“I wanted to let you know that my Aunt Carol passed away this morning,” read the email I opened earlier this fall.

My heart sank.

Carol Baltosiewich’s story had been a part of my life since 2016, when she and I first spoke on the phone. I had discovered in a dusty university archive a short Associated Press article about her work doing HIV and AIDS ministry in the 1980s. I was just beginning research into a project about the Catholic Church’s response to AIDS and the idea of a Catholic sister from a small city in the middle of the country opening an AIDS resource center caught my attention. I eventually tracked her down and she agreed to a phone interview. We’d have many more over the next few years and her story would go on to feature prominently in my podcast “Plague” and then in my book, Hidden Mercy.

Months sometimes passed in between our conversations, but we stayed connected. Each time we spoke, Carol revealed a bit more of her story.

Carol had grown up in a staunchly religious, Polish-Catholic household. She joined the Hospital Sisters of St. Francis in 1963 and trained as a nurse. She eventually worked in the I.C.U. and E.R. before moving to Belleville, Ill., to offer homecare nursing. There Sister Carol began to encounter young men dying from a strange new disease and wanted to help. She and another member of her religious community, Sister Mary Ellen Rombach, relocated to New York City for a few months to learn about the relatively-new AIDS epidemic. They returned home to open what would become one of the largest HIV and AIDS resource centers in the Midwest, Bethany Place. Sister Carol, who described herself at that point in her life as a “conservative Polish nun,” went on to become an unlikely ally and friend to countless gay men dying from AIDS during the height of the crisis.

Our phone calls and emails became more regular as I continued writing my book and I was fortunate to have the chance to visit Sister Carol twice.

The first time, I took the train from my home in Chicago down to St. Louis, then drove over to Belleville, and spent a day and a half with her. We crammed in as many interviews as we could, with Carol acting as something of a fixer, finding me other people to tell their stories that would also end up in my book. It was exciting, frustrating, moving and inspiring all at once.

One moment in particular from that visit has lodged itself into my memory.

It was our first day together and our time was winding down. Carol was growing tired and I wanted to return to my hotel to prepare for the back-to-back interviews scheduled for the next day. But Carol asked me to hold on. She walked to a closet in her modest apartment and came back with a photo album. She wanted to show me photos of the young men whose stories she had just shared with me, most of them in their 20s and 30s, each of them experiencing the tumult and desolation that accompanied a diagnosis of HIV in the 1990s.

Carol’s fingers, warped by age, slowly caressed each page. She voiced some of the names aloud, recalling a character trait or quick anecdote. She would sometimes smile, recalling happier occasions before illness took its toll. All these men had lived unique lives, which had been cut short decades earlier, but Carol kept their memories alive. She lamented that so many of them died so young. And she invited me to share her memories of these men with my readers.

A few years went by. My book was finally published and it received some positive attention, especially in LGBTQ and Catholic circles. I was fortunate to embark on a book tour that eventually took me to more than three-dozen cities. During each of these talks, I explained that when I had begun my research, I was somewhat closeted, at least publicly, and would still get nervous when identifying myself as a gay man. I worked in Catholic spaces, which isn’t always easy for openly gay people. During my initial call with Carol, I was reluctant to reveal too much about myself. But Carol reasonably asked why I was interested in her ministry. After all, decades had gone by since she had left Bethany Place.

I felt in that moment that I was being given a glimpse of the tenderness that she had shown to the many young men whom she accompanied in their final days.

I mustered up the courage to say I am gay and Catholic and that I wanted to know more about this time in history. Carol was nonplussed, said something like, “Of course, that makes sense,” then opened up.

Identifying myself as gay and Catholic has gotten easier over the years, in part because of Carol. When I found myself in St. Louis for a book event, back in 2022, I built in time to visit Carol.

We sat for about an hour in her apartment. I thanked her for sharing her story with me, in part because her generosity had encouraged others to share their stories with me as well. She said that the pleasure was hers, partly because she was happy to hear that her ministry was helping an entirely new generation of people understand God’s unconditional love. Plus, she said, news about the book had prompted a handful of people she hadn’t seen in years to reach out to her.

As Carol and I hugged goodbye, I sensed that this might be our last encounter. Her health had been deteriorating and she seemed to be slowing down. Carol died on Sept. 18, at age 80.

A few weeks after I learned of Carol’s passing, I was in Rome, hosting an international gathering for Outreach featuring the voices of LGBT Catholics sharing their stories for senior church leaders. Rome can be heady: St. Peter’s imposing dome, cardinals and bishops strolling past on sidewalks and pilgrims from around the world bringing their own stories to God.

I thought of Carol who, during her life, had a complex relationship with the institutional church. She was an independent spirit and, like other holy people, she sometimes clashed with superiors while charting her own course. Still, she remained devoted to her faith. During what would be our final meeting, Carol told me that even in spite of her complicated feelings about the church, she would die a Catholic.

It was with this in mind that, following a meal with two cardinals, I asked if they would celebrate a Mass in Carol’s memory. They said yes. A soft-spoken but powerful Catholic sister from a small city in Illinois would now be honored by some of the most powerful men in the church in Rome.

When I returned home, I emailed Carol’s nephew to let him know about the Masses. He thanked me, writing how much it meant to him and his family knowing that Carol would be remembered in this way.

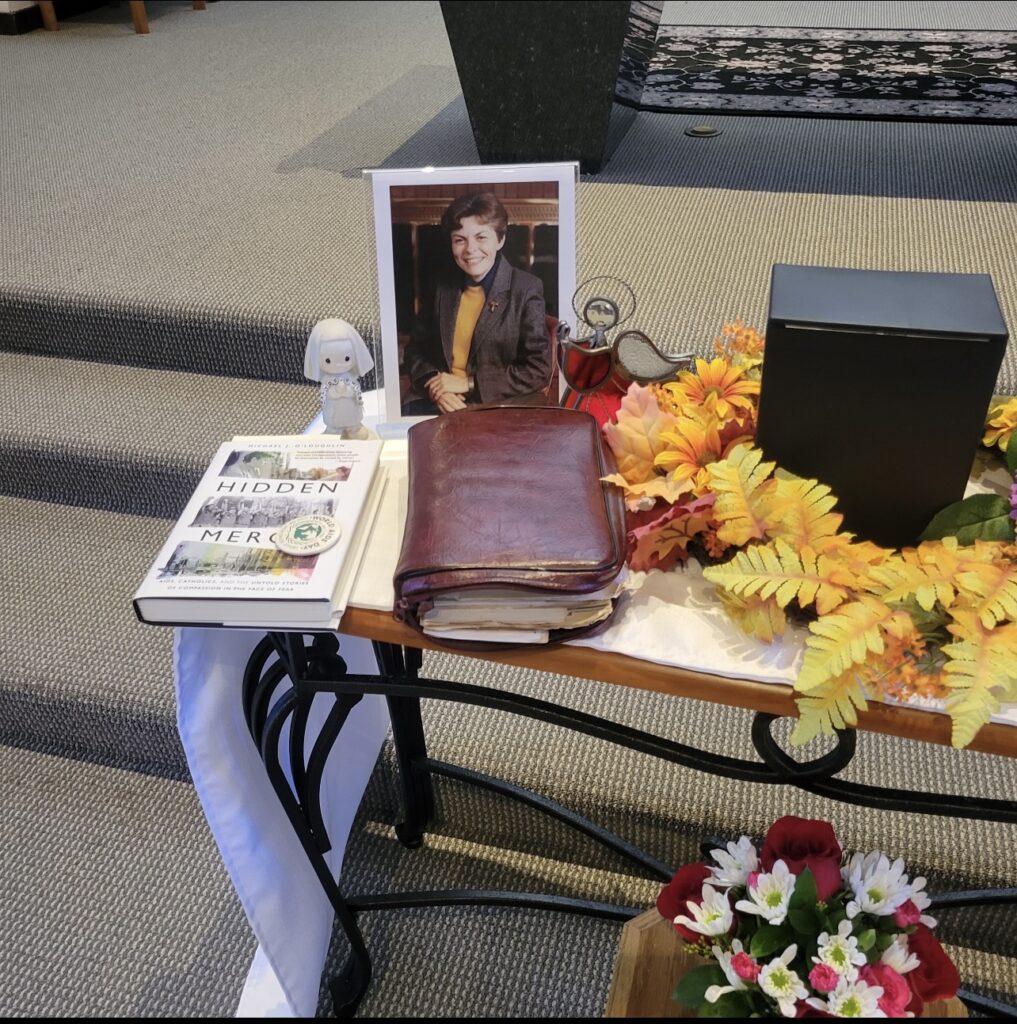

He also sent a photo of a small table that had been on display at Carol’s memorial Mass. On the table sat several objects: a photo of Carol, younger than when I met her but wearing the same smile that greeted me. A bouquet of flowers. A journal and a cross of St. Francis, an homage to the religious order she had joined as a young woman.

Then something else caught my eye. Tucked on the side of the table sat a copy of Hidden Mercy. Carol had certainly edified me in my own journey of reconciling my life with the church. And through the book, Carol had also inspired countless others as well, as evidenced by the many emails and messages I have received over the past few years.

A soft-spoken but powerful Catholic sister from a small city in Illinois would now be honored by some of the most powerful men in the church in Rome.

“I think of her often lately and try to place where she was in her life when I was reaching adulthood,” her nephew wrote to me. “We knew roughly what she was doing, and where she was, but didn’t realize the scope and the importance until we read your book. She talked about her work some, but clearly kept much of it to herself.”

“My family and I are so appreciative of the work you did to tell her story,” he wrote. “She did so much good, for so long, and so many.”

The image of Carol’s aged hand gently pressing the pages of her worn photo album remains with me. I felt in that moment that I was being given a glimpse of the tenderness that she had shown to the many young men whom she accompanied in their final days, of the tenacity with which she fought prejudice and even of the heaviness that seemed to stay with her in the years following her ministry.

With Carol’s departure from this life also go many of the memories she held of the lives cut short by a deadly disease, of her compassion and mercy that offered so many a moment of dignity during their darkest hours. I feel fortunate that before Carol’s death, I was able to capture a handful of these stories and put them down on paper. Perhaps others will pause, rest their hands on my pages, and reflect on the memories not only of the individuals Carol served, but pause to remember her unique and inspiring story as well.