Every time an LGBTQ Catholic or ally shares their story, the church must grapple with the experiences of flesh and blood people, not just the stereotypes and caricatures that dominate traditionalist ideologies. For this reason, over the course of more than a half-century, LGBTQ Catholic ministers have prioritized queer storytelling and autobiography as a way of transforming the church.

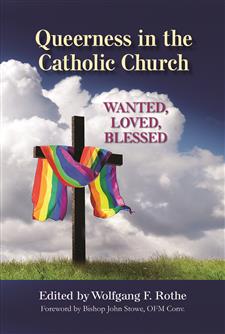

Recently, for example, New Ways Ministry published Love Tenderly: Sacred Stories of Lesbian and Queer Religious. And Paulist Press has released Queerness in the Catholic Church: Wanted, Loved, Blessed, a translation of 66 one- to two-page personal accounts edited by the Rev. Wolfgang F. Rothe, a Munich priest and doctor of canon law and theology. (The anthology was translated by Patrick Conlin, a doctoral student in theology at Marquette University.)

The tome, originally published in German in 2022, brings LGBTQ and allied experiences to an English-speaking audience. It features a foreword by Bishop John Stowe of Lexington, Ky., surely one of the most LGBTQ-affirming bishops in the United States. He frames the collection in light of the Synod on Synodality, which has encouraged the church to listen to the “entire People of God,” including those who have been “condemned, ignored, shamed, ridiculed, excluded, and even deemed nonexistent.”

LGBTQ Catholic ministers have prioritized queer storytelling and autobiography as a way of transforming the church.

The stories of LGBTQ people, the bishop explains, invite readers “into the sacred space of the lived experience of other members of the Body of Christ,” thereby contributing to an ecclesial culture of listening, encounter and relationship building. Bishop Stowe’s foreword reminds us that amplifying queer voices goes to the heart of the church’s mission.

In his introduction, Father Rothe offers a piercing look at the relationship between LGBTQ people and the church. This relationship, he says, “is always shaped by fractions, rejections, or tensions and therefore leaves [LGBTQ people] with injuries, hurts, and sorrows.” He is refreshingly open in his criticism of church teaching, arguing that queer suffering is “caused, namely, by a sexual morality based on assumptions and assertions that often have little to do with reality.”

The purpose of this book is to show us the realities of LGBTQ lives. Father Rothe brings LGBTQ people into the Catholic conversations about them, trusting that their stories will shake up the status quo and point the church in new directions.

He reminds us that the collection to come is as “colorful as it is complex.” Some LGBTQ Catholics have been able to reconcile their faith with their gender identity and sexuality; others have not. Some authors are comfortable enough to identify by their real names, while others remain anonymous. For the most part, participant diversity reflects the gendered and age dynamics that shape LGBTQ ministry more broadly.

Bishop John Stowe’s foreword reminds us that amplifying queer voices goes to the heart of the church’s mission.

Father Rothe admits, for example, that it was a challenge to find nonbinary, female and elderly people to share their stories. In the end, however, he sees the collection as a “pastoral project” that reveals the humanity of its queer and queer-friendly authors. This is the humanity that calls the church to be more Christian and Catholic—that is, more affirming—in its understanding of sexual morality and LGBTQ lives.

As I read Queerness in the Catholic Church, I was struck by the book’s simplicity. The vignettes are short but moving reflections on the good, bad and ugly in Catholic traditions and communities.

For LGBTQ Catholics and allies, the chapters may be familiar and remind us of our own experiences. Each vignette offers an evocative title, the author’s name (if provided), year of birth and work, giving us a brief glimpse into the storytellers’ backgrounds.

In spite of Father Rothe’s disclaimer, I was impressed by the diversity of ages, gender identities, vocations and relationships to Catholicism. Included are a wide variety of testimonies from people affected by the Catholic Church, including non-believers and those who have embraced Protestantism. Some authors have formal theological training, but most do not. Many continue to struggle.

This is a refreshing editorial decision that reflects the need for Catholics to listen to everyone, not just LGBTQ people who are comfortable in their relationship with the church and its traditions.

The book’s incarnational, Catholic approach leads us out of ignorance and exclusion to the queer peripheries where everyone is welcome and heard.

As theologians Marcella Althaus-Reid and Lisa Isherwood note, queer theology challenges us to discover God’s work in unexpected places, where accepted binaries and dogmatic certainties break down. This is especially true when we reflect on LGBTQ autobiographies, sources of theology historically disregarded by the institutional church.

Queerness in the Catholic Church encourages us to do just that. The book obliterates traditional boundaries between those who are in the church and those outside of it; between LGBTQ people and their allies; between “acceptable” and “unacceptable” forms of love; between the culturally-shaped markers for male and female; between heaven and earth. The book’s incarnational, Catholic approach leads us out of ignorance and exclusion to the queer peripheries where everyone is welcome and heard.