Editor’s note: This article is the first part of a three-part series by the Rev. William Hart McNichols, a priest of the Archdiocese of Santa Fe, N.M. Father McNichols, a well-known artist and iconographer, was among the first priests in the U.S. to minister to H.I.V./AIDS patients in the early 1980s. Today, he continues his work among the LGBTQ community. The second part can be found here.

Part I

“In the middle of the journey of our life / I came to myself within a dark wood / where the straight way was lost. / Ah me! how hard a thing it is to tell / what a wild, rough and stubborn wood this was / … So bitter it is, death itself is little more; / but of the good to treat, which there I found, / speak will I of the other things I found there.”

—from Canto I, Dante Aligheri’s “Inferno”

When Dante wrote the words above, he was just 35 years old, but his lengthy masterpiece was not completed until 1320, a year before he died. Two years ago marked the 700th anniversary of the completion of his Divine Comedy.

In his epic poem, Dante is not kind to gay people. Until 2002, there was a gay bar (and former steakhouse) in Manhattan’s West Village called the Ninth Circle, referencing Dante’s cruel placement of gay people in his work. In 2020, the author and psychotherapist Mark Vernon wrote: “The poem is many things: a diatribe against the church, a celebration of human qualities, a warning that this life matters, a path of awakening, an odyssey. It was born of a mid-life crisis.”

From the opening lines of the “Inferno” came the 1987 Tony Award-winning, Stephen Sondheim-penned musical, “Into the Woods,” which was, in part, an allegory for the H.I.V./AIDS crisis. This funny, sad and brilliant musical features these haunting words: “Sometimes people leave you / Halfway through the wood / Others may deceive you / You decide what’s good / You decide alone.”

As a Roman Catholic priest, I can honestly say that I don’t decide alone, but as for consigning all us gay people to hell, I agree with another spiritual mentor, the Swiss theologian Hans Urs von Balthasar. In his book, Dare We Hope? he writes that Christians are always damning each other to hell. Dare we hope that all will go to heaven? Isn’t that God’s hope, too?

I was 31 years old when I arrived in New York in 1980. I had been ordained for only a year, and a kind Jesuit mentor warned me I had better get a degree in art if I wanted to be taken seriously. So I applied to the Pratt Institute of Art in Brooklyn and started classes in the fall of that year, after spending that summer helping out at St. Mark’s Church in Sheepshead Bay.

For the first time in my life, I was given permission, by a kind and loving Jesuit superior, Jim Blumeyer, to live alone. I found an apartment for $350 a month at the top of a brownstone at 361 11th Street, in the Park Slope neighborhood of Brooklyn.

There, I could go out the fire escape and climb to the roof to see a glorious view of Manhattan. People warned me I’d be lonely and lost, but living alone, I could listen to and hear God in a way I cannot describe. My imagination led me into great bursts of creativity which lasted the whole three years I lived in Brooklyn.

This was also a time of enormous creativity and scholarship in the gay community, a time that produced several life changing books that I devoured: Christianity, Social Tolerance, and Homosexuality, by John Boswell; The New Testament and Homosexuality, by Robin Scroggs; and the landmark text The Church and the Homosexual, by the then-Jesuit John J. McNeill.

“People warned me I’d be lonely and lost, but living alone, I could listen to and hear God in a way I cannot describe. My imagination led me into great bursts of creativity which lasted the whole three years I lived in Brooklyn.”

From this journey into gay history, a flood of colored pencil drawings came rushing out of me. I was pouring my soul out and my own healing journey began. Presently, I am working on a volume for Orbis Books with the brilliant theologian Christopher Pramuk; the book will contain drawings, paintings, images and icons.

My goal in life, at that time, was to be a children’s book illustrator. This was before the internet, emails or iPhones, so I’d walk all over Manhattan with my portfolio, trying to get a job. Every publisher would ask the same question: “What books have you illustrated ?” I’d say, “Well, none yet but if you give me a chance…” and then doors shut.

Finally, I entered a contest for Paulist Press with a 1982 book teaching children the history of Catholicism through its architectural masterpieces. And lo and behold, I won. After that, I illustrated about 20 books for Paulist Press, the Episcopal publisher Seabury Press and other works for children and adults.

At the same time, I was invited to be a celebrant for the LGBTQ Catholic community Dignity, which held Masses every Saturday evening at the Church of St. Francis Xavier, in the Flatiron District, until the group was expelled from the parish in 1987 by Cardinal John O’Connor of New York. In those days, if you were a celebrant for a Dignity-sponsored liturgy, it was assumed you were gay. No other priests were interested, but they weren’t hostile either.

It was an exhilarating time for gay people. The uprising at the Stonewall Inn in 1969 had freed LGBTQ New Yorkers, and at Dignity, I met gay clergy, policemen, firemen, lawyers, doctors and all kinds of professional men and women. Almost every straight New Yorker was proud to have a gay friend, and it seemed like we were finally accepted.

At this time, I was immersed in my study of scripture through my favorite biblical scholar, the English-born George Bradford Caird, who had written two commentaries—one on Saint Luke and another on the Book of Revelation—which I had loved. I’d read them on the subway, and once again, the colored pencil drawings kept coming from my studies.

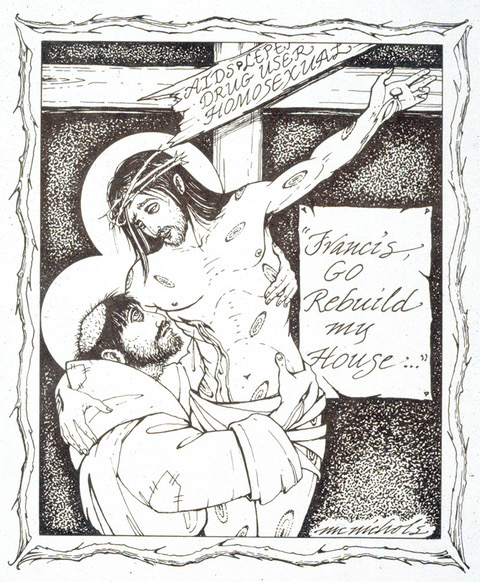

In 1982, I was commissioned to create a slideshow and music presentation for the Church of St. Joseph, in Greenwich Village, in honor of the 800th anniversary of the birth of Saint Francis of Assisi. Some Third Order Franciscans came down from the Bronx to see it.

Then, they invited me to their house, called “The Little Portion” after the Porziuncola in Assisi, to share my slides and soundtrack. This led to me being accepted into the Third Order in 1984, and meeting another whole host of new friends, including the Franciscan friar André Cirino.

André loved my art and encouraged me to see it as my vocation. I did many drawings of Saints Francis and Clare for them. I had always been focused on something Saint Ignatius had written in his autobiography: “What if I should do what St. Francis did?” and “What if I should act like St. Dominic?”

I took those words to heart and tried to find the essence of both saints in my Jesuit vocation. St. Francis began his vocation by embracing a leper and wanted his novices to work with them because, he said, the leper is Christ. The Dominican motto contemplata aliis tradere, which means “to hand down the fruits of contemplation,” gave me another set of wings to share my art.

One day, from my roof in Brooklyn, I photographed seriously foreboding thunderclouds moving across the city towards us. I was in the midst of my study of Caird’s The Revelation of Saint John the Divine, and I had just purchased Damien the Leper, by John Farrow.

When I finished the book, I said in my prayer, “Send me.”

Next in this series, Father McNichols recalls: “My first visit to a man dying of AIDS left me staggering onto the streets of New York. He was lying in a bed, visibly emaciated, with his mother on one side of him and his lover on the other. Both were weeping.”