If you’re an alum of Loyola Marymount University in Los Angeles, the number “44” has special resonance: It was retired in 2000 by the men’s basketball team in honor of Hank Gathers, the All-American who led the Loyola Marymount Lions to glory before tragically dying during a game in 1990.

But Gathers wasn’t the first L.M.U. sports legend to wear “44”—and he’s not the school’s only All-American whose accomplishments led to the number being retired. Go out to George C. Page Stadium at L.M.U. and look at the outfield fence. There’s another #44 there: Billy Bean.

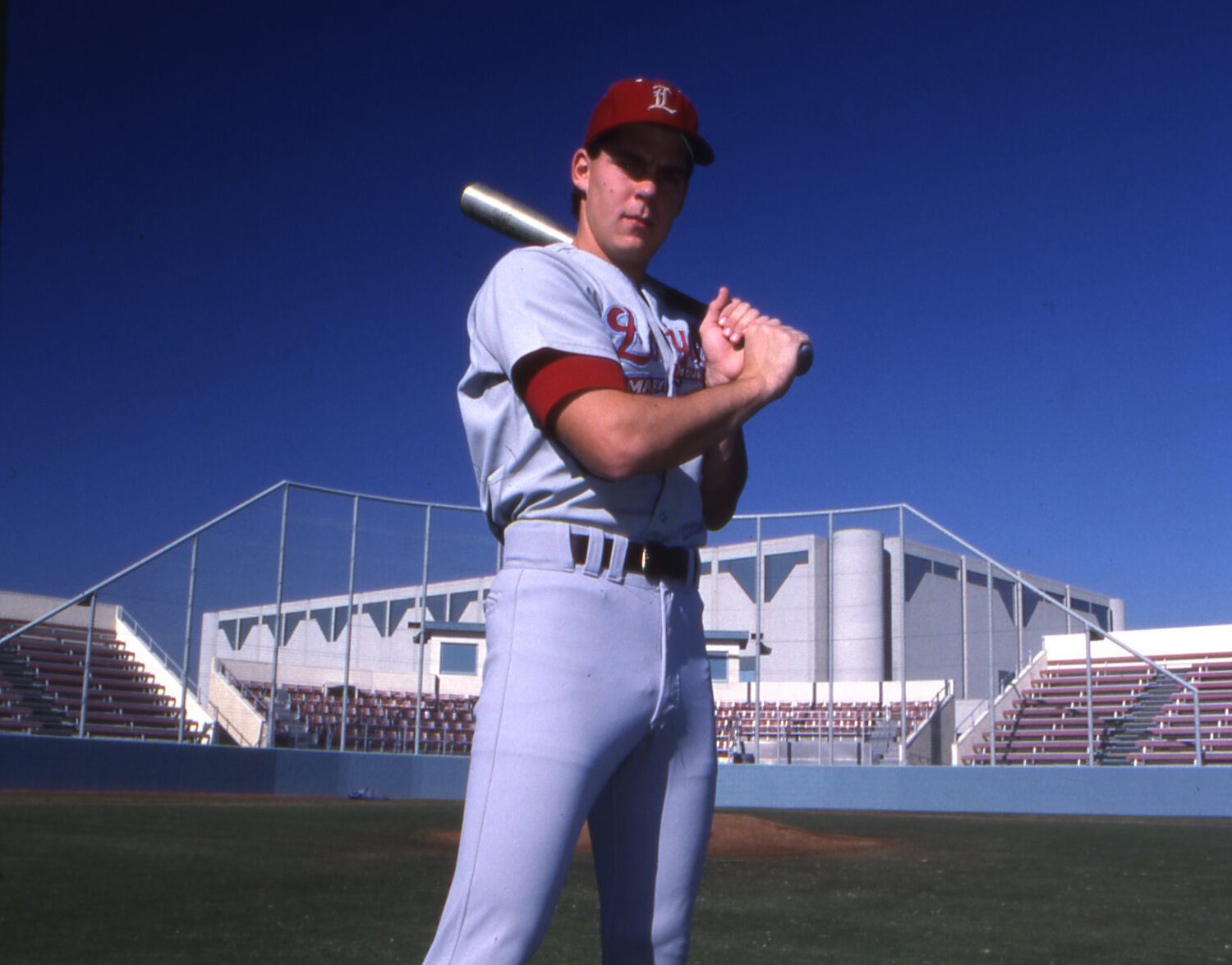

Bean, who died on Aug. 6 of leukemia, led the 1986 L.M.U. men’s baseball team to the College World Series in a remarkable season which saw the Lions ranked #1 in the country for several weeks. Drafted after both his junior and senior seasons, Bean went on to play major league baseball for the Detroit Tigers, the Los Angeles Dodgers and the San Diego Padres, retiring in 1995.

No active major league baseball player has ever come out as gay.

He published an autobiography in 2003, Going the Other Way: Lessons From a Life In and Out of Major-League Baseball. In that book, he wrote more extensively of his decision in 1999 to tell the world a secret that some of his friends and family already knew: He was gay.

Only one former major league baseball player—Glenn Burke in 1982—had ever come out as gay before Bean. Only one other—T. J. House in 2022—has since. No active major league baseball player has ever done so.

Baseball clubhouses can be profoundly homophobic workplaces, and several former players and club officials noted in the many obituaries and tributes to Bean after his death that every baseball locker room has “unwritten rules.” When those rules are broken, players can be ostracized forever.

Of course, both the N.B.A. and the N.F.L.—leagues with their own unwritten rules and that also have a history of homophobic behavior by players and coaches—have seen active and former players alike go public about their homosexuality. Why has baseball proved less amenable to athletes coming out?

In recent years, baseball officials seem to have recognized the problem—and Bean was part of their early efforts at addressing it. In 2014, M.L.B. hired Bean (not to be confused with Billy Beane, the former executive vice president of the Oakland Athletics) as its first “ambassador for inclusion” and promoted him to vice president and special assistant to the commissioner in March 2017; his job eventually morphed into a position as a senior vice president of diversity, equity and inclusion.

One of Bean’s roles in those years was working with players on questions around bullying or homophobia in the locker room. He found his own history as a baseball player helpful in bridging divides with active players.

In recent years, baseball officials seem to have recognized the problem—and Bean was part of their early efforts at addressing it.

“I talk about the fact that, regardless of differences between us, we have shared values about baseball: respect for our sport and the responsibility that goes with being a player,” Bean told LMU Magazine editor Joseph Wakelee-Lynch in a 2016 interview.

“It’s interesting: Few people understand what it’s like to be the only gay person in a room—especially one with a bunch of young male, millionaire athletes—and to talk about your private life. But for the first time, players are discussing these issues with a former player. For that, I give MLB Commissioner Rob Manfred great credit. He said over and over: It’s different when a peer or a colleague is sharing a message.”

Bean was born in 1964 in Santa Ana, Calif., a suburban community in Orange County. The valedictorian of Santa Ana High School in his senior year, he also won a state title in baseball. He attended L.M.U. (full disclosure: my own alma mater) on an athletic scholarship and was twice named an All-American. Drafted by the New York Yankees after his junior year, he chose to stay for his senior year, graduating in 1986 with a degree in Business Administration.

The Detroit Tigers drafted him in 1986. Within the year, Bean was in the big leagues. In his first appearance, he got four hits, tying a major league record.

In stints with the Tigers, Dodgers and Padres (as well as overseas in Japan and back in the minor leagues), Bean earned a reputation as an aggressive, hard-nosed player, but could never break permanently into a starting lineup. He retired after his 1995 season with the Padres.

“I thought because I was gay that my own school would not want my name on any wall. It was a very emotional moment.”

The death of a partner due to complications from AIDS earlier that year played a part in his decision to retire, Bean later told reporters.

Throughout his time in the major leagues, Bean felt the pressure of keeping his sexuality a secret, to the extent it affected his life in other ways. Married in his 20s to his longtime girlfriend, he kept the reality of his homosexuality from others even as their marriage foundered after a few years.

“I was my own worst enemy as a big leaguer. I didn’t believe a gay person belonged in the big leagues, and I really, really tortured myself with a lot of self-hate and shame,” Bean told Chris Benis of the Los Angeles Loyolan, the L.M.U. student newspaper, in a 2024 interview.

When Bean came out of the closet in 1999, in an interview with the Miami Herald, the stakes still seemed high. While some family and friends knew of his sexual orientation by then, he had no idea how his former organizations and teammates—from the pros but also from Loyola Marymount—would take the news.

When L.M.U. retired Bean’s number the next year, it put some of his fears to rest. “It changed my life,” Bean told Wakelee-Lynch. “I thought because I was gay that my own school would not want my name on any wall. It was a very emotional moment.”

Lane Bove, the longtime Vice President of Student Affairs at L.M.U. who retired in 2022 after more than 40 years working at the university, remembered Bean from her time as director of the university’s Learning Resource Center, a tutoring and academic assistance center.

“Billy was a bit of a ‘Mr. Goody-Two-Shoes’ at the time, very smart and the perfect ‘altar boy.’ He kept the other guys in line—he was my ‘adult’ on that team.”

“I worked with all the baseball and basketball players,” Dr. Bove told Outreach in a phone interview. “Billy was a bit of a ‘Mr. Goody-Two-Shoes’ at the time, very smart and the perfect ‘altar boy.’ He kept the other guys in line—he was my ‘adult’ on that team.”

Another close friend and mentor of Bean in his college years was Albert P. Koppes, O.Carm., a Carmelite priest who served two stints at L.M.U. as Academic Vice President. Father Koppes, who died in 2019, had officiated at Bean’s 1989 wedding at the university, and remained close with many of Bean’s former teammates from L.M.U.

In the aftermath of Bean’s public declaration of his sexual orientation, Dr. Bove and Father Koppes reached out. “Al Koppes and I put on a dinner for him” before Bean’s number was retired, Dr. Bove remembered, “and that helped ease him back into L.M.U. He was so appreciative and overcome by that, because it was the first real recognition of him as a gay man at L.M.U. And then after that, he would come back at times to speak to the student-athletes.”

In his 2024 interview with Chris Benis, Bean said that after L.M.U. became one of the first Jesuit institutions in the country to create a university-funded student organization for LGBTQ students in 2015, he made a five-year pledge to financially support the organization.

“Billy said something to me once that has always stuck with me,” Dr. Bove said. “He told me, ‘You know, Lane, I come out every day.’ It was something I had never thought too much about—that gay and lesbian people meet others all the time who they end up ‘having to explain myself’ to. I found that conversation very poignant.”

Bean’s death brought immediate reactions around major league baseball. “Our hearts are broken today as we mourn our dear friend and colleague, Billy Bean, one of the kindest and most respected individuals I have ever known,” said baseball commissioner Robert D. Manfred Jr. in a statement after Bean’s death.

“Billy was a friend to countless people across our game, and he made a difference through his constant dedication to others. He made Baseball a better institution, both on and off the field, by the power of his example, his empathy, his communication skills, his deep relationships inside and outside our sport, and his commitment to doing the right thing.

M.L.B. Commissioner Rob Manfred: “Billy was a friend to countless people across our game, and he made a difference through his constant dedication to others.”

“We are forever grateful for the enduring impact that Billy made on the game he loved, and we will never forget him. On behalf of Major League Baseball, I extend my deepest condolences to Billy’s husband, Greg Baker, and their entire family.”

Bean’s loss will be felt for more than just what he contributed to the sport in the past; he was also a public figure whom M.L.B. surely have hoped would spearhead further efforts toward inclusive clubhouses and organizations.

“Billy Bean made this world a better place, and at the same time, this world is worse off without Billy Bean now. He elevated us with how he lived his life. He made us all better,” Yankees general manager Brian Cashman told the Washington Post. “Therefore, we’re on a better footing because we know a person like that, but we lost a lot at the same time by not having him for what’s to come.”