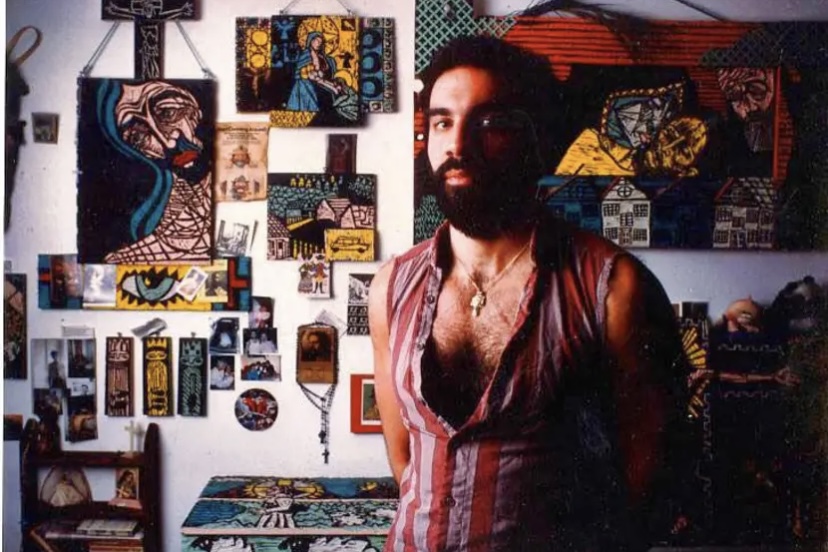

I met Adrian Kellard in 1986. At the time, I was 20 years old, living at the Catholic Worker on the Lower East Side of Manhattan and still in the closet. An openly gay co-worker brought me to meet Adrian as he was setting up his first solo art show at a gallery in SoHo.

Adrian’s artwork blew me away. He etched and carved and painted bright bold colors on wood planks and constructed them into holy images: crucifixes, virgins and saints. Many of his works were altarpieces surrounded in rays and stars and flowers. I saw reflections of Rouault, Van Gogh, Michelangelo, Giotto.

Many of the sacred images, particularly those of Christ, were at once muscular and tender; the feeling they conveyed was both devotional and nakedly homoerotic. Walking into that gallery felt like crossing into the threshold of an extraordinary church, one where queerness and devotion were fused together.

To witness a lover of God who fully accepted his queerness helped me find the courage to likewise accept myself.

Adrian was no less striking than his art. When I first saw him, he was up on a ladder, wearing big black combat boots, tight khaki pants and a white T-shirt. His dark hair was shaved to stubble on the sides with a wide, low mohawk on top. He had a thick goatee and big, muscular arms covered in tattoos—Saint George slaying the dragon, a crucifix drawn by Michelangelo, a fiery Sacred Heart and the prayer “Kyrie Eleison.” Adrian looked like a big, butch, gay Catholic skinhead. I had never imagined such a person could even exist.

I was more than slightly intimidated to meet Adrian, but after he came down from the ladder to shake my hand, I was disarmed by a sweetness and vulnerability that belied his rough appearance.

Meeting Adrian inspired me profoundly. He clearly believed in a God whose love was deeper and more inclusive than I’d allowed myself to imagine, a God whose burning love and compassion embraced queer people. To witness a lover of God who fully accepted his queerness helped me find the courage to likewise accept myself.

The next years would be difficult for Adrian. He was diagnosed with H.I.V. in a time when the disease was an almost certain death sentence. Many of his friends suffered excruciating deaths, and Adrian often attended funerals weekly. But he also joined the radical direct action group Act Up, aligning himself with their efforts to secure medical treatment and promote H.I.V. prevention measures.

“I believe [Jesus] died and was buried and rose on the third day. My art is about my faith in the Resurrection. I believe in the risen Christ.”

As a Roman Catholic, Adrian contended with the fact that his local bishop, Cardinal John J. O’Connor of New York, fought tooth and nail against interventions to protect people from H.I.V. infection. The cardinal strenuously sought to prevent safe-sex information from being taught in the public school system, as well as in any local Catholic institutions; he sought to discredit the efficacy of condom usage as a means of protection. Among the city’s LGBTQ community, he was seen as H.I.V.’s most powerful facilitator.

Unfortunately, Cardinal O’Connor was not alone. Church leadership, in opposing the use of condoms, sent a message to LGBTQ people they valued tradition and dogma over their lives, as well as the lives anyone having sex outside of marriage.

The church issued increasingly strident condemnations of self-accepting queer people, exemplified by Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger (later Pope Benedict XVI) in his infamous 1986 “Halloween letter,” which described same-sex desires as ordered towards “an intrinsic moral evil,” and the ejection of Dignity from Catholic parishes shortly thereafter. It was a dreadfully demoralizing, heartbreaking time to be a queer Catholic.

A year or so after Adrian was diagnosed with H.I.V., I went to see him speak at New York University as part of a panel of artists who incorporated Catholic motifs in their work. The other artists spoke of kitsch and postmodern irony as they showed slide screen examples of their creations. There was no sense that those artists saw their use of Catholic imagery as anything but a means to convey ideas having little to do with faith or the love of God.

Adrian occupied an entirely different realm. As Adrian showed his religious images, as well as newer artworks that clearly grappled with AIDS, he spoke of how he wanted his work to be a witness to his belief.

“I believe in Jesus,” he said forcefully with his Italian-Irish New York accent. “I believe he died and was buried and rose on the third day. My art is about my faith in the Resurrection. I believe in the risen Christ.”

Under the fluorescent lights of that white-bread, academic setting, standing there in front of his peers—all the while knowing H.I.V. was lurking in his blood, waiting to destroy him—Adrian offered among the clearest, strongest, most moving professions of faith I have ever witnessed in my life. It felt like seeing Saint Paul proclaiming the risen Christ on the streets of Ephesus. I marveled at his ability to cling to the heart of his faith during a time of cruelty and condemnation.

The evidence of that clinging was in his art. Overwhelmingly, they were images that affirmed a God of tenderness and love. I think of his Lovers, which combines a depiction of the crucified Christ above an image of Jesus clasping the Beloved Disciple against his breast. The disciple is obviously a self-portrait of Adrian.

Thérèse remained by his side through the frightening procedure, saying not a word, simply offering a smile of kindness and compassion.

Another self-portrait is found in Adrian’s masterpiece The Promise—a large carved wooden panel, upon which he painted a solemn, sorrowful image of Saint Christopher (looking like a young Adrian) carrying a dark-skinned, immensely sad Christ Child. They pass through a dark background ringed with stars. Gazing upon them is the macabre skeleton of death. Alongside them the words: I will never leave you.

I become overwhelmed when I contemplate The Promise. Considering how Adrian was approaching death, while contending with rejection and condemnation from a faith that should have offered consolation, it strikes me as a heroic affirmation of a loving God, a burst of hope coming from the brink of despair. How fitting that his final solo show, in 1990, was titled Unconditional Love.

In 1991, a few months before Adrian died, my partner Gary went to visit him. Adrian described a remarkable experience he’d recently had.

Adrian had been at a medical clinic. He was by himself in a room, waiting to undergo a bronchoscopy. This was a painful and frightening rite of passage for many people with AIDS. A long tube with a small, illuminated camera at the end was inserted into the patient’s mouth and pushed into the lungs. It helped diagnose a type of pneumonia commonly found in people with suppressed immune systems. The patient, while lightly sedated, was kept awake for the procedure.

Adrian was filled with anxiety at the prospect of having so long and sinister a device snaking through his body. While fighting the urge to bolt out of the room, Adrian saw the door open, and in walked Saint Thérèse of Lisieux. Thérèse, the 19th century Carmelite nun who died of tuberculosis at age 24, approached Adrian and took his hand in hers.

She remained by his side through the frightening procedure, saying not a word, simply offering a smile of kindness and compassion. Her presence calmed and consoled Adrian through the ordeal. When the bronchoscopy was finished, Thérèse gave Adrian a final smile and left the room.

“Here’s the crazy thing,” Adrian marveled to Gary, “I was never into Saint Thérèse. I was always a Saint Anthony man!”

I can only speculate as to the meaning of Adrian’s experience. Nonetheless, I find it immensely moving. Like Adrian, Thérèse’s faith became a struggle in her last years. I cannot imagine her ever perceiving church leaders as cruel and callous, as did Adrian. Instead, Thérèse’s struggle was with belief in eternal life. For her final two years, she was plagued by an inner voice that whispered her hope for eternal life was an illusion, that all that awaited her beyond the grave was “a night of nothingness.”

At a time when he felt rejected by the church, I am immensely grateful for Adrian’s experience of Thérèse’s consoling presence.

But she did not give in to despair. On the advice of her confessor, she wrote out the Apostles’ Creed in her blood. Thérèse understood her mysterious call to radical solidarity with those in despair. As she put it, she would “eat the bread of sorrow at the table where the poor sinners eat.” Even on her deathbed, describing the inner darkness she found herself in, she confessed: “Everything has disappeared on me, and I am left with love alone.”

Adrian, too, was left with love alone. At a time when he felt rejected by the church, I am immensely grateful for his experience of Thérèse’s consoling presence. She wrote: “At the heart of the church, my vocation is love.” How wonderful that Adrian was able to experience her love as he struggled with terrors and bitter disappointments.

On this your feast day, beloved Saint Thérèse, I pray in thanksgiving for your kindness to my friend Adrian. And I ask, through your intercession, that our church may become an ever-clearer witness to God’s unconditional love for all her children.