The following is the text of an address delivered by Jason Steidl-Jack during the Outreach conference in New York on June 25, 2022. This essay is adapted from his book LGBTQ Catholic Ministry: Past and Present, published by Paulist Press. This text has been edited for style and clarity.

As a young, married, gay Catholic theologian, I must “always be prepared to give an answer to everyone who asks (me) to give the reason for the hope that (I) have” (1 Peter 3:15). It isn’t always easy to defend my vocation.

Some LGBTQ folks claim that working within Catholic tradition and community harms queer people. They say that Catholic theology is hopelessly queer-phobic and wonder why I don’t just leave it behind. Some cisgender-heterosexual Catholics, on the other hand, argue that my queerness disqualifies me from being truly Catholic.

Embracing LGBTQ identity and being in a same sex-marriage, they claim, is impossible for followers of Christ. How can I negotiate my gay identity and. my calling to be a Catholic theologian? A theology of queer liberation gives me hope that reflecting on God’s work in the world from the perspective of LGBTQ people has the power to transform the Roman Catholic Church.

An LGBTQ perspective on liberation theology

Gustavo Gutiérrez, the father of Latin American liberation theology, describes that tradition as a “critical reflection on praxis in light of (God’s) word.” Liberation theologies originate in contexts of oppression, inequality and dehumanization such as poverty, racism, misogyny, ableism and homophobia.

Rather than thinking about God from the perspectives of the rich, the powerful and the victors of history, liberation theology considers God from the perspectives of those who have lived, suffered and died on the underside of history. It takes the stories of the poor, excluded, and queer seriously as the site of the site of God’s inbreaking kingdom in the world.

Reflecting on the history of salvation as revealed in Scripture and the life of Jesus Christ, liberation theology discovers a God who exercises a preferential option for the poor, that is, one who intervenes and acts on behalf of the suffering.

Liberation theology originated in Latin America the mid-20th century, a time when many believers struggled with an institutional church, whose fortunes were often tied to colonialist and authoritarian governments. For generations, many bishops and priests had sided with the rich and powerful at the expense of the poor and powerless. Religious leaders who were supposed to be agents of liberation served the forces of death. Who could break the church’s collusion with systems of oppression?

Latin American theologians found the answer among the poor. In the 1960s, a movement of “base communities” arose to serve and organize the poor in rural area where clergy were sparse. These grassroots group fostered solidarity through social, political and spiritual action.

A theology of queer liberation gives me hope that reflecting on God’s work in the world from the perspective of LGBTQ people has the power to transform the Roman Catholic Church.

The mutual aid networks that developed throughout Latin America addressed people’s material needs while also resisting the dehumanizing social structures that oppressed them. Base communities opened a new way of being church.

Jon Sobrino, a Spanish Jesuit who was ministering in El Salvador at that time, reflected on the revolution happening around him. Paying attention to life at the grassroots, he saw that God was working among the poor to bring salvation into the world. Unless the institutional church learned from the poor and other victims of human history, it could never be a source of hope within a “gravely ill civilization.”

To build his case, Sobrino cited the work of José Comblin, a Belgian-born priest and theologian who settled in Brazil in 1958. Comblin had observed a wide gap between how the poor were conceived by outsiders and how they lived. He wrote:

The mass media speak of the poor always in negative terms, as those who don’t have property, those who don’t have culture, those who have nothing to eat. Seen from outside, the world of the poor is pure negativity. Seen from within, however, the world of the poor has vitality; they struggle to survive, they invent an informal economy and they build a different civilization, one of solidarity among people who recognize each other as equals—a civilization with its own forms of expression, including art and poetry.

Comblin’s insight into the lives of the poor helped Sobrino reimagine the role of the poor—and the church—in salvation history. Traditionally, Catholics had imagined the church as the normative vehicle for God’s grace, a conviction expressed over the course of many centuries in the maxim Extra Ecclesiam nulla salus (Outside the church there is no salvation).

Sobrino, however, inverted the traditional formulation by asserting Extra pauperem nulla salus (Outside the poor there is no salvation). The experience of the poor, he wrote, “is salvific, for it generates hope for a more human world. And it is an experience of grace, for it arises where we least expect it.”

So, what does all of this have to do with LGBTQ people in the Catholic Church?

Queerphobia and religious communities

Queer folks, akin to the poor in Latin America, have long suffered from social and ecclesial injustices. According to the Human Rights Campaign (H.R.C.), LGBT youth are twice as likely to be physically assaulted than their straight peers. In a 2015 study, LGB youth were nearly five times more likely to attempt suicide in the prior year than their heterosexual peers.

Neither are adults exempt from violence. The F.B.I. reported that nearly 17 percent of hate crimes in 2019 were based on sexual orientation and 2.7 percent of hate crimes were based on gender identity. That same year, at least 44 trans or gender non-conforming people were murdered in the United States.

Tragically, religion often augments the suffering of LGBTQ people. It’s no surprise that queer youth raised by parents with “anti-homosexual religious beliefs” are more than twice as likely to attempt suicide compared to peers with accepting parents.

Carl Siciliano, the founder and executive director of the Ali Forney Center, a New York City shelter for homeless LGBTQ youth, told James Martin, S.J., that at least 90 percent of homeless LGBTQ youth in New York City were kicked out of their homes by their parents for “religious reasons.”

LGBTQ adults are also harmed in the church. Alana Chen was a young woman from Colorado who committed suicide after a priest reportedly encouraged her to hide her lesbian identity. In many parishes, dioceses, and schools, church workers who marry their same-sex partners lose their livelihoods. Some U.S. Catholic dioceses have suggested that the church should deny funeral rites to married sam-sex couples, a final humiliation after so much spiritual abuse in life.

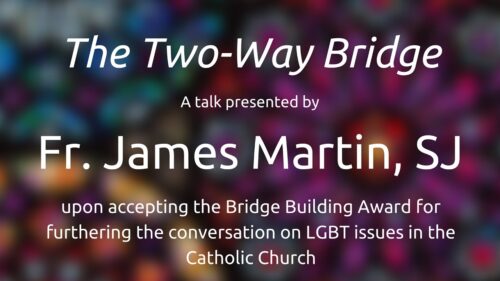

Father Martin has described LGBTQ people in the church as being treated like modern-day lepers, “mocked, insulted, excluded, condemned or singled out for critique, either privately or from the pulpit.” Rather than promoting a culture of life, the church fosters a culture of shame and suffering. Who will rescue the church from this body of death?

In a 2015 study, LGB youth were nearly five times more likely to attempt suicide in the prior year than their heterosexual peers.

Following the thought of Comblin and Sobrino, queer liberation theology posits that salvation can be found among the church’s queer members—that is, where most Catholics least expect it.

To put a queer spin on Comblin’s writing:

The church speaks of queer people always in negative terms, as those who are intrinsically disordered, those who suffer from a “condition,” those who reject God’s plan for human sexuality and gender identity. Seen from outside, the world of LGBTQ people is pure negativity.

Seen from within, however, the world of queer folks has vitality; they struggle to build a world where everyone can flourish, they create their own families and communities, and they grow in intimate relationships not based on ideological theories of sexual and gender complementarity, but on genuine affection, self-sacrifice, and mutual care. They create a joyful culture of solidarity and affirmation—one grounded in pride and the celebration of God-given desires and gifts.

Countless queer Christians and theologians have written on the joy and gifts that queer people bring to the church, but perhaps none so eloquently as Elizabeth Edman, an Episcopalian priest, lesbian and political organizer. In her autobiographical work, Queer Virtue, Edman argues that the “queer moral center… is not only not at odds with core tenets of Judeo-Christian belief, but it is resonant with and in fact points to the most important, challenging, and vivifying aspects of the Judeo-Christian tradition.”

She finds queer habits of “spiritual discernment, rigorous self-assessment, honesty, courage, material risk, dedication to community life and care for the marginalized and oppressed” to be especially prevalent—and prophetic—ways of life.

According to Edman, these practices are demanding expressions of Christianity, not compromises with sinful culture or fallen human nature. Rather than undermining the Gospel, queer folks embody the heart of Christian faith and challenge others to do the same.

Like Sobrino, Edman finds hope for Christian liberation (in her case, from queerphobia) among the People of God who have been relegated to the church’s peripheries. To find salvation, church leaders must learn from them.

Indeed, queer believers know the way out of queerphobia because many of them have escaped it themselves. The prayer, discernment and struggle needed to reconcile LGBTQ sexualities and/or gender identities with Catholicism builds strong faiths and resilient communities. Queer Christians are passionate evangelists committed to sharing the Gospel.

Out @ St. Paul, the New York-based LGBTQ Catholic ministry that I’ve been a part of at the Church of Saint Paul the Apostle, has brought many back to Catholic faith. Friends are always welcoming newcomers into the community. LGBTQ believers create kinship groups to welcome those rejected by parishes and biological families and drive local and global social movements that save LGBTQ lives.

Queer spirituality draws strength from the God of Christian revelation who lovingly creates each person in the Imago Dei and wills for the emotional, relational and spiritual flourishing of all God’s creatures.

Rather than undermining the Gospel, queer folks embody the heart of Christian faith and challenge others to do the same.

In light of their experiences, LGBTQ Catholics also reimagine Catholic theology. Here I remember Dignity. In 1970, three years prior to the American Psychiatric Association’s decision to de-pathologize homosexuality, the group’s first constitution pushed for an evolution in the church’s moral teaching and theological anthropology, contending that “homosexuality is a natural variation on the use of sex.”

Gays and lesbians, like everyone else—possessed a natural right to “responsible and fulfilling” sexual intimacy that could be exercised “with a sense of pride.”

Since then, with the help of theologians such as John McNeill and Mary Hunt, Dignity has responded to every major development in official Catholic theology on LGBTQ issues with its own articulations of faith and practice. These statements are a treasure for queer Catholics and allies today.

Queer faith is good news for the church because it opens space for personal growth and collective transformation. With LGBTQ Catholics active in the church, the Body of Christ is not doomed to repeat the mistakes of its past. As the Body of Christ searches for new, healthy ways of relating to LGBTQ people, it will only succeed if it watches and learns from those who have been reflecting on God’s work for generations.