The following is an essay adapted from Mychal Judge: Take Me Where You Want Me to Go, written by Francis DeBernardo and published by Liturgical Press. Outreach has maintained the style and conventions of the published text.

Postscript: When the World Seems Its Darkest

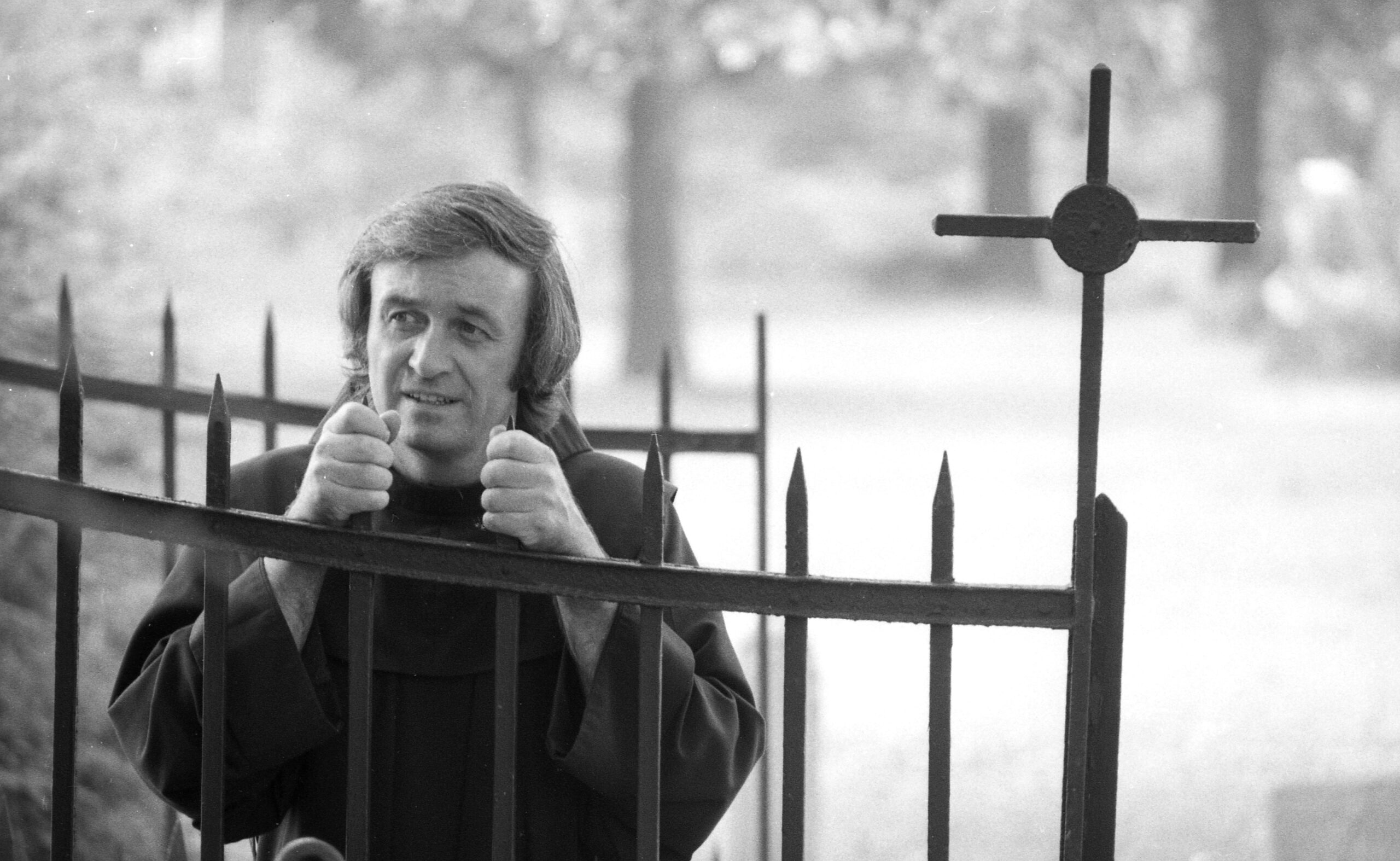

Father Mychal Judge ran into the fiery inferno of a crumbling building as others were running out of it. Why did he put himself into a dangerous situation when the option to stay in a safety zone was available to him? While we can’t learn the motivation from him directly, the story of his life provides enough evidence to construct a plausible answer.

By running into the North Tower of the World Trade Center so that he could minister to those suffering, Judge was responding in a way that had become second nature to him. His sixty-eight years of life, prayer, community, and ministry had made him into a person who valued relationship over self, service over prestige, the suffering Christ over power and riches.

Judge’s decision to act on 9/11 was not because he was a superhero. He would be the first to admit so. He had no special powers that were unique to him. He would say just the opposite. Whatever power he had was a power that is available to all. Judge’s spiritual strength came from his utter dependence upon God to care for him and guide him.

No doubt his childhood Irish Catholicism began teaching him this habit, but certainly his Franciscan formation developed it, and his AA spirituality confirmed it in him. In his 1999 journal, he prayed, “Oh Lord—you know me so well—I can’t hide from you—I have nothing, nothing to fear—All I have to do is your will and all will be well—Make it known to me.”

The prayer that he composed for himself and frequently shared with others reflects this attitude (as well as his gift for self-deprecation): “Lord, take me where you want me to go. Let me meet who you want me to meet. Tell me what you want me to say, and keep me out of your way.”

“As a true Franciscan, he didn’t need to look to the heavens for God. He found God in the world.”

Throughout his lifetime, Judge had developed a particularly personal and intimate relationship with God. His ministry flowed from this relationship. His experience of God’s goodness and grace inspired him to want to share these gifts with other people, to help them experience that too. His habit of spontaneously blessing people and breaking into conversational prayer during his ordinary encounters with others was a sign of this intimacy that he experienced with God.

As a true Franciscan, he didn’t need to look to the heavens for God. He found God in the world. He had developed the ability to see God’s presence in the most unlikely of places. God for him was a part of everything, and everything in the world could teach people something about God. He didn’t exhort people to be good; he encouraged them to see the goodness that God had already placed in their lives.

If people could not see that, he was always ready to point out their goodness for them. He reached out to people regardless of whether or not they responded to his gentle invitation to recognize God in their lives.

Judge was no Pollyanna, though. His own experiences of brokenness were enough reminders to prevent him from pretending that pain and suffering did not exist. Yet his life had also taught him that pain and suffering were not the end of the story. His heart could be so available to other people’s pain because he was keenly aware of what pain felt like.

He could reach out to the alienated because he knew the experience of marginalization. He had a gift for accepting people as they were because he had come to accept himself. He could build community so naturally because community and companionship were experiences that he sought for himself too.

As a gay man, a gay priest, growing up in a time of intense discrimination, Judge faced a difficult challenge to accept himself. Both society and the church were telling him that he was “less than” and unworthy of love.

But Judge’s intimate relationship with God helped him to accept himself, which in turn helped others to accept themselves, too. His self-acceptance, as well as his intense awareness that God loved him just as he was, allowed him to minister effectively to the LGBTQ community and to those suffering from HIV/AIDS.

Judge’s life touched on so many of the most important social and cultural issues of the closing half of the twentieth century and the brink of the twenty-first.

He grew up in the immigrant church, embraced commitment in a world of instantaneous change, ministered in the wake of the great changes of Vatican II, confronted addiction in an “anything goes” culture, resolved questions of sexuality in an era of permissiveness, attended to the needs of the poor and marginalized during a time of immense prosperity, cared for people with the most dreaded, deadly, and debilitating disease of his era, and faced the horror of international terrorism.

“As a gay man, a gay priest, growing up in a time of intense discrimination, Judge faced a difficult challenge to accept himself.”

Most importantly, Judge’s life story asks and answers one of the most important questions of the twenty-first-century environment: In a world where unspeakable tragedies occur with breathtaking frequency and where so many traditional patterns of civilized human relationships keep breaking down, where does one find God?

Put another way, where was God on 9/11? Judge would encourage us to see that God was not absent on that day. God was present in the heroic acts of self-sacrifice that the first responders offered. God was present in the many quiet acts of care and concern people offered to injured and frightened people, and to those who were mourning inconsolably.

And God was present in the prayerful witness of Fr. Mychal Judge, who could have stayed on the sidelines but who knew that his place was to be with the people he loved and served. Judge’s life reminds us that we are responsible for manifesting God’s presence in the world, especially when the world seems its darkest.