge of a cliff, intending to throw him to his death.

Jesus constantly befriended and embraced those held by his peers to be shameful outsiders—sex workers, tax collectors, lepers. He denounced religious systems that segregated people into the categories of righteous insiders and shameful outsiders, and this stance led the leaders of those systems to call for his death. The Roman soldiers crucified Jesus “outside the city walls,” the Gospels say. And we are told that when he died in excruciating pain, Jesus cried out from the agony of finding himself outside of God’s care: “My God, my God, why have you abandoned me?”

Jesus acted in radical solidarity, especially toward those considered by society to be unworthy of love. To follow Jesus means joining one’s life and motivations with the oppressed, with the unhoused, with the enslaved, with the colonized, with the queers. Whenever anyone is treated as if their life doesn’t matter, Jesus goes outside with them. Living my life in service to queer youths thrown out of their homes has been an act of adoration to the Christ of the dispossessed.

Living my life in service to queer youths thrown out of their homes has been an act of adoration to the Christ of the dispossessed.

Ali Forney had as profound a realization of God’s all-compassionate, all-merciful love as anyone I’ve ever encountered.

“God loves everyone for who they are!” Ali cried out during our program’s annual talent shows. Each year Ali used them as a vehicle to make a rapturous proclamation of faith in a God who embraces us in our queerness. “God has mercy on all people!”

It was June 1997, just days after Ali’s final show before their death. Our crew was marching in the Pride Parade. Back then, the parade always got off to a contentious start, for the first thing we passed was a large crowd of Catholics who always stood outside of Saint Patrick’s Cathedral on 50th Street, carrying signs that proclaimed we were going to hell.

Ali was never one to remain silent in the face of slurs. They strode right up to the barricade and began to strike poses, blowing lewd kisses toward the detractors and hiking up their blue denim miniskirt to show their skinny ass.

“Shame!” they cried out. “Shame on you, you sick pervert!”

Ali became enraged.

“No, shame on you! Who are you to condemn me? I am a child of God!”

Our group’s coordinator, fearing the conflict might escalate to violence, ran over and grabbed Ali, pulling them away from the protesters.

“Come on, Ali,” he counseled, “Don’t let those a—holes rain on your parade.”

“I’m not letting nobody tell me I’m not a child of God!” Ali answered. “Nobody!”

God’s heart was the only space Ali trusted they could not be cast out from.

How many times in the years since then, when my own faith has seemed in danger of withering, have I held to that memory of Ali’s confidence in the radical inclusion of Divine Love? God’s heart was the only space Ali trusted they could not be cast out from.

As a teenager, I converted to Catholicism, hoping to find support and guidance for the spiritual journey. Spiritual traditions aim to be vehicles of transmission, passing on the hard-won realizations of their founders.

But as I grew older and sought what it meant for me to follow Christ as a gay person, I struggled to find Christ’s all-embracing love in the churches and spiritual communities I’d turned to for support.

I recall what happened at the Catholic Worker community in New York City I’d joined a few years after Dorothy Day died.

It was the mid-1980s, the height of the AIDS crisis. Many of us were pleading for our Catholic Worker community to extend its advocacy for society’s outcasts to an LGBT community under siege. But they adamantly refused. I remember how an openly gay man was expelled from a leadership position because he dared to question church teaching on homosexuality.

Even in the most marginal spaces where I sought to follow Christ—such as in Catholic Worker Houses and in monasteries—I met many wonderful and dedicated people, but it seemed like the transmission of the spirit of Jesus was too often blocked by rigid fetishizations of authority and tradition.

Again and again, I encountered the message that church teaching was to be valued over the love and acceptance of God’s queer children.

I struggled to find Christ’s all-embracing love in the churches and spiritual communities I’d turned to for support.

More than any church “insider” I ever met, Ali gave me the spiritual transmission I’d been searching for. Witnessing Ali’s utter confidence in an all-merciful God helped me learn to trust that the queerness of the youths, and my own queerness, were reflections of the queerness of God. The God of love. The God of the outsiders.

Part of me longs for certainty. That longing was satisfied for a time in my youth, when the structures and community of organized religion helped make the journey seem more tangible.

When I decided to bring my whole self into my spiritual quest, I was forced to leave many religious certainties behind. Often, my journey of faith has felt like stumbling through the wilderness in the dark of night, wandering into thorn bushes, falling into ditches. Yet, the fact that my queerness marginalizes me from my spiritual home has begun to seem a blessing, rather than a curse. This I learned from Ali and the other youths: To be cast outside is to walk on holy ground.

Excerpted from Making Room by Carl Siciliano, published by Penguin Random House. Copyright © 2024 by Carl Siciliano.

0 Comments