People around the world commemorate International Holocaust Remembrance Day on January 27, the anniversary of the Allied liberation of the Auschwitz-Birkenau concentration camp in 1945.

In Israel, all activity stops at 10:00 a.m., when wailing sirens signal two minutes of silence. At the United Nations, ceremonies, lectures and public exhibitions play out over several weeks. Even the Vatican marks the day in various ways.

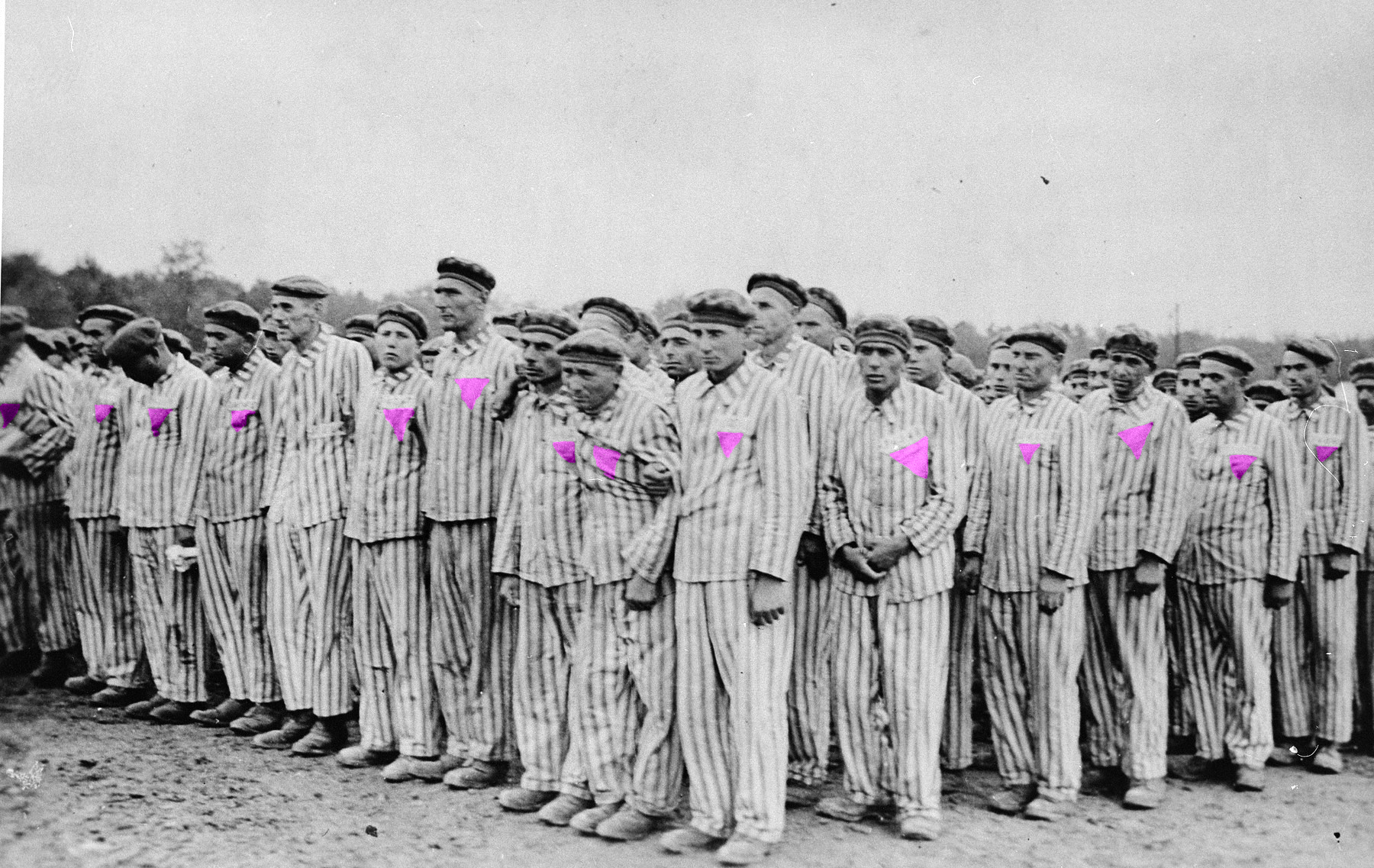

Although first declared by former German president Roman Herzog to remember the millions of Jewish people systematically killed by the Nazi regime, Holocaust Remembrance Day now also memorializes Roma, Jehovah’s Witnesses, political dissidents, people with disabilities and gay people put to death by the Third Reich. As a Catholic gay man, I take a moment on this day to say a prayer for my queer siblings who perished, recognizing that it could have easily been me in their shoes.

As a Catholic gay man, I take a moment on this day to say a prayer for my queer siblings who perished, recognizing that it could have easily been me in their shoes.

The Holocaust and its aftermath were a wakeup call for the world to grapple with the hateful ideologies, histories and cultures that gave rise to the terrors of Nazism. Roman Catholics wrestled with their own culpability. How had Catholic theology, spirituality and practice contributed to widespread anti-Semitism? Why didn’t more Catholics confront the horrors of fascism?

The answers to these questions became more clear as the 20th century unfolded. Catholic thinkers such as Johann Baptist Metz, who, drafted as a teenager by the Wehrmacht, became a Catholic priest and political theologian after the war; Jacques Maritain, a French philosopher who challenged anti-Semitism before, during and after the conflict, offered new paradigms for thinking about Judaism and religious violence.

During the papacy of John XXIII, the church removed the Latin word perfidis (in English, “perfidious”) from the Good Friday Prayer for the Jews. Actions such as these laid the groundwork for the Second Vatican Council, which completely reimagined Catholicism’s relationship to Judaism in documents like “Nostra Aetate,” the Council’s declaration on the relation of the church to non-Christian religions.

Since Vatican II, theologian Massimo Faggioli writes, the Holocaust has become “much more visible and part of the life of the Church” and “an integral part of Christian theological reflection.” This was especially evident during the pontificate of John Paul II, who, exposed to the horrors of World War II in his younger years, took a special interest in improving relationships with Jewish communities.

While Catholic leaders spent the latter part of the 20th century building healthier ties with Judaism…they invented new ways of dehumanizing gays and lesbians.

For good reason, the vast majority of the church’s reflection on the Holocaust has been dedicated to dialogue with Jewish communities and rooting out Catholic anti-Semitism. But this does not absolve the Catholic Church of contributing to a culture before, during and after the war that also dehumanized homosexuals. In fact, while Catholic leaders spent the latter part of the 20th century building healthier ties with Judaism and reminding believers that Jesus was Jewish, they invented new ways of dehumanizing gays and lesbians and excluding them from their own church.

In 1975, for example, two years after the American Psychiatric Association de-pathologized homosexuality, the Vatican first used the term “intrinsically disordered” to describe same-sex desire. Sixteen years later, the Congregation (now Dicastery) for the Doctrine of the Faith, the Vatican’s doctrine office, compared homosexuality to mental illness and claimed that governments had the right to limit civil liberties for homosexuals, who posed a threat to society.

In 2005, the former Congregation for Catholic Education prohibited men “who [had] deep-seated homosexual tendencies” from entering seminaries because, it argued, they “find themselves in a situation that gravely hinders them from relating correctly to men and women.’”

Why hasn’t the Holocaust forced the Catholic Church to confront its homophobia in the same way that it confronted its anti-Semitism?

According to most historical accounts, an estimated 5,000 to 15,000 homosexuals suffered and died in Nazi concentration camps. (And some 90,000 were arrested within a two-year period.) Survivors of the camps recounted horror after horror: forced labor, beatings, starvation, castration, medical experimentation and psychological and sexual abuse from guards and inmates alike. Suicide was common.

Why hasn’t the Holocaust forced the Catholic Church to confront its homophobia in the same way it confronted its anti-Semitism?

In his 1972 book The Men with the Pink Triangle: The True Life-and-Death Story of Homosexuals in the Nazi Death Camps, Joseph Kohout (using the pen name Heinz Heger) recounted, “Jews, homosexuals, and [Roma], the yellow, pink and brown triangles, were the prisoners who suffered most frequently and most severely from the tortures and blows of the SS and the Capos. They were described as the scum of humanity, who had no right to live on German soil and should be exterminated… but the lowest of the low in this ‘scum’ were we, the men with the pink triangle.”

To compound the suffering of queer victims, after the war, Western society quickly forgot about those who had been imprisoned for homosexuality. Under Paragraph 175 of the German criminal code, homophobia remained the law of the land long after the Nazi era, forcing many homosexuals into continued hiding. Between 1949 and 1969, more than 100,000 men in West Germany were arrested for homosexuality and some 59,000 were convicted of breaking the law. Although enforcement of Paragraph 175 became lax after 1969, it was not fully revoked until 1994, several years after German reunification.

Because homosexuality was still criminalized after the concentration camps closed, gay survivors were loath to share their experiences with the world. A public reckoning with the Nazi persecution of homosexuals began around the publication of Kohout’s account, decades after the war. It took years for Germans to take notice.

Between 1949 and 1969, more than 100,000 men in West Germany were arrested for homosexuality, and some 59,000 were convicted of breaking the law.

Richard von Weizsäcker, the former president of Germany, acknowledged Nazi atrocities against homosexuals in 1985, four decades after the war’s end. In 2002, the German Bundestag finally pardoned those who had been convicted under Paragraph 175. By then, most of those affected had already died.

It has taken the Catholic Church much longer to acknowledge its own role in perpetuating deadly homophobia, but there are signs of hope. In 2023, the German Bishops’ Conference issued a statement that acknowledged the ways “homosexuals and other people with queer identities were humiliated, betrayed and murdered” during the Holocaust, along with a stark admission of the church’s support for “homophobic behavior during National Socialism and afterward.”

According to Auxiliary Bishop Ludger Schepers of Essen, who delivered the remarks, the Synodal Way has led church leaders to a growing recognition “that people are fully God’s creation, regardless of their sexual orientation and gender identity.” For that reason, it is incumbent on Catholics to confront prejudice against LGBTQ people and “establish an inclusive climate within the church so that we are a safe place for queer people too.”

The German Bishops’ Conference has taken a bold stand to acknowledge Catholic complicity in the suffering of homosexuals under Hitler’s regime.

The German Bishops’ Conference has taken a bold stand to acknowledge Catholic complicity in the suffering of homosexuals under Hitler’s regime, but it is only a first step for the worldwide church. While the Holocaust rightly forced Catholic leaders to radically reimagine the tradition’s relationship to Judaism, pervasive homophobia has prevented the Vatican from doing the same in its relationship to the queer community.

Today, most of Western society has turned away from the great evil of homophobia, and it is long past time for the institutional church to do the same. As Catholics commemorate International Holocaust Remembrance Day, may we commit ourselves to rooting out persecution and oppression wherever we find it until, with all people of good will, we can rise up and honestly say, “Never again.”