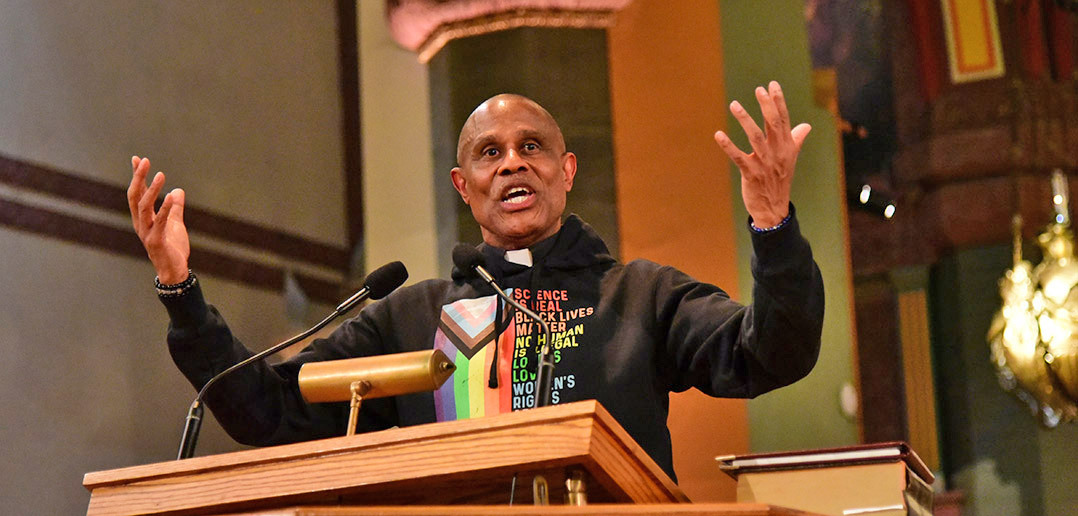

The following essay was adapted from an addressed delivered by the Rev. Bryan N. Massingale during the Ignatian Q Conference, a gathering of LGBTQ students from Jesuit colleges and universities, held at Fordham University on April 21.

I come to you as a Black, gay priest and theologian. I am informed not only by my sexuality, my faith and my study of the church’s ethical beliefs, but also by the traditions of Black freedom struggles in the United States. These struggles, at their core, are matters of the soul and the spirit. And so, I will speak to you out of my whole self, for my sexuality, my faith, my vocation and my racial identity inform all of who I am.

But for my emotional and spiritual health I cannot, and for my moral and ethical integrity I will not, bracket my “Black” self in order to be “gay,” so you can take what makes you comfortable. You have to take all of me or none of me. I don’t want to spend my energies building a church or a world where only part of me is welcomed, valued and loved. Because if you accept only part of me, then you are not accepting me!

As I thought about what I wanted to share with you, the phrase “dreaming while queer” came to me. I want to speak of about the power of dreams. Of dreaming while queer. Of dreaming as Black and queer person of faith.

Dreams are what propelled people to do outrageous and dangerous things for the sake of justice.

Like most of you, I am Jesuit-educated: Marquette University, Class of 1979. When I was an undergrad, I could scarcely dream of a day like this. If anyone had told my 21-year-old undergrad self that someday if I would be addressing a gathering of LGBTQ students from Jesuit universities as a Black, publicly gay priest, I would have laughed and said, “In your dreams!”

When I was a professor at my alma mater, and wanted to teach a course on homosexuality and Christian ethics, I was told it couldn’t be taught in the theology department but only in the honors program. If you had said that ten years later I’d be here, I would have said, “Only in your dreams.” Yet folks like us dreamed. And because they dreamed, we are here.

Langston Hughes—a Black, queer, sexually non-conforming poet of the Harlem Renaissance—spoke of the power of dreams in his classic poem, “Dreams.”

Hold fast to dreams

for if dreams die,

Life is a broken-winged bird

that cannot fly.

Hold fast to dreams

for when dreams go,

life is a barren field,

frozen with snow.

I have long been taken with the power of the human imagination, especially the imagination of despised and disdained and stigmatized peoples. I am inspired by how, despite all that they, that we, have been through and still endure, yet people dream of new worlds. We persist in the hope that reality not only should—but will—be other than it is.

“Because someday he may need it”

Let me make this concrete by offering two vignettes:

1) One of my prized possessions is a huge gold-leafed, black leather-bound dictionary my grandmother gave me for my eighth-grade graduation. It was The New Webster Encyclopedic Dictionary of the English Language. It contains over 973 pages of definitions, with an additional 500 pages of reference material, including how to write a letter to the president of the United States.

Why would a grandmother give such a gift to a 14-year-old boy living in Milwaukee’s inner city? Her response: “Because some day he may need it.” “Because some day . . . ” That is the essence of the Black imagination. My grandmother was not delusional. She did not live in denial of reality, of the fact that our neighborhood store was called derisively “rats and roaches incorporated” by my siblings and I.

Her gift was a vision, an act of hope. It was a dream, a hope, a reminder that the neighborhood, with its drugs, violence and rodent-infested corner store with overpriced goods, did not define or limit who I could be. Her gift was a conjuring of imagination. My grandmother dreamed while Black.

2) Sixty years ago, a young Black minister addressed what then was the largest assembly of civil rights protesters in the nation’s history. He recounted the nation’s legacy of broken promises, which he described as checks returned marked “insufficient funds.”

He narrated the “great trials and tribulations” that so many had endured: harassment, beatings and the horrors of being crammed in dank, narrow jail cells for their convictions. Yet, he implored them to return and continue with their grinding, treacherous and dangerous work for justice:

Go back to Mississippi, go back to Alabama, go back to South Carolina, go back to Georgia, go back to Louisiana, go back to the slums and ghettoes of our northern cities, knowing that somehow this situation can and will be changed.

Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., “I Have a Dream,” August 28, 1963

And then, at the urging of the gospel singer Mahalia Jackson, he shared a dream: an inspirational vision of what one day will be because of what they dared to do now. Martin Luther King dreamed while Black.

In our tech-centered Western culture, with our overly rational educational systems, we tend to disparage songs, poetry and dreams as being impractical and of little importance. We dismiss them as distractions, as illusions and even as derelictions of duty and abdications of responsibility.

But I want to say: No! Dreams are what propelled people to do outrageous and dangerous things for the sake of justice.

We gather this weekend to speak of queer activism rooted in love and justice. The Black historian and social critic Robin D.G. Kelley is correct when he observes, “The catalyst for political engagement has never been misery, poverty and oppression but the promise of constructing a new world.”

Kelley continues, “Dreaming means creating spaces for collectively imagining alternatives . . . and then planning to bring them to fruition.”Or, as he says more poetically, it is envisioning “somewhere in advance of no where.” It is envisioning a world that does not yet exist, but must someday come to be.

Note how imagination and dreaming are born out of dissatisfaction with the status quo. Imagination and dreaming express subversive agency. Both terms are important. Social movement imagination, and particularly queer imagination, has an inherently subversive quality.

Dreaming is a first essential step to creating a new and more just social order.

Queer imagination and dreaming expresses dissatisfaction with, and even alienation from, dehumanizing and oppressive circumstances. By dreaming alternatives to “the familiar,” imaginative communities of the stigmatized expose and exceed the limits imposed upon them.

Indeed, the act of dreaming and imagining is already one that creates the alternative for which they long. Dreaming is a first essential step to creating a new and more just social order. One of the three Black queer women founders of the Black Lives Matter movement, Alicia Garza, conveys the subversive agency of imagination when she writes:

When we create spaces that allow us to be our full selves, unapologetically, we are engaging in acts of resistance and liberation. . . . [We] defiantly [take] up more space than we are given. . . . We are choosing to live in the world that does not yet exist but one day will surely come.

Thus, one of the most essential tasks of any social movement is the “abolition of imaginative slavery” and the willingness to “take our imaginations seriously.”

Revolutions and social change are not singular events, “but long dreams, shared by aggrieved communities, nurtured in fugitive spaces, and enacted by social movements.” So, our work is to let this be a space for our dreaming, for queer dreams.

Because the dream of a place where all are welcomed, where people of every sexuality are valued, where all gender identities are respected and protected—that dream is not yet realized. And not only is it not yet realized, it is under attack in blatant, disturbing and even frightening ways that many of us thought and hoped were behind us.

In an ever-growing number of places, there are laws that seek to erase our existence. Transgender persons are being refused life-saving gender-affirming medical care. Books that speak of LGBTQ lives and history are being banned from school libraries. Teachers who mention the words “gay,” “lesbian,” or “queer” are being fired. At an unprecedented rate, states are passing laws that prohibit the discussion of LGBTQ topics in schools and even workplaces.

In many parts of the world, it is a capital crime even to be suspected of being same-sex oriented or gender nonconforming. This is not an overstatement: There are serious efforts underway to create a world in which we do not exist.

Moreover, while it is good for us to be here, we must also be honest and face that there are some, perhaps even many, who are not here. Not only because of the crush of school work. Not only because of a lack of funding. But there are those of us who are not among us now because they have been so hurt, so wounded, so traumatized, by their church, synagogue, temple or mosque that they cannot be here. Some are not here because they find nothing life-giving about this space.

Let’s be honest and acknowledge that there may be people in this room who have come bearing wounds and scars of exclusion, of hatred, of lack of understanding. All of this is here, in this space. (So we need to be gentle and loving of one another).

You might be saying, “That’s a downer! That’s heavy.” And that’s okay. Because remember: Dreams and dreaming are not a denial of reality. Queer dreams and dreaming are not fantasy or escape. They are not illusions or delusions. Yes, there are many in church and in society who do not understand us, who fear us, who seek to censure and erase us.

And yet, still, we dream. Still, we dream. We dream, like my grandmother, who said, “One day, you will need this,” despite all that is going on around you. We dream with the Black gay actor and activist, Billy Porter, who refused the lie that he was unworthy and lives for the sake of a dream. We dream, as Harvey Milk did, when he said, “You gotta give them hope.”

The dream of a place where all are welcomed, where people of every sexuality are valued, where all gender identities are respected and protected—that dream is not yet realized.

We dream, inspired by Silvia Rivera and Marsha P. Johnson, trans persons of color and gender-bending activists of Stonewall. We dream with the witness of John McNeil, a trail-blazing gay theologian and counselor who was dismissed from the Jesuits for his ministry and yet continued his work informed by the Ignatian spirituality that sustained him.

And we dream inspired by our faith. We dream in the words of Jesus: “Peace is my gift to you.” Peace. He most likely used the Hebrew word, shalom, which means so much more than “peace.” It means wholeness and fulfillment, a world where no one—no one—lacks for what they need for abundant life. A world where no one lacks because of their gender, gender identity, gender expression, or because of who they love, how they love and how they seek love.

Yet still, we dream. We dream. We dream that we will be, in Ignatian language, hominis pro allis—people for others. That we will engage in activism for justice rooted in love. We dream Ignatian-inspired visions.

God’s beloved

I was privileged to make the 30-day retreat. It’s a time of intense prayer over a four-week period. The title of the fourth week of Spiritual Exercises is “the contemplation to attain God’s way of knowing.”

After coming to know yourself as a loved sinner, as God’s Beloved, making a fundamental decision to follow Christ, accompanying Christ through his life and death and coming to a deeper understanding of the crucifying pains of one’s own life, you pray for the grace of knowing and loving the world (the cosmos/reality) with God/Christ’s love.

Ignatian spirituality summons us to see the world as Christ sees it. To love ourselves as God loves us. To love each other as God loves us. To see and love “the other” as Christ does.

Ignatian spirituality summons us to see the world as Christ sees it. To love ourselves as God loves us. To love each other as God loves us. To see and love “the other” as Christ does.

Thus we need to assert, without apologies, the precious value of LGBTQ lives. Of our lives. We need to confidently and insistently proclaim that we are equally redeemed by Christ and radically loved by God.

We are equally redeemed by Christ and radically loved by God. We can never say that often enough. We need to tell ourselves and one another over and over again: “You are loved. You are lovable. You are sacred. Because you are God’s image.”

We must refuse the lies put forth by white supremacy and heterosexism. We need to pray for the grace to see and love ourselves, our world and each other as Christ knows and loves us. The grace to dream God’s dream for us.

So let us dream. To be hominis pro aliis. To be people for others. Working for justice. Working in love. Working in faith. To co-create with God a new future. To dream and then to “go forth and set the world on fire.” To be people for and with others.

What keeps me dreaming while Black and queer, even when I’m tempted to accept a pessimistic interpretation of reality, is the memory of my grandmother. Once, during conversation with my spiritual director, I poured out my anger and frustration at the futility of working for racial and sexual justice in a Catholic Church that seems impervious to any appeal or change. “Why in the hell should I keep doing what I do when it makes no difference in this church?”

She listened patiently and compassionately. At the end of my tirade, she asked, “Where would you be if your grandparents thought as you do?”

That’s why I hold onto that book, even though I seldom use it anymore for its intended purpose. Everything it contains I now can find more easily on Google or by asking Siri or Alexa. I hold onto it, and cherish it, because it is an ever-present reminder of those who dared to dream, and who through their dreams brought and bring something new into the world. It encourages me to continue to dream.

We are equally redeemed by Christ and radically loved by God. We can never say that often enough.

I still have dreams

And so, I still have dreams. I dream of a time when the LGBTQ community will see racism as their issue because it already is our issue. I dream of a day when two men and two women can stand before our church, proclaim their love and have it blessed in the sacrament of marriage. I dream of a church that enthusiastically celebrates same-sex loves as incarnations of God’s love among us.

I dream of a church where gay priests and lesbian sisters are acknowledged as the holy and faithful leaders they already are. I dream of a world where queer young people in Honduras, El Salvador, Uganda, Kenya and Afghanistan can step out of hiding and live without fear. I dream of a church where LGBTQ employees and school teachers can teach our children, serve God’s people, and have their vocations, sexuality and committed loves affirmed.

I dream of a LGBTQ community committed not only to respect for sexual diversity, but also for immigration justice and equal voting rights. I dream of a LGBTQ community that is as passionate about justice for Black and Brown trans people as it is about justice for white cisgender men. I dream of a LGBTQ community that embraces its diverse palette of skin tones as a marvelous reflection of God’s own interior life of diversity.

I dream of a church that enthusiastically celebrates same-sex loves as incarnations of God’s love among us.

I dream of a church that reflects the joy of the wedding banquet at Cana, where people of all races, genders and sexualities rejoice at the presence of love and commit themselves to make a world where people of every gender and race live the fullness of life that God desires for all.

So hold fast to dreams this weekend. Let your heart and your spirit soar. Let your spirit be borne on the wings of the Spirit. And dream of that world where spiritual wounds will be healed, where faith-based violence will be no more, where fear and intolerance are relics of history. We are called to dream. To keep dreams alive. To hold fast to dreams!

Hold fast to dreams

for if dreams die,

Life is a broken-winged bird

that cannot fly.

Hold fast to dreams

for when dreams go,

life is a barren field,

frozen with snow.