This essay first appeared in our weekly Scripture reflection newsletter on November 9, 2024.

I’m no Greek scholar. But I know a little Greek, thanks to a course I took during my Jesuit philosophy studies at Loyola University Chicago, as well as some private tutoring with the New Testament scholar Wendy Cotter, C.S.J., who kindly taught me New Testament Greek at her kitchen table for a semester. And few things were as exciting to me as when Sister Wendy (or Professor Cotter) helped me parse out the first few words of John’s Gospel: “In..the…beginning…was…the Word.”

But I “have” (as scholars say) enough Greek to help me understand the Gospels a little better and work my way through the various interlinear translations and some Bible commentaries. And it always helps to go back to the original words, phrases and sentences, to see what might have been lost in the translation. Or, just as often, to see what can be added to our understanding of the English-language texts. In short, those two courses at Loyola Chicago, one formal and one informal, were well worth it.

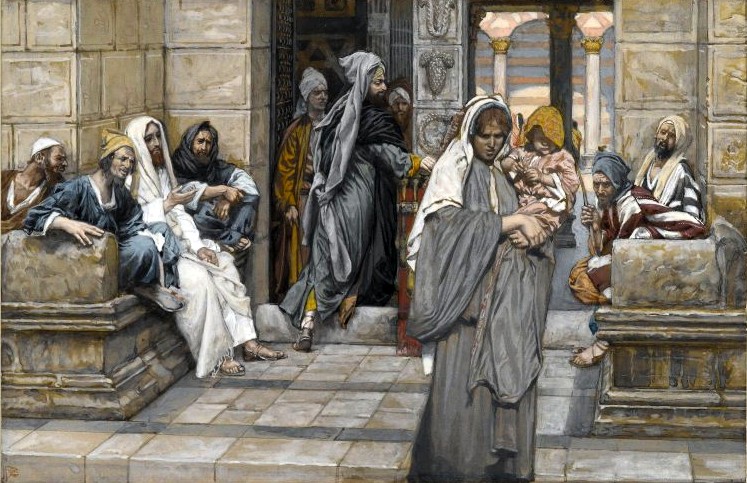

This week’s Gospel is a case in point. It’s the story of the “widow’s mite,” in which Jesus notices “many rich people” donating “large sums” to the Temple treasury in Jerusalem. He also notices a poor widow who puts in “two small coins worth a few cents.” Seeing this, Jesus calls his disciples over and praises the “widow’s mite,” which he esteems as worth more than all the rest since, “They have contributed from their surplus wealth, but she, from her poverty, has contributed all she had, her whole livelihood.”

Another parallel, of course, is the story of Jesus himself, whose radical self-gift and his “pouring out” (kenosis) of himself for the Father, feeds us all. He is the Bread of Life.

The obvious parallel for this kind of self-gift comes in the First Reading, from the First Book of Kings, in which the Prophet Elijah visits a widow in the town of Zarephath. When Elijah asks her for some water and bread, she replies that all she has left is a handful of flour and some oil and after she prepares something for herself and her son, “we shall die.” But when Elijah encourages her, she bakes the cake and finds, as he has prophesied, that the jar of flour does not go empty and the oil does not run dry; and the three are able to eat for a year. Another parallel, of course, is the story of Jesus himself, whose radical self-gift and his “pouring out” (kenosis) of himself for the Father, feeds us all. He is the Bread of Life.

But the main focus of this Sunday’s Gospel story is on what Raymond E. Brown calls in his Introduction to the New Testament, the “genuine religious behavior” of the poor woman, compared with that of the rich people, who seemingly do these things for show.

But that raises an interesting question: How does Jesus know what all these people are putting into the treasury? Is he peering into the collection boxes? Does he somehow intuit? Or does he have some sort of divine knowledge?

Jesus loves whatever little you can give, knows that you’re doing your best and blesses your own small offerings.

Here’s where the original Greek is helpful. Mark’s Gospel uses the word gazophylakion, which scholars think may be a word not simply for the “treasury” but what the Sacra Pagina commentary describes as “trumpet-shaped chests in the sanctuary, each labeled for a different purpose (yearly taxes, bird offerings, etc.).” Thus the coins (chalkon), which were made of copper, would “reverberate when tossed into the trumpet-shaped receptacles and thus draw attention to both the gift and the giver.”

This helps us understand the very public nature of the rich person’s donation: Jesus and the rest of the crowd could hear how much they put in, and the rich people knew it. More touchingly, the poor widow would know how seemingly insignificant the pathetic clink of her two small coins would sound. These were lepta, the smallest denomination of coins possible.

All of us, at various points in our lives, are embarrassed that we seem to have little to give. That goes not only for our money and time, but also for our stores of energy, of hope, of joy. We seem to have so little to give and sometimes it seems that everyone sees it. No matter. Jesus loves whatever little you can give, knows that you’re doing your best and blesses your own small offerings.