We are not doomed because we are homosexual, we are only doomed if we live in despair because of it.

Andrew Holleran

Half a century ago, a young scholar set out on an uncommonly romantic quest: to find the long-lost door between Christianity and the homosexual experience. Both obedient son and radical of the most fundamental sort, the historian John Eastburn Boswell lived, worked and worshipped in the unshakeable conviction that what appears to hold the two at odds is, in fact, nothing but an illusion.

A self-described “maker of swords” to battle ignorance and oppression, Boswell, born in 1947, witnessed the opening salvos of the same battles that continue to rage in our own time. In response, his academic work became witness to the core message of his personal faith, a message our world still stands most in need of hearing: love is the one infinitely translatable tongue. John Boswell was a seeker of truth, a forerunner in the field of LGBTQ studies, a devout Catholic, an object of the most extraordinary plaudits and the lowest slurs from both right and left and near hero-worship from his friends.

A self-described “maker of swords” to battle ignorance and oppression, Boswell witnessed the opening salvos of the same battles that continue to rage in our own time.

At the apex of his career as Yale University’s first openly gay professor, Mennonites and medievalists, Capuchins and sexologists all clamored for a speaking engagement. Such was the breathtaking range of Boswell’s expertise and the depth of its relevance to modern social crises. He was a man whose facility in foreign tongues made them foreign no longer, a man with a knack for tracing the bright unitive ribbons of human experience to their common origin, though they unspooled along unique paths.

Few modern historical works have had a greater impact on contemporary society than Boswell’s seminal text, Christianity, Homosexuality, and Social Tolerance, wherein he made a compelling case that it was perfectly possible to be queer and Christian. In fact, people had been doing it joyfully for centuries. His assertion was nothing short of revolutionary: that homosexuality and Christianity had lived in fruitful symbiosis from the church’s earliest days through the 13th century, when unprecedented socio-cultural change across Europe replaced this harmony with hostility.

Moreover, this shift occurred when other minority populations were experiencing a similar intensification of prejudice and persecution for many of the same reasons. It was hostility bred of historical accidents rather than theological essence which accounted for the modern institutionalized divide between homosexuality and Christianity. It was Boswell, building on the early efforts of Anglican scholar Derrick Sherwin Bailey, who first comprehensively and systematically demolished homophobic interpretations of the so-called “clobber verses” in Scripture. All later developments in this field are dependent upon his foundation.

Who was John Boswell? What was it that enabled him to see what no one else saw? How do his discoveries bear up over time, and why is their message more crucial than ever?

It was Boswell who first comprehensively and systematically demolished homophobic interpretations of the so-called “clobber verses.”

The perspectives that inform Boswell’s most significant discoveries also form the heart of his own story. “At 15,” he wrote, “I fell in love twice: with God and a boy.” The rest of Boswell’s life—as scholar, lover and person of faith— would be driven by his efforts to reconcile these two loves. Here was a man who accepted the challenge of his father to live within “acceptable moral grounds” by expanding those bounds to include homosexual love. Where his father saw his son’s homosexuality as an obstacle on the road to virtue and honor, Boswell asserted that this essential component of his being was rather the vehicle on that road.

As an adolescent convert to Catholicism, Boswell embraced a vision of the faith which was universal and incarnational to the core. The fruits of such a vision would be amply reflected in Boswell’s scholarship. However, it is through his correspondence, his unpublished creative writing and his many journals that we learn how his faith evolved from a naïve fervor through anger at illogical and unjust strictures, to a renewed confidence based on first-hand knowledge of the sources. These private writings also show just how dearly bought was Boswell’s wisdom, how spectacular professional success was troubled by life-long battles with loneliness, insecurity, depression and doubt. Here, too, is another of Boswell’s many paradoxes.

“Christ’s kingdom, where we all are loved by all on the basis of our souls and human dignity utterly regardless of our skins or pedigrees or genital functions is moving closer,” he wrote with characteristic optimism in 1970. It is for those Christians “with clear sight, who do not confuse what has been with what is right, parental precepts with Christian principles, social prejudice with God’s law, ‘literalness’ with the truth… to promote the radical revolution” that Christ promised. Those committed to realizing the reign of God can expect resistance, but he assures us that “goodness will triumph.” How else could the story of Christianity end?

Combating resistance to a conscience-driven path had been part of Boswell’s religious experience since his youth. Boswell liked to point out that he didn’t stay as a “cultural” Catholic, for his conversion had been a counter-cultural act against the will of his parents and the approval of his friends. “I’ve thought more about this,” he asserted, “than any other commitment in my life.” He would stay, as he remarked in typically piquant fashion, because when “the barque of Peter is in stormy seas, it is better to stay on board and be seasick than to jump overboard and drown.”

The church also represented the institutional face of his own belief in the centrality of love. It was this belief, in turn, which spurred his quest for the seamless garment with which to clothe his existence, so that between eros and the divine there remained not a single uncovered place. It’s a tall order, one might almost say a foolish one. Yet it was precisely this search—restless, passionate, fueled by both brilliance and empathy—that made him beloved by queer people longing for similar raiment for their lives.

What began as an intensely personal quest became for thousands of others a beatitude, a work of mercy of the most fundamental sort. That the impetus and chief goal of his search was a desire to heal his own wounds diminishes nothing of its effect on others. Fortified by impeccable research and based in historical precedent, Boswell offered his own vision of community based on the principle of welcome rather than exclusivity, and unriven by the most deleterious of all schisms: the opposition of body and soul.

It was a vision that inspired many religious and secular LGBTQ people, who came of age in the 1970s and ’80s, and whose experience was one of breathtaking promise and existential crisis. Their voices emerge among the avalanche of correspondence from the summer of 1981, the year after Christianity, Social Tolerance, and Homosexuality hit the shelves.

Boswell offered his own vision of community based on the principle of welcome rather than exclusivity.

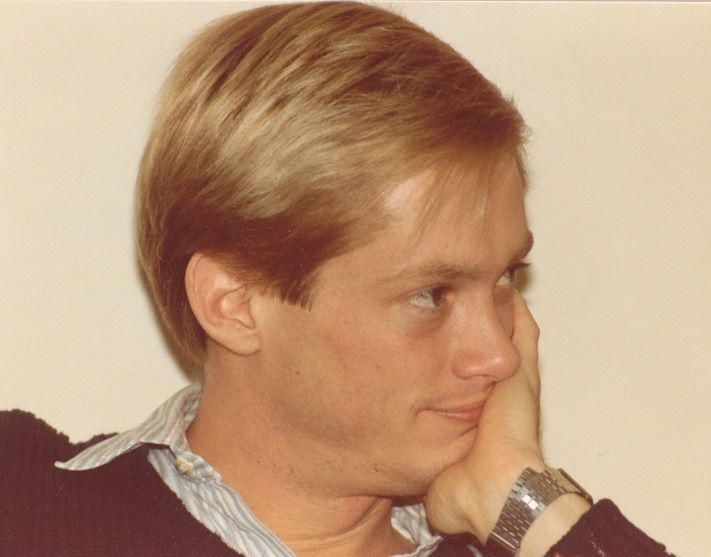

There are hundreds of letters telling him that he should prepare to be lionized and asking him for locks of his hair. There are letters admiring the guts it takes to appear with three shirt-buttons open in the author portrait of an academic tome—and invitations to winter in Palm Beach complete with unlisted phone numbers. There are questions from pert, with-it old ladies who want to know if he himself is gay so that they can win a bet with their friends. There are reassurances, if any were needed, that he is doing God’s work, that he is doing the devil’s work, that he is admired, needed, lusted-after and loved.

“How I wish I was born in the Ancient World [sic] where my lifestyle would’ve been tolerated,” the Pennsylvania farm boy writes wistfully, contrasting what Boswell had revealed about the past with the fear and isolation of his own present. “When I go for a gay experience, I have to go to a big city. I hate anonymous encounters, but what can I do? I can’t let my parents know and I don’t want my neighbors to know either. …I have contemplated suicide and have tried to do myself in twice.”

One senses the exigency of Boswell’s mission in the quiet desperation of this reader. One imagines that he saw himself in many of these letters, as he did in the passion of Sergius and Bacchus, the grief of David for Jonathan or the beloved disciple’s tenderness for his Lord. These were all examples he drew upon to illustrate the continuity and validity of queer experience in the Judeo-Christian tradition. Voices of our past cannot save us, but are we richer (and stronger) for having heard them? Was a farm boy better off for having read of the love of men on his lonely train rides to the city, in the search for love of his own? I believe so.

He aspired to both greatness and belonging in a land dedicated to the myth that one can have both.

Even as debates raged in academic and theological circles regarding Boswell’s interpretation of the past, letters bear witness to the confidence of his queer readership in the necessity of his work. Boswell’s need to understand himself and his place in the world was mirrored by the needs of countless others who had found this yet-unwritten page of queer history an impediment to navigation of life in the present.

His personal journey reflected theirs, and his work took on a special resonance in the last decades of the 20th century, when H.I.V./AIDS ravaged millions and ultimately took Boswell’s life in 1994. Correspondents hoped for a future inspired by the past where homosexual love was not only possible but admired, where homosexual people were fully and openly integrated into the societal and religious landscape.

Boswell wanted to know himself. He wanted to live in freedom. He wanted to heal the broken places and to feel that his being in the universe was neither an anomaly nor a curse. He aspired to both greatness and belonging in a land dedicated to the myth that one can have both. He knew that in a faith haunted by love, there was a place for one of love’s most devoted, if imperfect, disciples. People find themselves amid these hopes and visions, amid the places he’s woven them into words. I know I’ve seen myself there.