This is the first part of an article on Catholic Latinx LGBTQ ministry. The second part, which discusses action steps, will be published tomorrow.

Part I

Hispanic Heritage Month, which is commemorated annually from September 15 to October 15, has brought about significant celebrations of our Latinidad and the many beautiful traditions associated with it. However, in the past, I often struggled fully associating myself with these celebrations as a Puerto Rican Catholic theologian, who also identifies as gay.

While I proudly claim my Puerto Rican identity, I must also admit that the culture of the island on which I grew up remains largely oppressive and exclusive to many members of my LGBTQ community. Therefore, I have had to embark on a complex journey toward integration of my gay, Latinx and Catholic identities in order to serve as a guide to other Latinx LGBTQ Catholics who face a similar struggle.

A large part of this journey involved a process of deconstruction and reconstruction of my Latinidad, LGBTQ identity and catholicity in a way that leads to personal integration and social transformation. Drawing from this experience, I hope to reflect on what it would mean to effectively minister to Catholic, Latinx LGBTQ people. I am organizing these reflections following the traditional cycle of awareness, analysis and action.

Awareness

LGBTQ exclusion is not unique to Puerto Rico: I perceived the same trend in other Latinx communities through my work as a high school educator and mentor of LGBTQ youth for over ten years. As I worked with my LGBTQ students, I noticed that many of my white students seemed to have more self-confidence about their queerness and better relationships with their parents, who were accepting of their sexual identity.

Conversely, many Latinx parents struggled to accept their LGBTQ children, often citing religion as a primary motive for their rejection. There were exceptions on both sides, but this was an overall trend I noticed.

Obviously, there needs to be more research on this matter—and I would never claim to speak on behalf of all Latinx people. But my experience as an educator, theologian and Latinx gay man leads me to suspect that perhaps the struggles toward acceptance of LGBTQ people in Latinx communities is closely related to the way Latinx culture has historically conceived of gender relations.

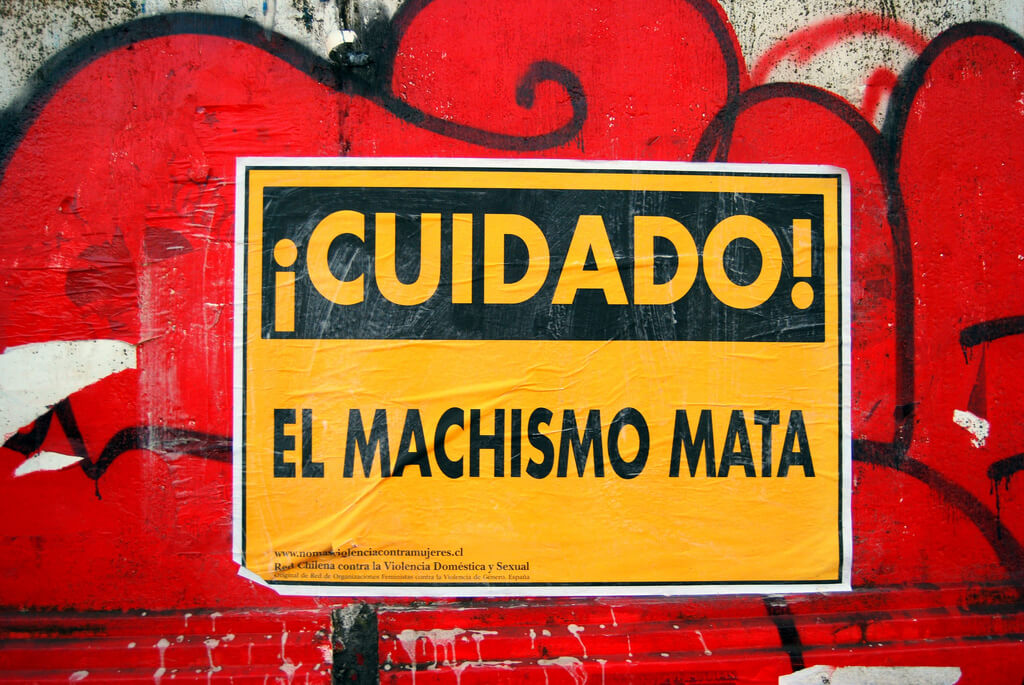

Many of us are familiar with the Spanish word machismo, which is the commonly used word for “sexism.” I tend to stay away from that word because it seems to suggest that machismo sexism is a uniquely Latinx issue—and it is not. However, I also concede that there are some distinct ways in which sexism manifests in Latinx American countries.

As I will demonstrate, I do not believe that Latinx culture itself created machismo. Rather, I argue that machismo stems from a combination of many factors permeating Latinx culture (though not essential to Latinx culture), including colonialism, Christian theology and traditionalism.

“It is clear that this heteronormative machista culture leads to exorbitant levels violence toward LGBTQ people, who are murdered at alarming rates in Latinx America.”

Crucially, a central component of machismo is heteronormativity, which is the expectation that everyone is heterosexual and would live a heterosexual lifestyle by marrying someone of the opposite sex and having children with that person. Thus, machismo attitudes in Latinx America seek to preserve the current gender relations under male dominance through the active promotion of a patriarchal, hegemonic, heterosexual lifestyle.

The effects of machismo are devastating for LGBTQ youth, who are often called “sissy,” “maricón,” or “bucha”(the latter two are Spanish words for “f–ggot” and “butch”), and other insults when they fail to live up to a male-dominant heteronormative standard. Even worse, it is clear that this heteronormative machista culture leads to exorbitant levels violence toward LGBTQ people, who are murdered at alarming rates in Latinx America. (Four LGBTQ persons are killed in that region per day, according to this 2019 study.)

These crimes often receive inadequate response from law enforcement. For example, after a transgender woman named Alexa was shot and murdered in Puerto Rico, a police report described the assailants as having shot down “a man in a skirt.” Furthermore, this machismo violence extends beyond the LGBTQ community and affects heterosexual cisgender women as well. Boston College professor Nancy Pineda published a book on femicide in the city of Juarez and, in 2021, Puerto Rico declared a state of emergency over violence against women.

Anaylsis

Ministering to Latinx LGBTQ people (and ultimately helping us dismantle the machista attitudes that are ingrained in our psyche) first requires an understanding of machismo culture and its three founding components of colonialism, Christian theology and traditionalism.

First, colonialism is clearly ingrained throughout Latinx culture through historical military and economic imperialism at the hands of different European powers and the United States. The effect of this historical colonialism still impacts Latinx American countries today. Most importantly, those violent power dynamics between different ethnic and racial groups crossed over from economic imperialism into power dynamics between genders.

In other words, the quest to control and dominate, which has roots in racial and ethnic oppression, is also prominently deployed by men in an attempt exercise power and dominion over women. This is the meaning of “the patriarchy.”

Second, Christianity has historically provided significant theological justification for this power differential. Doctrines elevating the maleness of the priesthood due to Jesus’ own sex and the sex of the 12 disciples, biblical passages containing double standards against women and referring to men as the head of the woman (as Christ is the head of the church) and other theologies grounded in natural law that defend male dominance have permeated Christian narratives in Latinx America.

Essentially, Latinx culture operates under a de facto Theology of the Body. Furthermore, religious imagery throughout Christian history has predominantly depicted Jesus and God as a white, heterosexual, cisgender male, further perpetuating power dynamics over matters of race/ethnicity and sexual/gender identity.

Third, traditionalist attitudes also permeate Latinx America. I recall through my upbringing that there are certain cultural norms that one is expected to follow without question. This is also evidenced in a religious devotionalism in which people would engage in a particular activity without necessarily knowing its origin or even its meaning.

Sometimes people preserve these cultural norms and transmit them to their children through socialization and education without necessarily knowing why. This is particularly prominent in fundamentalist Christian denominations, which are on the rise in Latinx America.

A culture of male power and domination, theologies claiming gender roles are divinely ordered, and a mindset that discourages the questioning of social norms creates a type of sexism, or machismo, that is prominent and prevalent in Latinx culture.

“Christian (and particularly Catholic) theology on gender, combined with male-dominated religious imagery, are often used to justify machismo attitudes that oppress women and LGBTQ persons.”

As stated, a central feature of this machismo is heteronormativity, which includes an expectation of male dominance as part of the heterosexual lifestyle. In other words, the husband needs to be the man of the house, the provider and the controlling interest, while the woman is the submissive caretaker who defers to her husband on important family decisions. In fact, the word maricón is often levied at young men if they are unable to conquistar (conquer) and exercise control over another woman.

This expectation of heteronormativity is transmitted through education and socialization, and it is particularly oppressive to LGBTQ youth. For example, if a gay male child discloses this homosexual identity, that so-called maricón is often thought of as “not man enough” because of his lack of desire for women. Likewise, if a female child discloses a lesbian identity, she is adversely characterized as a bucha because she is not “pleasing a man” or “submitting to male authority.” In fact, accusations of a lack of submission are often also levied against heterosexual women who are vocal feminists in Puerto Rico.

For trans people, this heteronormative and cisgender-normativity is even more oppressive. Trans people are directly disrupting the male-female gender binary and are, therefore, perceived as more threatening. Society often responds by erasing trans identities in an attempt to perpetuate the gender binary and, with it, the power relations that exist between men and women.

This involves a refusal to adopt the slowly emerging gender neutral pronouns “elle” and “elles,” as well as gender neutral conjugations (e.g. “niños, niñas, niñes”) and the characterization of trans people as pathological cross-dressers.

As stated, Christian (and particularly Catholic) theology on gender, combined with male-dominated religious imagery, are often used to justify machismo attitudes that oppress women and LGBTQ persons. These theologically-backed machista attitudes also permeate Latinx communities in the U.S. through immigration. As a result, LGBTQ Latinx people—whether born in the United States or in a Latinx country or territory—often carry the traumas of such exclusion and associate the traumas with Latinx culture and its predominant Christian worldview.

In my experience ministering to Latinx LGBTQ Catholics, I have noticed that many of them struggle integrating their LGBTQ identity and their Catholic Latinidad. This oppression causes serious spiritual harm. I do not believe that the God of the Israelites, who shaped their particular cultural context in which Jesus became incarnate, would justify the creation of cultures that cause disintegration and oppression.

On the contrary, Jesus’ interaction with (and transformation of) his own culture is indicative of God’s will, in which cultures serve as an avenue toward flourishing. For this reason, those of us who offer care to Latinx LGBTQ Catholics have a task to guide the people under our care in a journey toward integration, social transformation and ultimate flourishing.