This essay first appeared in our weekly Scripture reflection newsletter on June 28, 2025.

In today’s Gospel, Jesus and his disciples are on the way to Caesarea Philippi when Jesus asks the disciples an odd question: “Who do the people say that the Son of Man is?” It’s a canny approach. He’s probably overhead the disciples trying to figure out, or even arguing about, who their leader really was.

At first, however, Jesus avoids asking them directly, perhaps wanting to spare them from the embarrassment of giving a wrong answer. So he poses it indirectly: Who do other people say that I am?

In response, they offer what is probably a fair summary of the “general consensus” in Galilee and Judea at the time. Jesus might be John the Baptist come back to life (which made some sense, since Jesus seems to be echoing some of John’s themes and may have been a disciple of the Baptist for a time); Elijah (who, in a sense, presaged Jesus’ ministry with a miracle of bringing someone back from the dead and performing a “food miracle”); or Jeremiah or another prophet (which made sense, since Jesus had already clearly shown himself as a prophet).

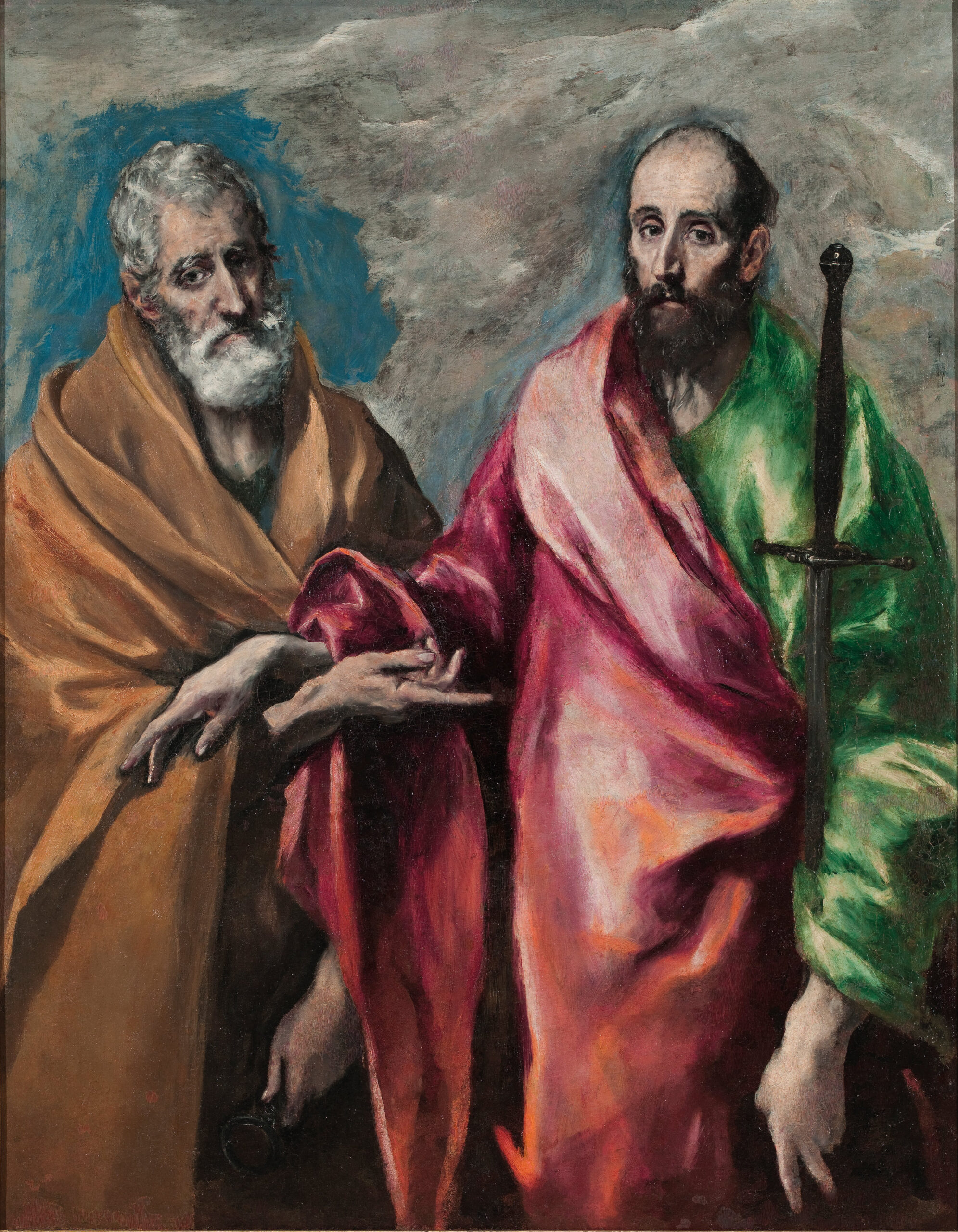

In many ways we are luckier than even St. Peter, who beheld Jesus face-to-face; or St. Paul, who heard him in a vision.

Then Jesus directs the question to them: “Who do you say that I am?” Peter, typically, is the bold one here, answering that he is the Christ (the Christos, or Anointed One), that is, the Messiah. Thus, Jesus is far more than John the Baptist, Elijah and Jeremiah. Jesus praises Peter for his answer, identifying it as coming from the Father, and then renames Simon as Peter (in Aramaic Cephas, or rock; in Latin Petros).

But many New Testament scholars point out that even Peter’s inspired answer doesn’t fully capture who Jesus is: the Second Person of the Trinity. People’s notions of who the Messiah was going to be varied widely in first-century Judaism. (Amy-Jill Levine’s book The Misunderstood Jew is especially good on this.) Overall, though, Jesus exceeds any of Peter’s categories.

Now, modern-day Christians have the benefit—thanks to knowing the whole story, knowing about the Resurrection and the church’s tradition—of understanding who Jesus is, even if we cannot fully comprehend the mystery of the Incarnation. So, in many ways we are luckier than even St. Peter, who beheld Jesus face-to-face; or St. Paul, who heard him in a vision.

In many ways, though, we are very much like St. Peter in that we also have to reflect on our experiences of Jesus to understand him. St. Paul, you could also say, was in that same “boat” (to use a Petrine image) as well. When he first beheld Jesus during his vision on the way to Damascus, he had to ask, “Who are you?” Of course, he received an answer immediately: “I am Jesus, whom you are persecuting” (Act 9:5). But for the rest of his life, he would reflect on that question: “Who are you?”

We do not know Jesus fully—and never will until we see him “face-to-face” in heaven. Until then, we are invited to know him the best we can, and, as St. Peter and Paul did, to experience him.

We are, then, like both Peter and Paul. While we know that Jesus is the Son of God, the Messiah and the Second Person of the Trinity, we do not know him fully—and never will until we see him “face-to-face” in heaven. Until then, we are invited to know Jesus the best we can, and, as St. Peter and Paul did, to experience him.

Peter was finally able to proclaim that Jesus was the Messiah because he had spent time with him. He saw his miracles, he heard his preaching, he took the measure of Jesus. St. Paul came to know Jesus not simply through his initial vision, but by finding him among the community. We can come to know Jesus through the sacraments, through prayer, through reading and study, and also through other people. It’s a lifelong journey of continued encounter with him, as the sacraments, especially the Eucharist, reveal Jesus to us; prayer reveals him; reading and study reveal him; and other people reveal him.

What a wonderful invitation we are given as Christians! Answering the question “Who are you?” will always be an incomplete process; he will always be, in some way, a mystery. But the question that Jesus poses to the disciples—Who do you say that I am?—may be the most important question of our lives.