It was in the early 1960s that I entered my teenage years and first noticed the sexual attraction that I felt for men. But, strong as it was, I had no words to describe my feelings—other than that they were sinful. My parish elementary school in the Bronx provided no sex education, and the Catholic boys’ high school I attended devoted one measly week of biology class to lectures on “human reproduction.”

Then, in one of my English classes, my Jesuit teacher recommended that I write my class report on James Baldwin’s novel, Another Country. Reading it gave me a word to describe my feelings: homosexuality. In the characters that Baldwin created, I saw love and passion between men expressed for the first time. That book set me on a path of self-acceptance.

In the mid-1970s, as a graduate student in history at Columbia University, I decided to write a dissertation on what I then described as “gay” history. I believed that spreading knowledge of LGBTQ history could be an asset in the emerging liberation movement. I tried to imagine what it would be like for students to have LGBTQ historical figures and events integrated into a U.S. history course. In 1983, I began teaching U.S. history at the University of North Carolina at Greensboro. Having lived my entire life in New York City, with its growing and visible LGBTQ activist movement and community, I now found myself in the North Carolina Piedmont, where such a movement barely existed. Virtually none of my students had ever encountered an LGBTQ person before, or were aware that such people existed.

I tried to imagine what it would be like for students to have LGBTQ historical figures and events integrated into a U.S. history course.

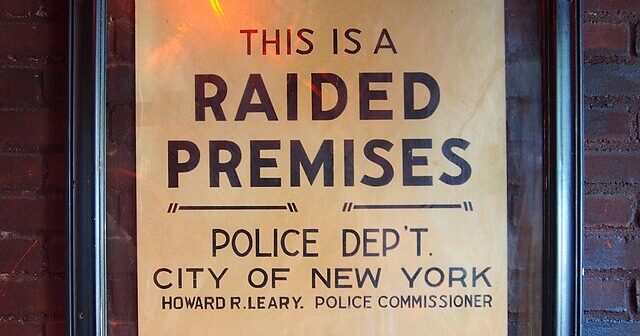

In these years when LGBTQ history was still in its infancy, I attempted to find places where I could integrate it into the courses I was teaching. In the U.S. history survey course, I talked about Jane Addams and other leading women of the Progressive Era settlement house movement, how they had intimate relationships with other women, and how this sustained their activist work for social justice. When we reached the Cold War era, I described the “lavender scare” that occurred alongside the Red Scare, with federal and local governments targeting large numbers of LGBTQ people. Many thousands lost their jobs, were dishonorably discharged from the military and faced arrest by police for simply being at a gay bar. As we moved through the 1960s and its protest movements, I included the Stonewall Uprising and the birth of gay liberation. These were stories my students had never heard before.

Over time, as word about my identity and the content of my classes spread among students, I began to find that some LGBTQ students were enrolling in my courses. They visited me during my office hours to talk about the class, but then shifted the topic to describe their own struggles around their identity. I always listened, encouraged them to keep talking, and without giving advice, assured them that they would find their path.

These were stories my students had never heard before.

I will always remember one moment in a special one-time course on “the politics of sexuality” that I offered in U.N.C.G.’s Residential College, an experimental division of the school where students living in a dorm together took courses that were designed just for them. The last segment focused on the LGBTQ activism that exploded in the wake of the Stonewall Uprising, and I assigned many activists’ political manifestos. As a writing assignment for that unit, my syllabus specified that they compose a “coming out” letter to their parents.

The week that the letter was due, when I arrived in class a student immediately raised her hand and asked, “do we have to mail these letters?” The question surprised me but, before I could answer, another student asked, “what if my roommate sees the letter?” Another immediately responded “my roommate did see the letter!” Comments like these continued until, suddenly, one student shouted, “oh my God! I get it! Can you imagine what it would be like if we really did send such a letter to our parents? This is what gay people experience when they come out. It’s a brave and scary thing to do!”

Perhaps the most touching moment came when I received a letter from the mother of a student, Doug, who took my classes and was brave enough to come out in class during one of our discussions. She invited me to attend his graduation party and wrote, “You have had a profound impact on our son’s life.” When I went to the party, I noticed that I was the only faculty member in attendance and that Doug was there with his partner. I could see the real-life impact of learning and teaching LGBTQ history, just as I had imagined back at Columbia.

We are living in a time when the freedom to teach the true content of history is being challenged across the nation at all levels.

We are living in a time when the freedom to teach the true content of history is being challenged across the nation at all levels. I cannot overemphasize the importance of simply teaching the truth of our nation’s history—its events and its people—because of the impact it can have in moving people toward self-acceptance, pride and a better understanding of each other.