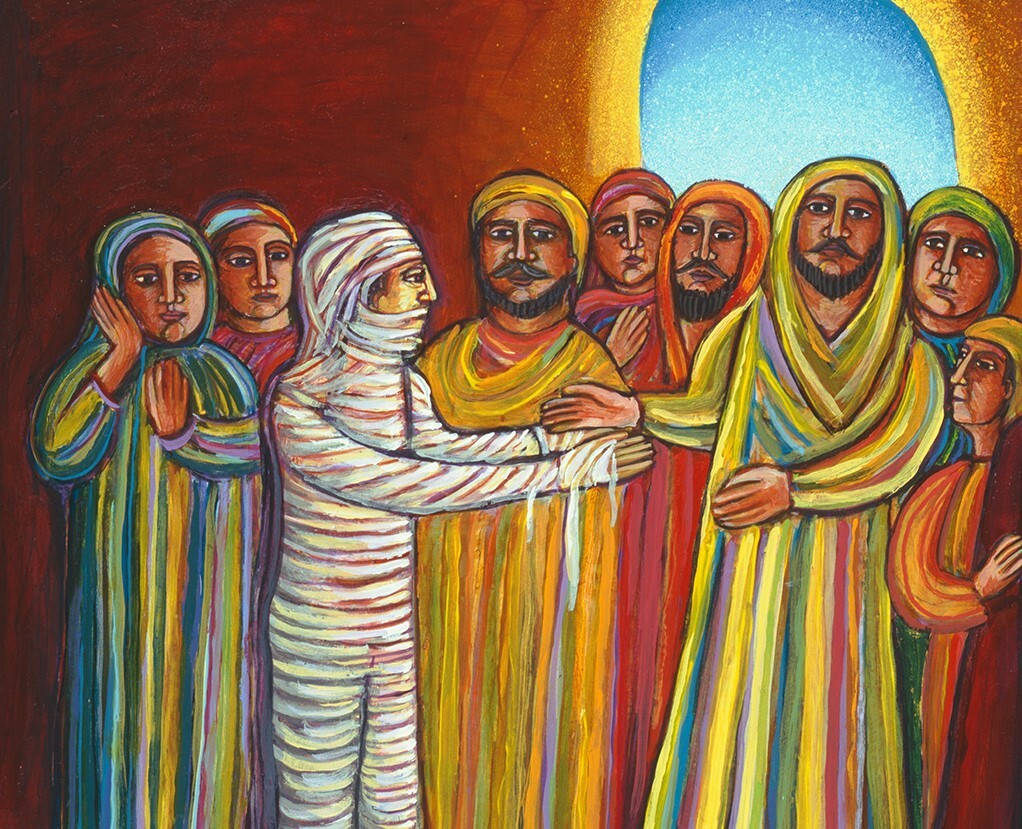

This essay is adapted from James Martin, S.J.’s new book Come Forth: The Promise of Jesus’s Greatest Miracle, available from HarperOne.

When Jesus arrives in Bethany, he asks the sisters of Lazarus, Martha and Mary, where their brother is buried (Jn 11: 1-44). Upon arriving, he says, “Take away the stone.” Martha, who has already professed her belief in Jesus as the Messiah, then says something odd, “There will be a stench.” Now, it’s not fair to fault Martha—even though Jesus had been known to raise people from the dead, how could she have known what was about to happen?

Nonetheless, she is, you could say, focusing on the negative.

Another way of approaching this part of our story is from an even earthier point of view: rotting flesh. That’s an unpleasant image to conjure up, but it is part of the story. Lazarus had a human body, had been ill for some time and after four days in the tomb, no matter what anointing had been done, his body would have started to decompose and to stink.

Sometimes we believe these parts of us are so rotten that God wouldn’t want to look at them either.

But let’s think about this more metaphorically.

My friend Michael Peppard is a Fordham University theology professor, who shared with me some of the scholarly conversations about Lazarus perhaps being the mysterious figure known as the “Beloved Disciple,” in John’s Gospel.

As I was writing this book, I attended Mass in New York City with Michael and his wife, Rebecca. At lunch afterwards, they asked about my writing, which led to a discussion about Lazarus. Rebecca said that she loved this story because there are some things in our lives that we think are “rotten” or “decaying.”

Something about what Rebecca said made me hear that part of the story in a new way. Throughout this book, we have talked about God calling us into new life, as Jesus called Lazarus. There are parts of us that we want to “let die” or “leave behind” in the tomb.

But Rebecca’s comment reminded me there are also parts of us that we see as “rotten.” Not exactly dead, but so awful that we can barely look at them: unpleasant, unsavory, disgusting, embarrassing, even shameful. Sometimes we believe these parts of us are so rotten that God wouldn’t want to look at them either.

God isn’t afraid of the “stench”

Some of us struggle with an addiction to drugs, pornography, gambling, sex, drinking, overeating. Or perhaps we are engaging in an unhealthy pattern of behavior that isn’t an addiction but still makes us feel disgusted with ourselves. Perhaps we can’t help saying mean things about people, or we’re always passing on the hard work to others in the office, or we can’t be bothered to visit friends who are in the hospital, or we occasionally cheat on tests, or we post nasty comments on social media. Even though the behavior makes us feel rotten, we can’t stop doing it.

Or maybe we feel we’ve done something in the past that is so horrible that we fear it can’t be forgiven. We can barely stand to think about it. Perhaps we were cruel to someone in our family or betrayed them. Perhaps we cheated on our spouse or partner. Perhaps we did something so awful that we’ve never told anyone about.

God is not afraid of the stench, just as Jesus was not afraid of the stench of Lazarus.

Part of us feels rotten, putrid, foul inside. There is, to quote Martha, a “stench.”

Like a person turning away from rotting flesh, we can barely stand to look at it, much less think about it. We want to keep the stone tightly shut over that part of us.

It is to this part of us that God calls. It is this part of our lives that God wants us to confront and to examine. More important, God wants to confront it with us.

But what exactly does that mean? In many cases, it means first admitting to ourselves that it is part of us and that it feels rotten. Then it may mean admitting it to a trusted friend, or a therapist or a spiritual director.

Then it may mean looking at how that part of us became so rotten. Something causes meat to rot—it’s taken out of the refrigerator, it’s exposed to air, it encounters bacteria or mold, which causes it to decay. A trusted friend, counselor or therapist can often help us see how that rottenness came about, help us to confront it, deal with it and then avoid it in the future. A priest may hear our confession and offer us forgiveness for whatever we might have done. Or we simply decide not to do it any longer. In all this, we hear God’s voice.

God is not afraid of the stench, just as Jesus was not afraid of the stench of Lazarus.

“I like you the way you are”

Sometimes the parts of us that we think are rotten are perfectly healthy, and it’s our way of looking at our rottenness that needs to be examined.

In my ministry with LGBTQ people, I sometimes meet people who believe they were created in a faulty way, that there is something deeply wrong with them, that they are “rotten.” Sometimes it takes years for them to realize that this part of themselves is healthy, whole and perfectly normal. Often all it takes is for someone to accept them with love. Love calls them out of the tomb. Knowing that they are loved and lovable enables them to “come out,” in common parlance. And they see that they are not rotten at all, but beloved children of God and valuable members of the community.

In my ministry with LGBTQ people, I sometimes meet people who believe they were created in a faulty way, that there is something deeply wrong with them, that they are “rotten.”

Likewise, some of us may be ashamed of some sort of disability, physical or otherwise. Rick Curry, a Jesuit brother who was born without a right arm, often told a story about growing up in the 1950s as a boy with a disability. In those years, the right arm of Saint Francis Xavier, a relic from the famous Jesuit missionary, was coming to Philadelphia to be venerated. (Catholics often find comfort in the physical connection to the saint that a relic provides.)

Not surprisingly, Rick’s Catholic school classmates were eager for him to visit the relic so he could be “cured.” After all, Rick was missing an arm, and here was St. Francis Xavier’s arm coming to Philadelphia. His class started to pray for a miracle.

Rick made the trip to the cathedral in Center City and pressed himself tightly against the glass case that held that body part of the saint. Perhaps proximity to this famous right arm, and the prayers of this great saint, might miraculously restore Rick’s own right arm.

When Rick returned home, he was the same as ever. His younger sister, Denise, said, “I’m so glad that nothing happened, because I like you the way you are.”

It was a pivotal moment for Rick, which he spoke of often. Love had called him out of the tomb. What seemed rotten to others was perfectly healthy to his sister, and to him. And, of course, to God.