For the past several years, Pope Francis has been journeying forward with LGBTQ people, gesturing hospitality through both word and action, rather than with changes in any magisterial teaching. In the last months of 2023, that process seemed to suffer a disillusioning setback (with the conclusion of the first session of the Synod on Synodality in October), followed by a surprising leap ahead in December (with the release of “Fiducia Supplicans,” on blessing people in same-sex unions.)

To understand the significance of these developments, it is helpful not only to clarify “what happened,” but to place events in context.

From almost the beginning of his pontificate, Pope Francis has signaled that LGBTQ people should not be excluded from the circle of Catholic faith and practice—from his famous “Who am I to judge?” comment on gay priests to his personal interactions with gay and transgender people. The ongoing dialogue between the pope and Outreach editor James Martin, S.J., on a less judgmental and more pastoral approach to LGBTQ Catholics, has been well-publicized in Catholic circles.

Pope Francis has signaled that LGBTQ people should not be excluded from the circle of Catholic faith and practice.

Nevertheless, it has been abundantly clear, at least from the time of the 2014 to 2015 sessions of the Synod on the Family, that sex, gender and LGBTQ issues are highly contentious in the worldwide church. Viewpoints in Eastern Europe and in the quickly growing church of the Global South, for example, diverge significantly from attitudes in North America and Western Europe.

While 76 percent of U.S. Catholics want more social acceptance of gay and lesbian unions, large percentages of Catholics elsewhere are willing to back the magisterium—at least on the idea that homosexuality is “disordered,” if not the Catechism’s caveat that LGBTQ people (“homosexuals”) deserve “respect, compassion and sensitivity.”

In Eastern Europe, “roughly half or fewer” of Catholics support LGBTQ acceptance. In Lithuania, for example, 87 percent of Catholics oppose gay marriage. Nigeria (6 percent), Lebanon (14 percent) and Kenya (16 percent) rank near the bottom of the scale of societal support for homosexuality, according to data from the Pew Research Center. In Africa, advocacy for laws criminalizing homosexuality, with some countries imposing the death penalty, is growing. Uganda made homosexuality a crime in 2023, with endorsements from multiple church leaders.

Given the broader picture, and the global character of an episcopal synod, it should not be surprising that currents friendly to LGBTQ inclusion might be rebuffed by oppositional cultural-ecclesial forces. The first session of the Synod on Synodality, like the two-part Synod on the Family, provoked heated debate among bishops from different regions, and resulted in a final document that adhered more to traditional teaching than some had anticipated.

It should not be surprising that currents friendly to LGBTQ inclusion might be rebuffed by oppositional cultural-ecclesial forces.

Yet both Synods saw a more gradual and less uniform unfolding of Catholic teaching that was occurring simultaneously, both during official sessions and after they had ended.

The interim report of the Synod on the Family drew an analogy between marriage and faithful, self-sacrificing same-sex unions (52), but the final relatio struck that comparison down, asserting instead that the two kinds of unions are not even “remotely analogous” (55). On the face of it, a similar fate met LGBTQ aspirations in Pope Francis’ follow-up apostolic exhortation, “Amoris Laetitia,” where marriage and gay unions are in no way “on the same level” (251). But there is an interesting nuance of wording in “Amoris Laetitia,” suggesting that greater pastoral recognition of, and openness to, LGBTQ Catholics, remains a live question.

“Amoris Laetitia” and same-sex unions

In “Amoris Laetitita,” the introductory words—reporting a consensus against the similarity of same-sex unions to marriage—are very different from the wording favoring the inclusion of civilly remarried Catholics.

On remarriage, Pope Francis offers the favorable consensus, then adds “which I support,” and “I am in agreement” (297, 299). But on the incomparability of same-sex partnerships to marital virtues, he merely reports, “the Synod Fathers observed…” (251). The pope seems to claim personal ownership of more open policies toward divorced and remarried Catholics, but not of emphatically exclusionary ones toward gay and lesbian couples, which he provides as the majority opinion.

The pope seems to claim personal ownership of more open policies toward divorced and remarried Catholics.

This difference may reveal something not only about where Pope Francis’ own sympathies lie, but also about the difficulty of leading a divided and fractious church, where more open discussion and empowerment of the “peripheries” has unleashed traditionalist dissent from papal leadership and lately raised the specter of schism.

I hypothesize that avoidance of that outcome might be one motivation behind papal circumspection regarding adjustments of Catholic sexual ethics and theologies of marriage.

The Synod on Synodality

Preparations for the 2023 session of the Synod heightened expectations that Pope Francis’ emerging LGBTQ support would take on a more formal character. The working document for the Synod’s continental stage acknowledged that homosexuality has become a controversial question in many regions (51), and recognized that LGBTQ Catholics “feel a tension between belonging to the Church and their own loving relationships” (39). Then there was the pointed question of the Instrumentum Laboris: “What concrete steps are needed to welcome” groups like “LGBTQ+ people”? (page 30)

Pope Francis himself had signaled potential progress by appointing Father Martin as a Synod delegate. These developments awakened hope that ecclesial openness to LGBTQ Catholics would go beyond papal statements unmet by institutional implementation.

Yet many were “disappointed” by the Synod’s take on LGTBQ Catholics. The Synod report’s non-condemnatory yet minimalist acknowledgment that “identity and sexuality” (in the Italian-language version, “gender identity and sexual orientation”) may have “raised new questions” that Catholic categories have not yet “grasped” (15) is perhaps the report’s greatest understatement.

These developments awakened hope that ecclesial openness to LGBTQ Catholics would go beyond papal statements unmet by institutional implementation.

The report correctly observes that people who are “marginalized or excluded” on the basis of their “identity or sexuality” would like to be “heard and accompanied” (16). Yet it leaves out of sight the many LGBTQ people who are already bringing their gifts to the church (including the Synod).

The report stipulates that “listening is a prerequisite for walking together in God’s will,” but fails to require venues for listening, or to give signs that LGBTQ voices are being taken seriously at the level of ecclesial practice. Indeed, the Synod report did not even use the term “LGBTQ.”

For many LGBTQ Catholics and their allies, it was hard to avoid the conclusion that Synod-wide commitment on this issue was grievously lacking. Many experienced frustration if not outrage; grief if not hopelessness.

The lament of Psalm 13 rang true for many: “How long, O Lord? Will you forget me forever? How long will you hide your face from me? How long must I wrestle with my thoughts and every day have sorrow in my heart?” Some who had wondered whether other Christian communions might offer them a more grace-filled home were one step closer to the exit door.

It seems clear that debates on LGBTQ topics involving Synod participants were lively, even confrontational.

Yet, according to some reports from inside the Synod, engagement on LGBTQ topics was much more central and intense than it may seem from the spare and indirect wording of the final report. Speeches expressing “skepticism toward efforts to better integrate LGBTQ Catholics into the church’s ministries” were given by delegates of diverse origin, including participants from Eastern Europe, Africa and Australia.

These declarations were passionately “countered” by “personal testimonials calling on the church to urgently reexamine its approach to LGBTQ persons, greeted by rounds of applause.” It seems clear that debates on LGBTQ topics involving Synod participants were lively, even confrontational.

This raises the difficult question of how to proceed to a resolution (or at least compromise) that could satisfy Catholics from many Catholic cultures and subcultures—with very different viewpoints and a history of friction.

At least until recently, Pope Francis has proceeded with LGBTQ inclusion through symbolic actions and gestures of support, moves and countermoves—but not through edicts. After all, the pope is responsible for the whole church, and he needs to bring diverse “Catholicisms” along in a mutual conversionary process. Sex-gender dictates from “the top” are demonstrably ineffective in transforming local churches and their cultures, evidenced by the widespread disregard among German bishops for both “Humanae Vitae” and Vatican prohibitions on blessing same-sex unions.

Perhaps Pope Francis intended the two-part Synod, like the Synod on the Family, to embody a serious, dialogical process of ecclesial trust-building, conversion and reform.

Arguably, heavy-handed papal interventions won’t work and are even likely to harden resistance. Perhaps Pope Francis intended the two-part Synod, like the Synod on the Family, to embody a serious, dialogical process of ecclesial trust-building, conversion and reform.

Insight on this possibility may come from portions of the Synod report that were not on LGBTQ topics specifically, nor even on gender, sex and marriage. Particularly notable are the calls for “theological reflection” that appear throughout. In context, theological reflection seems to connote new or reinterpreted theological ideas—ideas that have developed in a careful process of listening to those with different experiences.

Reflection is always accompanied by practices of inclusion and friendship, practices that cultivate, in pragmatic and interpersonal ways, empathetic openness to another’s experiences. Listening results not only in changed ideas, but in changed realities and relationships going forward. “A synodal Church needs to be a listening Church, and this commitment needs to be translated into practice” at multiple levels of pastoral practice, reads the report (16).

To discern the work of the Spirit requires “a life lived in authentic discipleship,” the Eucharist and community-building “in light of different ecclesial experiences” and informed by the human sciences (1). Sometimes the Spirit “speaks beyond the borders of the ecclesial community,” beginning in us “a journey of change and conversion” (Part 16). Moreover, no less than in armed conflict, “courageous processes of reconciliation” will signify that “we can manage conflicts raised in a nonviolent way” (5).

Listening results not only in changed ideas, but in changed realities and relationships going forward.

Keeping in mind that conversion is a “journey,” it is important not to miss or diminish post-synodal signs that came from the Vatican prior to the publication of “Fiducia Supplicans.” Two follow-up statements issued in the first weeks after the Synod seem to provide a bridge to the document on blessing couples in same-sex unions.

The first, an apostolic letter on the sources and methods of theology, advised that Catholic theology needs to adopt a more contextually responsive approach and incorporate interdisciplinary knowledge about the human reality into its normative vision. In the cases of sexual orientation and gender identity, interdisciplinary insights are abundant and readily available.

The second statement is from the Vatican’s Dicastery for the Doctrine of the Faith (D.D.F.), confirming that transgender people can be baptized, witness marriages and serve as godparents. On the one hand, many will wonder incredulously why something so basic as LGBTQ eligibility for Christian baptism is even an issue. On the other hand, the timing of this affirmative gesture toward trans Catholics—answering an episcopal query from last July—seems significant.

Whereas Synod hospitality to gay people failed to get off the ground in any meaningful way, this move by the Dicastery specifically adds trans people to the Catholic “communion of saints.” And the response was signed by Pope Francis, despite his notorious allergy to “gender ideology.”

“Fiducia Supplicans” and its reception

In December, the D.D.F. issued “Fiducia Supplicans,” signed by Pope Francis. Surprising many and shocking some, the declaration permits the pastoral blessing of same-sex couples and others in “irregular situations” (31), provided that no formal liturgical rite is used and the occasion in no way resembles a wedding (39).

The declaration stresses that pastoral blessings are conferred in many instances where the faithful seek consolation, hope or encouragement.

The declaration stresses that pastoral blessings are conferred in many instances where the faithful seek consolation, hope or encouragement, without an inquiry into all the relations and practices in which the recipients are engaged (21, 29, 32-34). The case is not different here: Only persons are being blessed, not their unions. After all, we are all “sinners” (32).

Pastoral prudence and discernment should guide whether, when and how to confer the “blessings of same-sex couples” (41), but, as a later clarification states, pastors are not at liberty to “support a doctrine different from that of the Declaration signed by the Pope” (3).

This intervention has been met with mixed responses. In regions where there is cultural acceptance of LGBTQ people, their committed unions and even civil marriage—including in the United States and western Europe—the permission has been hailed by many (not all) Catholics as a breakthrough for a Gospel-based welcome to people often stigmatized in the name of religion.

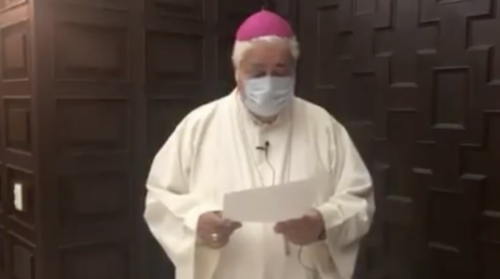

However, in most African countries and some regions in eastern Europe—for example, Hungary and Poland—the permission has been protested as culturally offensive and at odds with Catholic theology on marriage. Catholic bishops in Malawi and Zambia quickly announced that they will instruct their clergy against blessing same-sex couples.

Positively, “Fiducia Supplicans” may yet work as a pastoral solution by allowing Catholics and Catholic leadership in different contexts to affirm the document selectively.

A January “clarification” by the D.D.F. attempted both to allay concerns and discourage either supporters or detractors from seeing the declaration as church support for same-sex marriage. The clarification emphasizes that the declaration does not amount to a change in marriage doctrine and does not include same-sex unions within marriage. Same-sex unions are not being approved as such, but only the individuals in them, and only insofar as they are petitioners before God.

This may be confusing or perceived as disingenuous. After all, “couples” to be blessed have been singled out for notice specifically in terms of their relationships (i.e., same-sex unions and “irregular” situations). Is this document really adding nothing new to LGBTQ acceptance, beyond what was already permitted, and in fact, occurring? Should LGBTQ people then take no encouragement from it? If not, then what was its purpose?

There is a danger that neither opponents nor advocates of the blessings will be satisfied by seeming unclarity about whether the Catholic Church is or is not offering a new level of welcome to couples in same-sex unions.

Positively, “Fiducia Supplicans” may yet work as a pastoral solution by allowing Catholics and Catholic leadership in different contexts to affirm the document selectively. They will encourage or set conditions on blessings, according to what seems demanded by their contexts, without taking measures that are either innovative or resistant regarding magisterial teaching.

To the extent that blessing same-sex couples becomes part of a local Catholic culture, occasions for listening to their experiences will multiply.

To the extent that blessing same-sex couples becomes part of a local Catholic culture, occasions for listening to their experiences will multiply; the immediacy and authority of their narratives will expand within the church, along with more creative theological reflection. Shared practices, listening and creative theology are interdependent. Theology won’t become more creative in isolation from the fellow Catholics upon whose ecclesial status it reflects.

We “Westerners” must respect other cultures and be willing to receive criticisms and caveats regarding our own deeply held convictions and practices surrounding gender roles and sexual norms, as on other matters. We must respect those who sincerely believe that church teaching forces them to oppose many advances for LGBTQ people that we, in the West, may take for granted. We should engage with them constructively and in friendship whenever possible.

We “Westerners” must respect other cultures and be willing to receive criticisms and caveats regarding our own deeply held convictions.

Yet can basic human dignity be open to dispute? In some countries, LGBTQ status merits imprisonment or the death penalty; more widely, including in North America, LGBTQ people are targeted for abuse and violence. Debates about “Catholic” affirmation of their unions might be a “stand in” (but obfuscation) for larger debates about the value, rights and civil law protections for LGBTQ people.

Since any and all violence against LGBTQ people is clearly against Catholic teaching, the upcoming Synod session this October seems an opportune occasion to affirm their place in church and society, and to protest every practice and policy that results in abuse and death.