Editor’s note: This is the final part of a three-part series by the Rev. William Hart McNichols. Click here for parts one and two.

Part III

At my home in New York, I found out that some members of my Jesuit community were uncomfortable with me living there while I ministered to critically ill H.I.V./AIDS patients. They were afraid I’d bring AIDS into the house through my daily contact with the dying. People did not know for sure how the disease was transmitted and so I began to look for another community.

Somehow, I was invited to St. Ignatius Retreat House on Long Island, in Manhasset. I had a meeting with the Jesuit superior there, and he invited me to come live at the magical “Inisfada,” a Tudor-revival mansion that once belonged to an American-born papal duke and his wife before they willed it to the Jesuits in the late 1930s. (The house was torn down in 2013.)

The night I moved in, I saw a beautiful halo around the moon. In Catholic symbolism, Mary is the moon, the reflected light of the Son. It was in my basement room in Manhasset that I began to design my first painting about AIDS, called “The Epiphany: Wisemen Bring Gifts to the Child.”

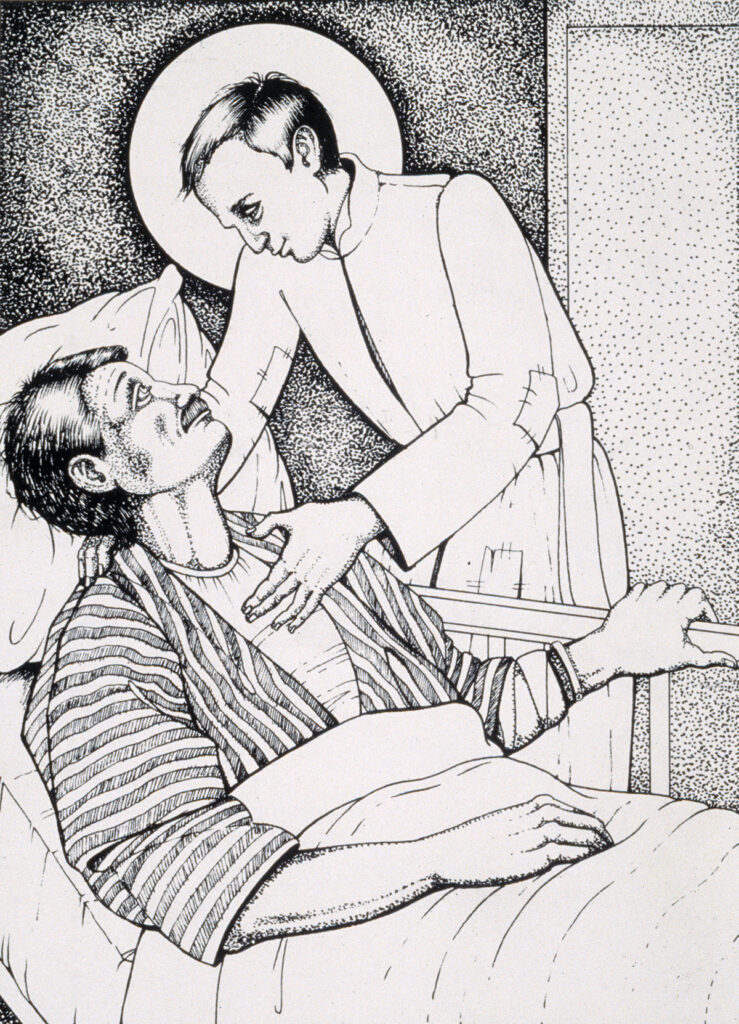

In a bulletin of the Missouri Jesuit Province, I had seen a photo of a Pierre Le Gros the Younger sculpture depicting the Jesuit Saint Aloysius Gonzaga carrying a man dying of the plague. This hit hard. I began to learn everything possible about St. Aloysius and found out he was not at all what people thought of him.

He called himself “a piece of twisted iron” that needed to be twisted upright. No one really believed him because he was so advanced spiritually, but after reading a history of the affluent and influential Gonzaga dynasty, I believed him. He became, along with Saint Francis, my patron.

I felt his presence all the time. I’d take AIDS patients, who were still able to travel, to New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art to visit the Italian saint, depicted in the massive painting, “The Vocation of Saint Aloysius (Luigi) Gonzaga,” by the 17th-century Baroque artist Guercino.

I began a watercolor-and-gouache painting using the first two patients I had visited. There was St. Francis of Assisi holding the gay man being administered droplets of orange juice by his lover, and there was St. Aloysius holding another young, heterosexual man who had contracted AIDS through a needle infection. Over St. Francis is a glowing ring of the Crown of Thorns, with signs of hope, called wishbones, falling down upon them. Over St. Aloysius are three lilies, Catholic symbols of purity, in flames; we all become purified through fire.

I wanted to find a Virgin Mary that wasn’t white or wearing white. I chose the lushly-garmented Our Lady of Guadalupe. She wears a turquoise outer cloak, studded with stars, and a salmon-colored robe. On her lap is the Santo Nino, or Holy Child. He’s like one of those kids who reaches out to everyone, not knowing who is good, indifferent or bad. He just wants to hug everyone. My experience with AIDS patients was that they felt the adult Jesus was angry or judgmental towards them. So I’d tell them: Why not hold the Baby Jesus and talk to Him? This was hilarious to them—and yet they’d try.

When the Franciscans made holy cards of my painting, I didn’t have to use convincing words anymore. I never wore clerical garb when visiting a patient because I knew I wouldn’t get past their hospital door. I wore a suitcoat with a large button of Saint Anthony holding the Infant Jesus, which would get me into the room long enough to help people feel that I wasn’t a danger.

My experience with AIDS patients was that they felt the adult Jesus was angry or judgmental towards them. So I’d tell them: “Why not hold the Baby Jesus and talk to Him?”

In my painting, Mary and the Christ Child are on a rainbow throne, flowing out the Book of Revelation, and over the waters of death are bobbing, red vigil lights. This comes from one of my favorite songs, “Clara, Clara,” from the George Gershwin opera, Porgy and Bess.

Clara, Clara / Don’t you be downhearted / Clara, Clara / Don’t you be sad and lonesome / Jesus is walking on the water / Rise up and follow Him home / O Lord, O my Jesus / Rise up and follow Him home

The Franciscans had given me a ground-level office in SoHo, near the Church of St. Anthony of Padua. Sick people would take a cab, meet with me and then go home. It was to thank the Franciscans that, when I wrote my self-published book of poetry, Fire Above/ Water Below, I dedicated it to them.

I have been asked to write about “coming out,” too.

Briefly, I will say that I had my Jesuit provincial’s permission in 1989 to write an essay about my coming-out experience in a book published by New Ways Ministry. However, there wasn’t much need for me to write this story, since people who worked with AIDS patients or celebrated Mass with the LGBTQ Catholic group Dignity were assumed to be gay. I was given the opportunity to write anonymously, but I thought, “Why even write if you’re not going to use your real name? If you’re not who you truly are, then who are you?”

Coming out is never a one-time thing. I keep coming out in every situation I’m in. It has affected my priesthood since I was ordained in 1979. I have suffered a lot of abuse in my ministry, and the worst persecution and abuse has always come, unsurprisingly, from closeted LGBTQ people. But I have also received plenteous, abundant graces.

Whatever suffering I have experienced or witnessed has been channeled into my images and icons. A wise older priest-mentor once told me, right before my ordination, “The best thing you can do for the gay community is to be a healthy, continually creative, compassionate, openly gay man.” I’ve tried to do this for 43 years. And I have been given the gratuitous grace to never give up on myself or the Holy Church, as Saint Julian of Norwich calls her.

For more information on the life and ministry of Father McNichols, you can view the 2016 documentary film “The Boy Who Found Gold” or listen to his interview with America magazine national correspondent Michael O’Loughlin on the podcast, “Plague: Untold Stories of AIDS and the Catholic Church.”