Winner of a 2024 Catholic Media Award

It took three days for Jackie to arrive in Kenya with nothing but the clothes on her back. A 28-year-old Ugandan woman, she escaped from her native country this August after her 1-year-old daughter, the product of a rape, was killed by one of her family members. Her family members thought that if they killed her infant daughter, Jackie explains, then she would “stop being a lesbian” and marry a man. Previously, she had refused to marry her rapist—despite the pleas of her family.

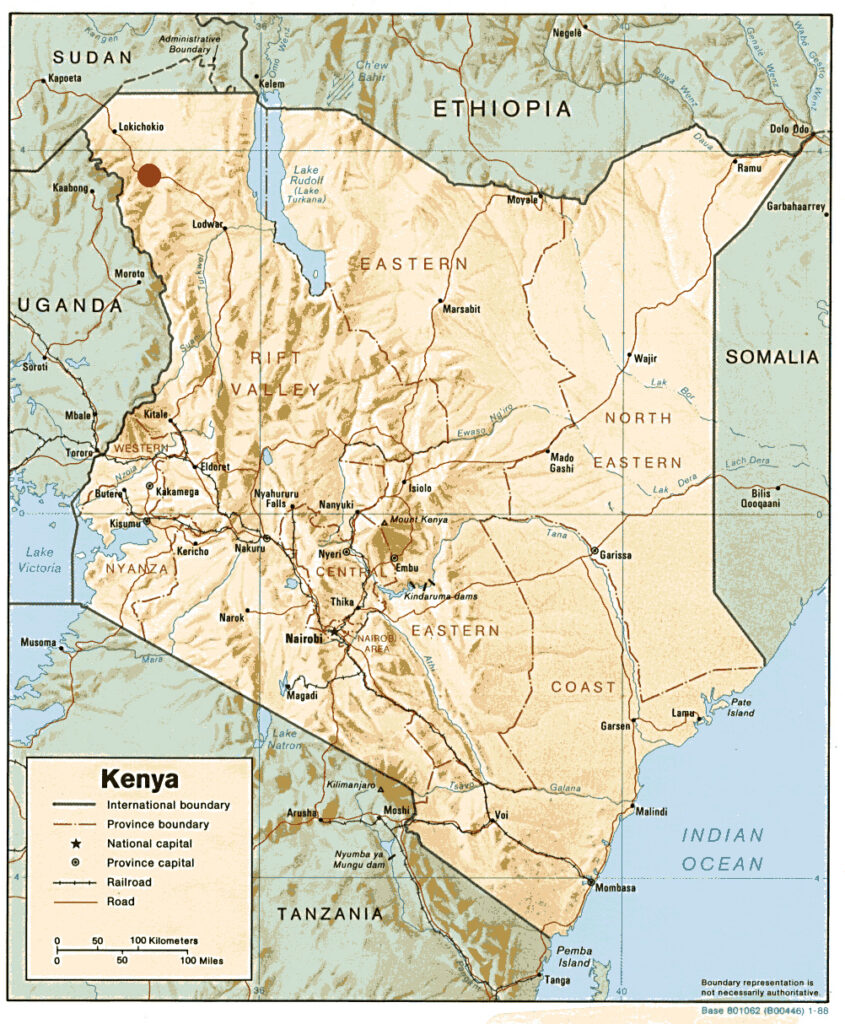

Desperate and isolated, she fled Uganda for the Kakuma refugee camp, a sprawling settlement in northwest Kenya first established to host Sudanese and Ethiopian asylum seekers in 1992. (Full disclosure: Outreach provided some financial assistance to help Jackie reach the refugee camp.) It is a desert camp that shelters more than 200,000 refugees and one of the largest refugee camps in the world, populated by asylum seekers from many countries, including Somalia, Burundi, Rwanda, Eritrea and the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

By the time Jackie got to Kakuma, her situation was just as dire, if not worse. She had no money for basic necessities, including sanitary pads. In early September, she was sickened by the camp’s harsh conditions, unclean water and poor quality food. A health clinic informed her that she was suffering from typhoid fever and malaria, common ailments among the refugees.

But there’s another kind of sickness spreading unchecked throughout the camp: a violent prejudice against LGBTQ refugees seeking asylum from their former homes. And as Jackie told Outreach, she and her LGBTQ friends face rejection even among other refugees at Kakuma. “They don’t like us here,” she said.

Jackie’s story is similar to those of many young LGBTQ Ugandans who, having faced discrimination and violence in their native country, escaped to Kenya only to fight for their lives. In speaking regularly with several Ugandan refugees at the Kakuma camp over the last five months, Outreach has learned through more than a dozen interviews about repeated arrests, frequent violence, food shortages, outbreaks of malaria and typhoid, inadequate shelter and persistent discrimination facing LGBTQ people—many of whom have been stranded in Kenya for years.

And despite oversight from the U.N. Refugee Agency (U.N.H.C.R.), which has grappled with an extreme budget shortfall in 2023, and the dedicated work of humanitarian groups like Amnesty International and the Jesuit Refugee Service, displaced LGBTQ persons have expressed their ongoing frustrations with aid groups they say have failed to provide substantial assistance. However, the U.N.H.C.R. has reiterated its support for LGBTQ refugees, and in a December statement to Outreach, noted “a significant decline” in violent incidents over the past few months.

Meanwhile, the Catholic Church in Africa has said little on this growing crisis, and conservative U.S. Christian groups have spent years in Uganda promoting an anti-homosexuality agenda.

A history of violence and intolerance

The refugees have come to Kakuma amid state-sanctioned persecution in Uganda, where same-sex relations are illegal and a new anti-LGBTQ bill has put their lives at risk. President Yoweri Museveni, who has ruled Uganda since 1986, approved in May a draconian law seeking to suppress homosexuality by threatening sexually active LGBTQ people with life imprisonment and, in some cases, death. In August, the country accused a 20-year-old man of “aggravated homosexuality,” a charge that carries the death penalty.

In August, Uganda accused a 20-year-old man of “aggravated homosexuality,” a charge that carries the death penalty.

The law has been met with international condemnation, particularly in the West. Shortly after its enactment, the United States restricted travel visas for several Ugandan officials, and in October, numerous federal departments issued a warning to businesses working within the country. “The enactment of Uganda’s Anti-Homosexuality Act is a tragic violation of universal human rights—one that is not worthy of the Ugandan people, and one that jeopardizes the prospects of critical economic growth for the entire country,” wrote President Joe Biden in May.

This month, the White House reiterated its support of LGBTQ rights in Uganda while the State Department widened its sanctions on current and former Ugandan officials who target, in any way, other marginalized groups, including climate activists, reporters and human rights advocates.

This is not the first time Uganda’s repressive posture toward LGBTQ people has drawn ire from the U.S. and its allies. In 2014, Uganda enacted a separate law criminalizing same-sex relations and the promotion of homosexuality. Under that law, landlords faced up to five years in prison for renting to an LGBTQ person and not alerting the police.

The international response was swift: The U.S. sanctioned Uganda while European nations— including Denmark, Norway, the Netherlands and Sweden—halted aid programs. The World Bank announced it would withhold a $90 million loan to the country until the law was eventually reversed. And in August 2014, a Ugandan court overturned it.

In an interview with Outreach, Scott H. DeLisi, who served as the U.S. ambassador to Uganda during the Obama administration, said that the passage of the 2014 bill was met with both outrage and surprise. Ambassador DeLisi said there was “a reasonable expectation” that the bill would not pass because, both before and during his ambassadorship, the United States was engaged in dialogue with Uganda on LGBTQ human rights.

Nevertheless, President Museveni made headlines in 2014 when he called gay people “disgusting” and characterized homosexuality as a choice. “What sort of people are they?” he asked a CNN reporter. “I’ve been told recently that what they do is terrible.”

Ambassador Scott H. DeLisi: “Absolutely, President Obama’s administration was very clear on their concerns about this [2014] legislation. The challenge then became, ‘What do you do about it?’”

DeLisi described a tense environment in Washington where focus shifted to how the United States should respond to the anti-LGBTQ bill. “Absolutely, President Obama’s administration was very clear on their concerns about this legislation. The challenge then became, ‘What do you do about it?’”

The U.S. faced a need to confront human rights violations in Uganda while not alienating an ally in both counterterrorism efforts and the global fight against AIDS. “We were determined to stand for something,” said DeLisi. “It really brought home to us this debate both about values and interests, [about] the importance of finding an alignment of values with your host nation.”

Perhaps the most prominent international advocate for gay rights in Uganda, Frank Mugisha, the executive director of Sexual Minorities Uganda, has emerged as an unofficial envoy for Western leaders concerned with LGBTQ protections in Africa and beyond. Mugisha, a distinguished fellow at Columbia University’s Institute of Global Politics who met with former Secretary of State Hillary Clinton in October, is currently challenging the most recent anti-gay bill in Uganda’s Constitutional Court.

In an interview with Outreach, he described an environment of violence and “increasing hostility” toward LGBTQ people even before the law was passed. And he accused Ugandan law enforcement of extorting and blackmailing LGBTQ people after they were arrested. (A 2013 report, the conclusion of a “fact finding mission” with the Danish Immigration Service and the Danish Refugee Council, includes numerous allegations of the extortion of LGBTQ people by Ugandan police.)

What church leaders have (and haven’t) said

Mugisha also remarked that some church leaders have embraced the new bill. “Many of the religious leaders in Uganda support this legislation,” he said to Outreach. But he explained that while the Catholic Church in Africa is vocal against same-sex marriage and sexual relations, they have not issued statements in support of the death penalty for LGBTQ people.

In a landmark interview with The Associated Press this January, Pope Francis became the first pontiff to call for the worldwide decriminalization of homosexuality—a major statement challenging global church leaders, especially in Africa, to confront and reject laws in their countries that seek to imprison LGBTQ people. “Being homosexual isn’t a crime,” said Francis, calling Catholic bishops to “conversion” on this topic. “We are all children of God.” The pope later reiterated his comments in a letter to Outreach: “I wanted to clarify that it is not a crime, in order to stress that criminalization is neither good nor just.”

Frank Mugisha: “Many of the religious leaders in Uganda support this legislation.”

But the Rev. Kapya Kaoma, an Anglican pastor from Zambia who now serves at Christ Episcopal Church in Waltham, Mass., said that Pope Francis “betrayed the LGBTQ community in Africa” by not mentioning decriminalization or human rights violations against the gay community when the pope traveled to Uganda in 2015. “Pope Francis had an opportunity to make a difference when he visited Uganda (or Africa as a whole), but he didn’t mention a word about homosexuality. Neither did he even have a chance to meet with LGBT people in Africa.”

When asked why Catholic bishops in Uganda had not responded to the pope’s call for decriminalization, Reverend Kaoma said it was because the pope’s message was not specifically directed toward a bishop or diocese. “[The pope’s call] is more of what I consider to be a general political statement which has no focus,” he said. Still, he described his “great respect” for Francis; a book of the pope’s homilies sat on the pastor’s desk during our interview.

Watch Reverend Kaoma, interviewed in his Massachusetts office this May, describe how the lives of LGBTQ Africans hinge on the advocacy of Pope Francis:

Writing in opposition to the 2014 anti-homosexuality bill, the editors of America magazine stated that the church’s defense of marriage must be coupled with a defense of LGBTQ human rights. “The church must oppose violence against gay persons and should strongly advocate for the decriminalization of homosexuality,” reads the editorial. And in June 2015, the Rev. Anthony Musaala remarked that LGBTQ Ugandans had begun escaping to Kenya to avoid rape, eviction and the loss of employment.

Earlier this month, Cardinal Peter Turkson, a Ghanaian prelate whose native country is moving to make homosexuality illegal, publicly opposed efforts to criminalize LGBTQ relationships and demonstrated support for the pope’s priorities. The cardinal instead called for people to educate themselves about the “phenomenon” of homosexuality in order to increase understanding.

Joseph Loïc Mben, S.J., a Catholic priest and bioethicist from Cameroon, told La Croix International in February that criminalizing homosexuality in Africa is a kind of “one upmanship” among politicians who have not sufficiently addressed serious social problems, like poverty, in their countries. Referencing the pastoral style of Pope Francis, Father Mben called LGBTQ people “children of God.”

During a homily this February, Bishop Sanctus Lino Wanok of Lira, Uganda, called homosexuality a “death, which humanity must repent against.”

Still, Catholic prelates in Uganda (and throughout Africa) have remained mostly silent on the persecution of LGBTQ persons and the pope’s push for decriminalization, while some have actively supported discriminatory practices. “African Roman Catholic bishops and cardinals are the ones who are campaigning for these bills,” said Reverend Kaoma.

During a homily this February, Bishop Sanctus Lino Wanok of Lira, Uganda, called homosexuality a “death, which humanity must repent against.” And in September 2022, Archbishop Alick Banda of Lusaka, Zambia, who Reverend Kaoma specifically mentioned to Outreach, quoted the Sermon on the Mount to preach that Catholics must oppose the “proliferation” of homosexuality—a sign of “moral degeneration”—in his country.

This June, Juan Carlos Cruz, a Chilean-born member of the Vatican’s Pontifical Commission for the Protection of Minors (and a keynote speaker at the 2023 Outreach conference), urged Ugandan bishops to defend LGBTQ people against the current anti-homosexuality bill. He specifically noted that nearly 40 percent of the Ugandan population is Roman Catholic, the country’s largest Christian group.

“While the international outcry grows louder,” writes Cruz in the National Catholic Reporter, “the silence from a significant portion of Uganda’s moral and spiritual guardians—the Catholic bishops—is deafening.” Numerous Catholic bishops in Uganda did not respond to requests for comment from Outreach.

A scholar of religion and sexuality in modern Africa, and the author of Kenyan, Christian, Queer, Adriaan van Klinken has found that Christianity in Africa is not just a source of homophobia, but a catalyst for queer activism and expression. Speaking this month with Outreach, Dr. van Klinken, who was raised in the Netherlands and visited Kenya in 2015, noted that there are numerous Christian denominations throughout the country, as opposed to Uganda, where the Anglican Church remains the major religious force.

Van Klinken described a “symbiotic relationship” between the “fragmented” Kenyan church and the government, both united in opposition to homosexuality, which stems historically from colonialist prohibitions on same-sex relations.

But he states that modern-day African condemnations of homosexuality harken back to the former Zimbabwean president Robert Mugabe, an authoritarian leader who in 1995 described gay and lesbian people as “dogs and pigs.” Into the new millennium, as gay rights became more recognized in the United States, van Klinken described a shift in Africa where the persecution of LGBTQ people increased.

But in a country like Kenya, where Christian symbols and practices are cultural hallmarks, many LGBTQ people have grown up with religion, and then realizing and potentially embracing their identity, have found creative ways of interpreting their faith.

“Coming out or embracing your queer identity, your sexuality, doesn’t automatically mean that you give up on your faith [in Kenya],” said van Klinken. And research proves it: In a 2019 article from the journal Politics and Religion, the authors found that interactions with a diversity of religions in Africa was likely to “engender tolerance towards marginalized communities.”

In early September, Nina—a 24-year-old transgender woman who arrived at Kakuma in February 2020—and her partner Davie were wearing rainbow bracelets when they were arrested by the Kenyan police. They were beaten with batons and had their dreadlocks forcibly cut. When Davie tried to resist, they beat him further, leaving dark welts on his back, which Outreach saw on a Zoom call right after his release from jail. “They’re trying to keep us silent,” said Nina. “They want to arrest every [LGBTQ] person that raises awareness or talks about our situation on social media.”

It was Nina, then known as Ray, who first contacted Outreach in July about the deteriorating situation at Kakuma. She has been vocal on social media about spreading awareness of the situation for LGBTQ people inside the camp—and her activism has made her a target. She said she travels in a group with other transgender people in order to survive and that aid organizations have not helped.

“Even if we go to the U.N.H.C.R. or J.R.S. [the Jesuit Refugee Service], they don’t listen. They said, ‘If you want to live in Kakuma, you have to stop being transgender in public.’ We are voiceless,” said Nina.

Budget cuts, food shortages and police attacks

Geoffrey Shikuku, the country director for Kenya at the Jesuit Refugee Service, explained that the camp is managed by the U.N.H.C.R. and the Kenyan police under the country’s Department of Refugee Services (D.R.S.). Steve Oten, the J.R.S. project director for Kakuma, described “a general decline in the economic situation and food rations for refugees in the camp” due to budget cuts by the World Food Programme and the arrival of more than 24,000 refugees from South Sudan.

In an extensive 54-page report published this year by Amnesty International, the organization detailed hate crimes and instances of discrimination against LGBTQ refugees in Kenya. The report describes the persistent harassment of LGBTQ refugees by Kenyan law enforcement, a lack of options for third-country resettlement so refugees could leave Kakuma, homophobic threats and assaults from people inside the camp, and a “systematic and pervasive failure” among government officials to safeguard LGBTQ lives.

Akin to what LGBTQ refugees have told Outreach, the stories contained in the report are horrific: a 41-year-old lesbian woman twice raped inside the camp, another lesbian woman attacked with sticks and stones, a gay man locked in a room and beaten with a cane by six “subcontracted security officers.” Isabel, a transgender woman, informed investigators that Kenyan police told her and four other activists in May 2021 to “stop sharing evidence of violence” against LGBTQ refugees in the camp.

The report comes to a startling conclusion: Both Amnesty International and the National Gay & Lesbian Human Rights Commission say that Kakuma “is not safe for LGBTI asylum seekers and refugees.”

On March 15, 2021, a group of Kakuma refugees approached makeshift shelters for LGBTQ refugees while they were sleeping. Using water bottles filled with petrol, the attackers set fire to numerous settlements and then tossed the gasoline onto the refugees themselves, creating what one refugee interviewed called “a petrol bomb.” Two people were severely burned in the attack. One person survived, the other did not. “We are deeply shocked by this tragic loss and wish to express our sincere condolences to the family and friends of the victim,” said a U.N. representative at the time.

Victor Nyamori, the regional refugee coordinator at Amnesty International’s East Africa office, in Nairobi, referenced the 2023 report. “We have documented instances of discrimination [among LGBTQ refugees] in access to services, from the community itself but also from the NGOs that support refugees in the camp,” he said in an interview with Outreach.

Nyamori explained that most people in the camp believe that all Ugandan refugees, easily identifiable as they speak English, are LGBTQ—making them a visible target. He also noted that law enforcement and camp officials are aware of LGBTQ refugees facing obstacles to food and water distribution, but are taking little to no action to address the problems.

The LGBTQ refugees interviewed by Outreach were all critical of the U.N.H.C.R., bluntly stating they feel that the U.N. does not care about them. And the refugees’ efforts to reach U.N. officials at their Kakuma offices (what the refugees call “the compound”), have proven difficult. In a statement to Outreach this month, the U.N.H.C.R. said it organizes “periodic meetings” with the LGBTQ refugees, but “cannot be as responsive or timely as we would like” due to the presence of nearly 700,000 refugees throughout Kenya.

U.N.H.C.R.: LGBTQ refugees in the camp “face challenges in their daily lives as a result of discrimination and intolerance.”

The U.N.H.C.R. acknowledged that LGBTQ refugees in the camp “face challenges in their daily lives as a result of discrimination and intolerance,” but affirmed that the agency continues to work with the Kenyan government to safeguard their lives.

However, the agency claimed it was unaware of any refugees being arrested “without due cause,” despite Amnesty International’s extensive documentation of harassment by Kenyan police. Further, the agency stated that many refugees have waited decades in the camp for resettlement to another country—but that they shouldn’t necessarily expect it.

“Contrary to what many believe, resettlement is not an automatic right available to all refugees. …In fact, each year less than half of one percent of the world’s refugees are able to benefit from this solution,” reads the U.N.H.C.R. statement.

In late April 2020, the U.N. Refugee Agency detailed its “concern about a sit-in” at the compound, where some 60 refugees sought resettlement outside Kenya. The agency, in a press release, discouraged refugees from gathering in groups due to the spread of Covid-19 but added that it “support[ed] the right of refugees to peaceful and lawful protest.” After three days, the National Police Service tear gassed protestors outside the compound and injured 11 refugees.

Two refugees who spoke with Outreach claimed that a second sit-in protest took place outside the compound this March. When some 300 protestors, according to Nina’s estimate, arrived outside the U.N. building, the Kenyan police again violently dispersed the crowd. “They tear gassed us and beat us terribly,” said Aisha, a lesbian refugee. “We slept in the police cells.” In their statement to Outreach, the U.N.H.C.R. alluded to refugee-led protests this year, but denied using tear gas and warned about the “spreading of false information.”

The U.N. Refugee Agency is struggling from a severe budget shortfall, with a little more than 30 percent of its nearly $11 billion budget secured by the end this year.

“One issue that [Amnesty International] has had with the U.N.H.C.R. is instances where victims are being blamed for circumstances that transpired, especially within the LGBTI community,” said Nyamori. (“LGBTI” is the abbreviation most often used among Ugandan activists and African leaders.) He said that the U.N. has arranged several “engagements” with LGBTQ refugees in the camp, “but I won’t say that it’s enough.”

Amnesty International and the J.R.S. also remarked that the U.N. Refugee Agency is struggling from a severe budget shortfall, with a little more than 30 percent of its nearly $11 billion budget secured by the end this year. The agency, which met nearly 60 percent of its budget last year, is projecting a $1 billion shortfall for 2023, and in July warned that it could be “forced to reduce or cut critical programming.”

Shikuku called it “unusual” that the agency had secured less than 25 percent of its budget in the year’s first quarter. “[The U.N.] has been doing what we call ‘deprioritization,’ so that what you have already prioritized you have to de-prioritize because of the available resources,” Shikuku said.

“U.N.H.C.R., like many U.N. agencies, faces the implications of under-funding caused by mounting global displacement and other crises and diminishing humanitarian budgets, which are widening the gap between available resources and needs,” explained the agency in their statement to Outreach.

Godwin is sitting in a Kakuma shelter one November morning as blinding sunlight breaks through the patterned curtains suspended around him, the daytime brightness completely shadowing his face. He fled Uganda for the camp in March 2021; in his native country, he was an LGBTQ activist who found work as a medical assistant in local hospitals. After he was met with allegations of promoting homosexuality, he went on the run.

But he hasn’t found much support in the camp. In fact, he says, Kakuma officials do not understand the LGBTQ community, leaving them isolated. “This is why everyone [in the camp] has turned into an activist, to raise and amplify their voices so that we all cannot perish in the camp,” he told Outreach. “Our survival depends on supporting each other—friends supporting each other—so that we don’t die.”

“Is the situation in the camp really any better than the situation you faced in Uganda?” we asked. “The situation here in the camp is worse,” he said. “It is worse.”

Some two weeks after our interview, Godwin was arrested by the Kenyan police.

Homosexuality in Africa—and beyond

Persecution, violence and legal repercussions against LGBTQ people extend beyond Uganda and throughout the continent, where the majority of countries criminalize same-sex relations. Uganda, Nigeria, Mauritania and reportedly Somalia, specifically in areas controlled by the Sunni militant group Al Shabab, maintain the death penalty for homosexuality, according to research from the Council on Foreign Relations. Nearly half of Africa prohibits gender-affirming care for transgender and non-binary individuals.

Uganda, Nigeria, Mauritania and reportedly Somalia, specifically in areas controlled by the Sunni militant group Al Shabab, maintain the death penalty for homosexuality.

But the criminalization of homosexuality and the persecution of LGBTQ people is not distinct to African countries. The Human Dignity Trust, a London-based nonprofit that opposes criminalization efforts, cites 12 countries, including eight non-African countries mostly concentrated in the Middle East, that impose or may impose the death penalty for gay sex between consenting adults. Sixty-five jurisdictions criminalize homosexual behavior.

However, same-sex relations between consenting adults are legal in 23 African states—that is, more than 42 percent of all African countries—according to the I.L.G.A. World Database, an LGBTQ human rights group. Hover over Outreach’s interactive map below for current data on the criminalization of homosexual acts in Africa.

In an article for Outreach, Ram Gava, an LGBTQ-inclusive Christian pastor in Kampala, characterized all of East Africa as unsafe for gay people. “In our region, severe discrimination is common and often results in torture, persection and social stigma,” wrote Gava last May. “LGBTQ people live a life of hiding, even from their own families, because once they come out … they are disowned and abandoned.”

Kenyan legislators have begun talks aimed at criminalizing “everything to do with homosexuality,” as one politician put it. A proposed bill imposes a maximum 50-year prison sentence specifically for “non-consensual same-sex acts,” according to Africa News. But in February, the country’s Supreme Court ruled that discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation is unconstitutional, a major win for LGBTQ activists that led to nationwide protests and created a “moral panic.” Meanwhile, the Kenyan politician Mohamed Ali opposed LGBTQ relationships as violating the religious values of his county. “Islam and Christianity are against ‘gayism,'” he said.

Russell Pollitt, S.J., the director of the Jesuit Institute South Africa, wrote for Outreach in November 2022 that LGBTQ people still face hazardous conditions in his country, even after its 1994 constitution was the first in the world to outlaw discrimination against LGBTQ people and same-sex unions were legalized in 2006.

Kenyan legislators have begun talks aimed at criminalizing “everything to do with homosexuality,” as one politician put it.

“There’s a big gulf between the law and its application,” he said in an interview with Outreach this year. “We’re dealing with a pretty conservative evangelical kind of Christianity here in South Africa.” Father Pollitt remarked that a patriarchal culture, extant in South Africa and throughout the continent, makes the country dangerous for LGBTQ people and women.

Additionally, homosexuality remains a highly taboo topic, contributing to a climate of misunderstanding and fear. “Although [LGBTQ people] may be protected by law,” wrote Father Pollitt, “they still find themselves stigmatized and, at times, attacked in local communities.” He compared this “inhospitable” environment to the Democratic Republic of the Congo, where homosexuality is legal but LGBTQ people are still physically attacked.

Just this month, Catholic bishops in Zambia, Malawi and Nigeria—all countries where homosexuality is illegal—issued statements defying a major Vatican declaration that now allows priests to bless same-sex couples. Zambian bishops moved to prohibit blessings for same-sex couples due to that country’s laws and “to avoid pastoral confusion.”

Wearing a teal V-neck shirt, Fahad spoke to Outreach via Zoom while seated on the ground, his back leaned up against a makeshift shelter. A 24-year-old Ugandan man, he said he was brought to Kakuma through the Kenya Red Cross Society in March 2020. He told us that in addition to living under persecution in the camp, LGBTQ refugees live without basic necessities for themselves or their children.

“Life is really a total misery for almost all of us in the camp,” says Fahad as a rooster’s crow punctuates the air. He begins to count the dead: maybe five or six LGBTQ people in three and a half years. “We’ve lost colleagues, friends and babies during the struggle,” he says. He covers his face and begins to cry. Another crow.

U.S. evangelicalism in Uganda

Victor Mukasa, a Ugandan-born LGBTQ human rights activist, was raised in a “staunch Catholic family,” but he fled Africa for Baltimore in 2012. “When the U.S. evangelicals came in, a lot of things changed,” said Mukasa in an interview with Outreach. “They created an environment of homophobia that I could not continue to thrive in with my children.”

Beginning in the early 2000s, the born-again Christian activist Scott Lively, a native of Massachusetts who had spent decades preaching “the dangers of homosexuality” and calling it a “personality disorder,” began speaking in Uganda (and was invited to address the Ugandan parliament alongside other anti-gay U.S. evangelicals) to denounce the evils of homosexuality.

Lively first arrived in Uganda in 2002 and continued his anti-LGBTQ activities there up through at least 2009, when the country’s parliament introduced a bill to punish LGBTQ people with possible life imprisonment and impose the death penalty in some situations. The Washington Post reported that Lively, in his address to the Ugandan parliament, characterized homosexuality as a Western “disease” that had arrived in Africa to corrupt children.

Lively was not alone in his efforts: In 2010, Lou Engle, an American evangelical leader known for organizing prayer rallies back home, addressed some 1,300 people at Makerere University in Kampala. Engle, who in 2008 referred to homosexuality as “a spirit of lawlessness” and once called on his followers to fast so that 100,000 gay and lesbian people would be “radically transformed,” had come to oppose the 2009 bill as too cruel, but he arrived in Africa to speak at an event mainly about homosexuality, political corruption and witchcraft.

In March 2009, Caleb Lee Brundidge, an “ex-gay” Christian leader who styled himself as a “sexual reorientation coach,” also participated in a three-day seminar condemning homosexuality in the Ugandan capital.

(The 2013 documentary “God Loves Uganda” details the strong ties between the Ugandan government and U.S. evangelicalism. Lively, Engle and Brundidge did not respond to requests for comment from Outreach.)

Mukasa explained that U.S. evangelicals organized these meetings to convince church leaders that LGBTQ people were “sodomizing children” throughout Uganda and attempting to “recruit” Africans into homosexuality. He witnessed a change in African pastors’ rhetoric, shifting from quoting Leviticus to naming LGBTQ people as a threat to children. And he said the actions of these evangelical leaders led directly to the passage of the 2014 Anti-Homosexuality Act.

“The language in the bill was the very language that those U.S. evangelicals here in America were using, and the [evangelicals] who came to visit [Africa] had introduced to Uganda,” said Mukasa.

In October, Representative Tim Walberg, a Republican of Michigan, urged Ugandan leaders at the country’s National Prayer Breakfast to “stand firm” on its anti-homosexuality bill.

The New York Times noted that the 2009 bill placed a spotlight on American evangelicals and politicians who “offered themselves as experts on what they consider the scourge of homosexuality.” But why would these American-born preachers target lawmakers and pastors in Uganda? Now a resident of Baltimore for over a decade, Mukasa has observed that many Americans aren’t receptive to anti-LGBTQ propaganda from evangelical pastors—and so the pastors started looking elsewhere.

In Uganda, where homophobia was rampant far before 2009, they found their message well-received. “[The homophobia] was already there,” said Mukasa, “it’s just that the Americans came and put it at a different level.” And this U.S.-based advocacy continues today. In October, Representative Tim Walberg, a Republican of Michigan, urged Ugandan leaders at the country’s National Prayer Breakfast to “stand firm” on its anti-homosexuality bill. President Museveni was in the audience for Rep. Walberg’s keynote speech.

“Our hope is nowhere”

More than two dozen representatives of the LGBTQ community in Kakuma met inside the camp on December 19 with the members of the U.N.H.C.R., the Department of Refugee Services (D.R.S.), World Vision (a U.K.-based humanitarian group), the World Food Programme and the Danish Refugee Council. In a wide-ranging conversation, the participating members discussed options for third-country resettlement, refugees status determination and the possibility of private sponsorships allowing LGBTQ refugees to leave Kakuma.

LGBTQ refugees in Kenya: “Our hope is nowhere, we are doomed and the only option we have right now is suicide.”

But in a document obtained by Outreach and written by five refugees who attended the meeting, the LGBTQ asylum seekers expressed strong disappointment in meeting and stated that even private sponsorship organizations take too long to help. In its statement to Outreach, the U.N.H.C.R. wrote that solutions for the refugees’ problems are largely the responsibility of the Kenyan government, and the agency noted that the meeting “did not offer solutions to most of the challenges raised.”

The refugees’ summary of the meeting ends with a disturbing note: “Our hope is nowhere, we are doomed and the only option we have right now is suicide.” When asked about its response to the refugees’ apparent intent to harm themselves, the U.N.H.C.R. wrote it was “deeply concerned” and directed the refugees to counseling services.

“In the camps, U.N.H.C.R., D.R.S. and partners work closely with

communities to promote peaceful coexistence,” wrote the agency.

Finding family in a desert prison

Emmanuel, a 23-year-old gay man living in Kakuma, says he was completing high school when he fled from Uganda to the camp in February 2020. In late 2019, he was a closested teenager engaged in a secret relationship with another man, who lived in the same province as his uncle.

Rumors swirled around the community about Emmanuel and his partner. They were moving around together; they were seen hugging. After Emmanuel began coming home late at night, he was confronted by his uncle, who asked if Emmanuel was gay. Emmanuel said no. “I had to deny it in order to save my life,” he said.

After Emmanuel’s uncle called his parents with suspicions about their son’s homosexuality, he had no choice but to run. “My father wanted to kill me. He told me I should never step foot in his compound again,” said Emmanuel. Disowned by his family, he said he wandered the streets of Kampala homeless before fleeing toward Kenya in January 2020. “I never thought that I would be a refugee,” he said.

He lost contact with his former boyfriend and was later arrested in Nairobi without immigration papers. After two weeks, he was released from police custody. Later, he came into contact with the U.N.H.C.R. and was eventually transported to Kakuma. He hasn’t heard from his family since. “The family I have is the family that I have found in Kakuma,” he told Outreach.

“I never thought that I would be a refugee,” said Emmanuel.

Outreach asked Emmanuel to describe conditions at the camp today. He called Kakuma “a prison,” a place where people can be arrested, kidnapped or disappeared if caught running out of the camp. Some people who escape may travel to Nairobi to look for work, says Emmanuel, but for LGBTQ refugees now stranded in the sweltering Kenyan desert, there is simply nowhere else to go without significant help from private sponsors.

“You can die here and no one will ask about it,” said Emmanuel. “No one is trying to save you.”

Are you interested in supporting the refugees you met through this article? Please contact kalyowabuda@gmail.com or message Outreach at reachout@outreach.faith.

Updated Jan. 4, 4:35 p.m.