Mark McDermott, a retired partner at the New York law firm Skadden, Arps, Slate, Meagher & Flom, is a donor and contributor of Gospel reflections to Outreach. His husband, Yuval David, is an actor, filmmaker and LGBTQ rights activist. He is the director of the forthcoming documentary, “Wonderfully Made – LGBTQ+R(eligion),” premiering Saturday, September 24 at the Out on Film Festival in Atlanta.

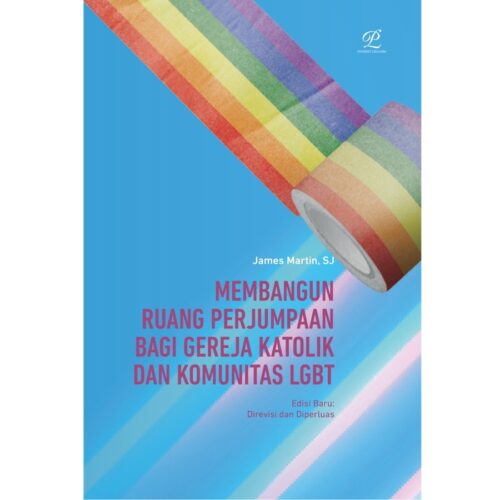

In April 2019, we called our good friend, James J. Martin, S.J., with a mustard seed of an idea: Would he, and others who minister to LGBTQ Catholics, find any value in some new iconography that depicts Jesus as suffering with and for LGBTQ people?

The idea arose from Mark’s search for Christian iconography that represents the LGBTQ community. He found a few things, but nothing that spoke to him. “If you cannot find it,” said Yuval, “why don’t we create it ourselves?” Mark readily agreed.

Our idea was very vague at the time. We knew we would create it ourselves with the help of a photographer and a few actors, but we had no idea then that it would blossom into a three-day photo shoot with one of the best photographers in the world, over 13,000 pictures of nine actors of diverse ethnicities, sexualities and gender identities and a feature-length documentary.

The film required over 150 people to produce, featuring 390 pieces of archival footage and 43 separate music sequences, most of it originally scored and performed. This included an a cappella performance by an Israeli choir of the “Hymn of the Cherubim,” a soaring composition from Tchaikovsky.

We have been at the helm of this project these last three and a half years, journeying together as husbands, soulmates, best friends and co-producers, as we navigated the often heavy seas of creating an indie documentary.

We have all heard that God is in all things, including all people. The word “all” means “all”—it admits of no exceptions. We have heard that we are all created in the likeness and image of God, too.

As Pope Francis has said about our LGBTQ brothers and sisters, we are all God’s children. What better way to show this, as storytellers, than with imagery that depicts Jesus not solely as white man of northern European descent, with blond hair and blue eyes, but also as Black, Asian, Latino, Middle Eastern, male, female and LGBTQ?

The idea arose from Mark’s search for Christian iconography that represents the LGBTQ community. He found a few things, but nothing that spoke to him. “If you cannot find it,” said Yuval, “why don’t we create it ourselves?”

“One of the most important things we can do is to proliferate our images, and that way it opens your imagination and allows you to see God in a new light … [and] maybe to see the neighbor next to you in a new light,” said Natalia Imperatori-Lee, a professor of religious studies at Manhattan College.

Sister Jeannine Gramick, S.L., whom we also interviewed in the film, repeated Pope Francis’ words. “We are all children of God,” she said, “and we need to understand that message so that no one will be on the outside, so there won’t be any fences, that we will all be welcome.”

We hired a top casting director, Amy Gossels, to help us. We weren’t sure how to proceed or whether any actors would be interested. How do you cast people for a role like this?

We were shocked by the reception: Over 500 actors auditioned. That’s when the mustard seed sprouted. It shot upwards and outwards when Yuval’s friend, Brendan Cannon, got involved. He’s a major fashion stylist and creative producer, having produced photo shoots for Michael Jackson, Liza Minnelli, Angelina Jolie and Glenn Close. (He’s also a gay alumnus of Xavier High School in New York City.)

He understood our vision immediately, and brought in Lindsay Adler, a sought-after photographer.

We worked closely with them, reviewing hundreds of paintings, drawings and statues of Jesus. We mapped out the poses we wanted, the wardrobe we needed and the make-up and lighting that worked best. Brendan brought in wardrobe designers (one of whom worked on the Harry Potter films), hair stylists and make-up effects specialists. They all came together, after about six months of planning, and performed like the New York Philharmonic.

The first day of the shoot was “simple”: We experimented with only one model. The day lasted 14 hours with 19 people on set. But that experiment was invaluable, allowing us to streamline our thinking so we could photograph the other eight models in only two days (for 14 hours each).

Somewhere along the way, long before we could curate the thousands of breathtaking images that our team created, Yuval had the idea—another mustard seed—to make a brief documentary about the creation of this project. “People love to see behind-the-scenes,” he said. “It’ll be about 10 minutes long.” Mark shrugged and said, “Sure.”

Yuval hired a cinematographer, and their first focus was World Pride in New York, in the summer of 2020. After a long, hot day on the streets, Yuval returned home. “We shot nine hours of footage!” Mark stared and blinked. “What are we going to do with nine of hours of footage?” That was Mark’s introduction to filmmaking, an art Yuval knows well but that Mark had never encountered.

It requires lots of footage, lots of takes, an editing process that is fun and refines the story being told (but that can also feel like slow torture) and a long post-production process that takes more time and expense than any other element of the film.

We now had a big mustard plant—two of them, really—in our condo. “Let’s do some short interviews of some advocates,” Yuval said. “Like Father Jim and Sister Jeannine.”

“Uh, how long will this documentary be?” asked Mark. “Maybe 15 minutes,” said Yuval.

“When you look at the Gospels,” said Father Martin in an interview with Yuval, “you see that Jesus reached out specifically to people who are on the margins. And so, I think if Jesus were here today, in the flesh, he would be going first to LGBT people.”

People on the margins are, in fact, the ones to whom Jesus ministered, and that often seems forgotten today. “Whatever you do for the least of my brothers and sisters, you did it for me” (Mt. 25:40). Indeed, “human beings are of such dignity that God chose to be one,” wrote the late Rev. Michael Himes, a theology professor at Boston College, in 1995. Jesus “did not count equality with God a thing to be grasped, but emptied himself, being born in the likeness of humans” (Phi. 2:5-8).

We did this in the name of hope. We have hope and we want all LGBTQ people to have it, too. We want them to have some images in which they can see their own reflections.

“Whatever humanizes divinizes,” wrote Father Himes. “Whatever makes you more human makes you like God.” These and Jesus’ own words were our pole stars as the two mustard bushes began to crowd us out of our condo. And these words were echoed in our interview with the Rev. Bryan Massingale, a Catholic ethicist at Fordham University.

He crushed us when he said that, while studying in the seminary and undertaking a spiritual exercise focused on Genesis, he saw no Black or gay people in creation. But after four days of grief and agonizing soul-searching, he was struck by the words of Isaiah: “For you are precious in my sight, and I love you” (Is 43:4).

“Amen,” we said.

We heard kernels of wisdom from many of our interview subjects. “I don’t believe God is calling us to throw our kids and young adults out of our houses,” said Stanley “J.R.” Zerkowski, executive director of Fortunate Families, an affirming ministry for LGBTQ Catholics. “You are holy. You have the breath of God within you,” said DignityUSA executive director Marianne Duddy-Burke.

And from Miguel H. Díaz, former U.S. ambassador to the Holy See: “The marginalization and rejection we have experienced must not keep us from offering our rainbow of gifts in service to the church and society.”

We left our condo in New York and moved into a house just outside of Washington, D.C., bringing our huge mustard trees with us. The curating and editing and scoring and sometimes aggravation continued as those trees got so big, we had to plant them in the backyard. We watered them entirely with our own treasure, happy to create this gift for LGBTQ people everywhere. We hoped that it might help bring about some change.

Our favorite part of each interview was the very end, when we showed our interviewees the images for the first time and caught their reactions on film.

The completed film features the voices of almost 30 people, including all the young actors who bravely took on their roles and revealed their authentic selves before the camera. That authenticity is finally revealed at the conclusion of the film, a seven-minute montage of our best images floating across the screen to the echoing voices of the choir.

“What title do we give to this thing?” asked one of our many bleary-eyed assistants after a long day (and night) on set. “Wonderfully Made,” answered our Cuban-born and Jesuit-educated editor, Hugo Perez. “It’s what Father Martin reads from the Bible in his interview.”

Our entertainment lawyer also came up with a great addition to the title. “Add the capital letter ‘R’ after ‘LGBTQ+.’ It stands for religion,” he said.

We’re exhausted. The beauty of creation indeed is a little like giving birth: it saps you of energy and can hurt like hell along the way. But the labor is most definitely worth the tiny being who comes forth, or in our case, the enormous mustard trees in our yard. We’ll share them with the world after the film has run its course on the festival circuit.

We did this in the name of hope. We have hope and we want all LGBTQ people to have it, too. We want them to have some images in which they can see their own reflections. We want to represent the homeless lesbian teen on the streets, thrown out by her own parents; the frightened gay boy in school, bullied because of his voice and his gestures; the non-binary person or the transgender parent, scorned because of how they look; the weeping youth, contemplating his own suicide.

“Have hope, all of you, for you are indeed fearfully and wonderfully made” (Ps. 139:14).