This essay first appeared in our weekly Scripture reflection newsletter on November 2, 2024.

There is a moving tradition in the Jesuit Curia, or headquarters, in Rome, where I have been staying for the past few weeks. Once a week, Jesuits from various parts of the world (the Curia is nothing if not international) read out the names of the Jesuits who have died in the past week. There is also an ancient bulletin board where death notices are posted from the Jesuit provinces around the world. A few days ago, I was sorry to hear the name “John R. Donahue” read out, along with his age at the time of his death—91—and the number of years he has been in the Society of Jesus, an amazing 73 years.

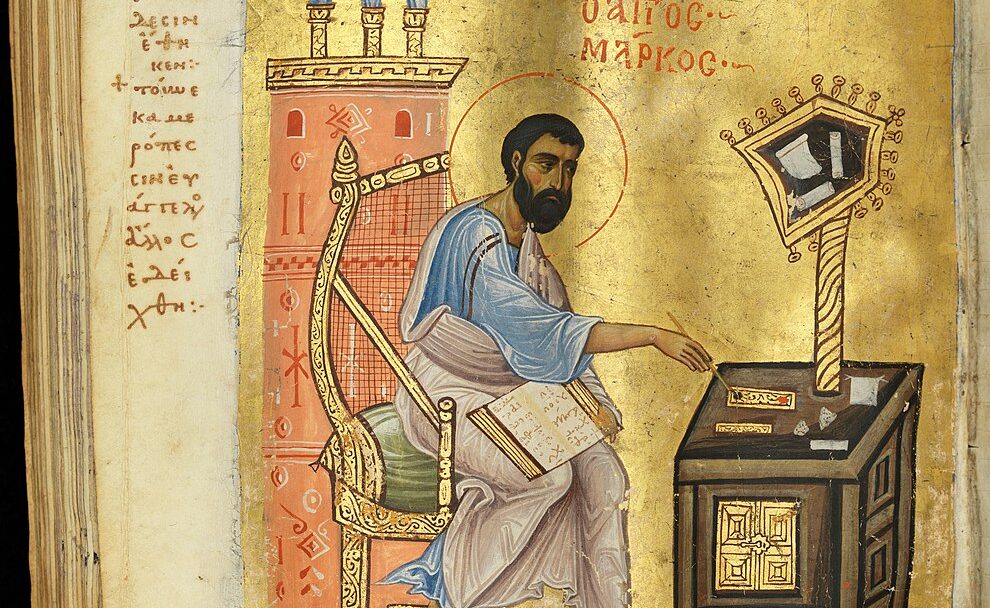

Father Donahue, as those who read these reflections might know, was an esteemed New Testament scholar and one of the editors, along with Daniel J. Harrington, S.J., of the Sacra Pagina commentary on the Gospel of Mark. He was also the author of many books and scholarly articles and had a particular interest in the parables, as evidenced by his fascinating book The Gospel in Parable: Metaphor, Narrative and Theology in the Synoptic Gospels. His scholarship helped me immeasurably and he was a gracious reader of several of my books. And not long ago he penned a beautiful article for Outreach.

This Sunday we’re not reading a parable, but a nonetheless essential passage from the Gospel of Mark—Jesus’ giving of the “Great Commandment.” And this is where a good Bible commentary can prove especially helpful: enabling us to see something new about even the most familiar passages.

This is where a good Bible commentary can prove especially helpful: enabling us to see something new about even the most familiar passages.

In this 12th chapter of Mark, “one of the scribes” asks Jesus which is the first of the Commandments. Jesus answers that the first is the Shema (“Hear O Israel: The Lord God is Lord alone…”) and the second is “You shall love your neighbor as yourself.” The scribe approves of his answer, which prompts Jesus to praise him and silences the crowd.

Is there anything new we can learn about this familiar passage? Well, one thing to avoid when reflecting on Jesus’s interactions with the scribes and Pharisees is the notion that Jesus was somehow rejecting Judaism. (This is the overarching thesis of Amy-Jill Levine’s superb book The Misunderstood Jew.) In their commentary on this Markan passage, Father Donahue and Father Harrington caution against that misinterpretation by reminding us that this narrative should not be seen as a “controversy or conflict story as it is a conversation between a teacher and a student.” Moreover, they write:

In a Palestinian Jewish context, it is unlikely that Jesus’s double love commandment would have been intended or understood as abrogating the rest of the Torah. Rather, its function would have been to simplify and facilitate the observance of all the commandments in the Torah. By emphasizing inner dispositions (love of God and neighbor) and by going to the root of all the commandments, Jesus provides a help and a guide to doing God’s will as revealed in the Torah.

By emphasizing inner dispositions (love of God and neighbor) and by going to the root of all the commandments, Jesus provides a help and a guide to doing God’s will as revealed in the Torah.

There is a strange tendency today, in some Catholic circles, to want to set aside New Testament scholarship, because it will somehow challenge a person’s faith or lead one to reject the truth of the Gospels. But Catholic scholars like Fathers Harrington and Donahue, whose whole lives revolved around the New Testament, spent years—decades—delving into the historical background of the Gospels, how the texts were edited, how the various passages fit together and even the meaning of the individual words. Good biblical scholarship helps us to more fully understand Jesus, the man who Father Donahue loved, served and studied for all those many years. May he rest in peace.