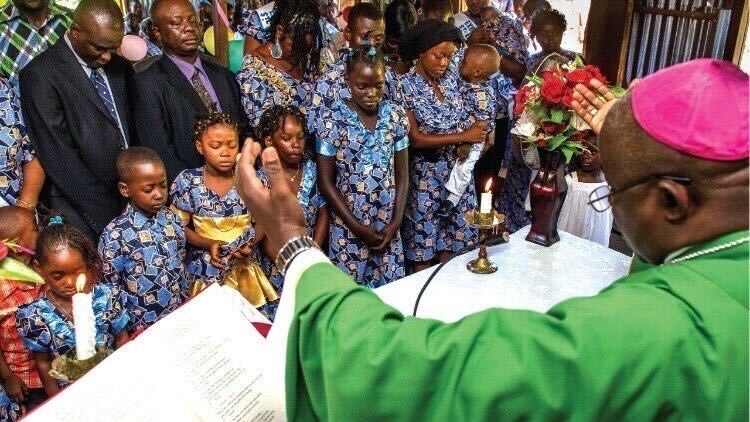

Last week, the Symposium of Episcopal Conferences of Africa and Madagascar (SECAM) issued a statement regarding the declaration “Fiducia Supplicans” (FS), which permits the non-liturgical blessing of same-sex couples and people in irregular marriage situations, under certain circumstance. FS had been occasioned by dubia (questions) submitted to Pope Francis, concerning the role that may be played by LGBTQ people in the life of the church. (The declaration was also approved by the pope.) The SECAM statement, entitled “No Blessings for Homosexual Couples in the African Church,” is a synthesis of the responses of many African episcopal conferences to FS.

In the network of African theologians to which I belong, there was a heated discussion of the Vatican declaration. From this discussion it is evident, at least to me, that in large swathes of Africa, there is an almost neurotic denial that there are African people attracted to members of the same sex. The fact that people of the same sex enter into a permanent, loving, supportive, stable, fruitful relationships is beyond the imagination of many Africans. The very notion runs contrary to what many theologians and pastors claim is African culture.

In large swathes of Africa, there is an almost neurotic denial that there are African people attracted to members of the same sex.

They cite verses from the Christian Scriptures and the church’s tradition to corroborate their abhorrence of the idea. This is, many say, an issue of the Global North. Moreover, they say, it does not occur in Africa. It is irrelevant to us; it is inconceivable that members of a same-sex couple could approach a pastor in Africa, asking for a blessing. And if this were to happen, these couples should be sent away with a stern warning to repent. Finally, goes the thinking, same-sex couples are incapable of receiving God’s blessing because their state of life is sinful and abhorrent to God.

As more theologically educated members of the church, my conversation partners were deeply perturbed by FS. Most understood that the declaration makes no change to the church’s teaching on marriage. But many were concerned by the “slippery slope” argument: If such people receive an informal blessing through the action of an ordained minister of the church, then next they will claim that their relationship is validated by the church. Then the entire edifice of the church’s sexual teaching will be brought into question. We can’t have that, they say.

Some people, especially those with less formal theological education, expressed confusion and sought clarification. Apparently, the language of FS “remains too subtle for simple people to understand,” as the SECAM document stated. This is why the bishops, as pastors in their respective dioceses, countries and episcopal conferences, needed to offer explanations and clarifications to resolve people’s confusion.

While the bishops “insist on the call for conversion for all,” the SECAM statement focuses on the vexed question of blessing persons in a same-sex union.

My hope is that the bishops did this in the spirit of synodality, listening widely, especially to people on the margins of society. Most of those who offered pastoral leadership on the topic stated their fidelity to the papal magisterium, but declared for one reason or another that FS was inapplicable in their diocese, country or conference.

The SECAM statement has gathered and synthesized the clarifications of the various bishops’ and episcopal conferences around the continent. It says that the clarifications of the African episcopal conferences have a common understanding and approach. While the bishops “insist on the call for conversion for all,” the SECAM statement focuses on the vexed question of blessing persons in a same-sex union.

It does not broach the topic of blessing persons in polygamous unions—which are culturally acceptable in some African societies, but which also fall under the purview of FS, as they are “irregular unions.” (As a sign of the importance of this topic in Africa, polygamous unions were discussed in last year’s session of the Synod and mentioned in its synthesis report.)

Nor does SECAM address the practice of couples marrying according to African traditional rites (the so-called “traditional marriage”) or even entering into a legal, civil marriage and living for many years as a couple before having their union ratified in the church. Both of these types of “irregular unions” are technically forbidden by church law and in contravention of scriptural morality.

The statement also provides cultural grounds for the rejection of same-sex unions: African cultures are “deeply rooted in the values of natural law regarding marriage and family.”

“No Blessings” refers to the Catechism of the Catholic Church (2357), and to the 1975 C.D.F. declaration “Persona Humana” (8), stating the “constant teaching of the Church” that describes homosexual acts as “intrinsically disordered.” In support of their position, a large majority of interventions from African bishops also cite Leviticus 18, Genesis 19, Romans 1 and 1 Corinthians 6. One wonders how much hermeneutics or biblical scholarship has been applied in the citation of these texts.

The statement also provides cultural grounds for the rejection of same-sex unions: African cultures are “deeply rooted in the values of natural law regarding marriage and family.” Thus, unions of persons of the same sex are unacceptable because they “are seen as contradictory to cultural norms and intrinsically corrupt.”

“No Blessings” cites many bishops’ fears of exposing themselves to scandal if they were to impart the extra-liturgical blessings proposed by FS. In saying this, they seem to telegraph that they have little appetite for an overly prophetic stance in pastoral care for this group of marginalized persons. They assert that the human rights of same-sex-attracted people should be respected in all circumstances, including in the church.

Certainly, in some countries even declaring oneself to have same-sex attractions is punishable by long-term imprisonment, and in other countries, persons found to be in same-sex relationships are liable to corporal punishment or the death penalty. In other places, LGBTQ people are subject to other forms of violence, beatings and harassment.

Undoubtedly, it will take time for the pastoral inspiration of “Fiducia Supplicans” to become more widely accepted.

In terms of civil law, South Africa is a beacon of light on the African continent. Its progressive 1994 constitution forbids discrimination on the basis of race, religion, language, gender or sexual orientation. Same-sex civil marriages are permitted in the country and same-sex couples are permitted to adopt children who would otherwise have no parents at all. It is little wonder that people from many parts of Africa, whose human rights are not respected in their home countries, seek asylum in South Africa.

For decades South Africa has recognized the refugee status of people who are persecuted or whose lives are endangered because of their sexual orientation. For those who do not try to make it to Europe, South Africa is often a second-best destination. One city parish in the country has a support group for LGBTQ parishioners. It is noteworthy that none of the members of the group are so-called ‘Europeans.’ They all come from African countries.

Published in French, Portuguese and English, the SECAM statement observes that the reception of FS has not been entirely uniform. “Some countries prefer to have more time for the deepening of the Declaration which… offers the possibility of these blessings but does not impose them.” Undoubtedly, it will take time for the pastoral inspiration of FS to become more widely accepted. One hopes that in the meantime it does not die a death of committee work. One also hopes for more prophetic protection of a severely marginalized group on this continent.