In January, I was surprised to see that the German theologian Stephan Goertz published here at Outreach the essay, “How Saint Sebastian became an LGBTQ icon.” The essay came out four months before Herder published his remarkable new book, Sebastian, Märtyrer, Pestheileger, queere Ikone (Sebastian: Martyr, Plague-Healer, Queer Icon). Outreach was the first to publish Goertz on the topic, a clear sign that Outreach is as connected as Goertz is.

Along with his co-author, Stephanie Höllinger, Goertz makes the connections between the Roman soldier martyred for his faith who becomes later protector of those threatened by plagues and eventually an icon for the queer community. Such is the rich complexity of the Catholic tradition.

Having done his doctorate and his habilitation at the University of Münster, with Antonio Autiero as his advisor, Goertz has been the dean of the Catholic Theological Faculty at the Johannes Gutenberg-Universität Mainz since 2018. With his prolific publications and uncanny ability to provoke recognition of the development of Catholic theological teachings, Goertz is very much one of the major contemporary theologians whom people of hope should follow.

Goertz believes that, as a theologian, he needs to help Catholics see how the church struggles to heed the Gospel of Christ.

I first came to follow him as he wrote on Pope Francis’ “Amoris Laetitia.” In light of “Amoris Laetitia,” theologians like Craig Ford, Jos Moons and Francis X. Clooney, S.J., have noted here at Outreach that the apostolic letter of Pope Francis invites us to reconsider what constitutes the church’s pastoral understanding and theological stance of accompanying those looking to partner and marry.

When “Amoris” was promulgated, Goertz edited with his colleague Caroline Witting a compelling collection of essays by theologians entitled: “Amoris Laetitia: A Turning point for Moral Theology?” Calling “Amoris” “a turning point” was a brilliant move by Goertz. He recognized from the outset that definitely something new was happening in magisterial teaching, a more merciful, hospitable teaching was emerging—one much more interested in accompaniment than in anything else.

The remarkable volume was published in Germany and in Italy. He concluded the Italian volume with an essay that he co-authored with Antonio Autiero, reviewing Pope Francis’s own way of teaching in “Amoris,” of what he emphasizes as well as what he omits, as well as how other members of the hierarchy note critically those omissions.[i] Autiero and Goertz wanted us to see just how much a turning point “Amoris” was, though at the same time, highlighting an ambiguity in what remained to be done so that that accompaniment had a veritably stable, institutional foundation.

Goertz believes that, as a theologian, he needs to help Catholics see how the church struggles to heed the Gospel of Christ, to understand the signs of the times and to listen to what faith and reason disclose. He understands well that medieval insight to stand still on the way of the Lord is to move backwards.

Still, he is not one to reduce matters to a sound bite, but rather insists on catching the complexity of matters.

For example, in 2019, in a volume on love, sexuality and partnering, he contributed an essay asking whether we were on the way as a church to accepting homosexuality, noting the developments but also the unresolved issues in the assessment of homosexuality.[ii]

He is not a simple bystander. On the contrary, he is a theological leader who brings his colleagues together so as to respond to the challenges in our church and our world.

For instance, most of us can remember hearing about the words of Pope Francis who, while returning from a World Youth Day celebration in Brazil, was asked by a journalist about gay priests and replied “If someone is gay and he searches for the Lord and has good will, who am I to judge?”

[Goertz] is not a simple bystander. On the contrary, he is a theological leader who brings his colleagues together so as to respond to the challenges in our church and our world.

This was a critical moment that Goertz would again recognize. In 2015, he published “Wer bin ich, ihn zu verturteilen?” Homosexualität und katholische Kirche. It is hard to underestimate the impact this book has had on the Catholic Church in Germany. Goertz began the volume with these words:

In the liberal societies of the West, the idea of the universality of certain inalienable human rights has led to a historically unique process of emancipating sexual minorities and democratizing a variety of relationship structures. Globally, we see the ongoing decriminalization and depathologization of homosexuality, which began after World War II.

Then, he adds, “In the teaching and practice of the Catholic Church, however, same-sex sexuality remains grounds for exclusion.”

The ever-exact Goertz recognized an ambiguous problem with the papal utterance: the Catechism continues to condemn homosexual behavior. Goertz asks, “Should the homosexual person be protected from moral disgrace, (“Who am I to judge him?”), while their sexuality and relationships are not?”

So as “to establish a theological consensus on principles that could lead us to an ethically justified position,” Goertz invited a dozen major scholars into the project to examine biblical claims, to investigate the research found in human and social sciences, to enter into the theological and ethical debates, and to learn from the sociological findings on same-sex partnering and parenting.

(In 2022, the book came out in English, “Who Am I to Judge?”: Homosexuality and the Catholic Church.)

Goertz’s agenda is not a matter of willful opposition to the church’s teaching. Rather, he takes the teachings seriously but looks to see whether new matters from biblical studies, scientific research, sociological investigations and a further understanding of pastoral care ought to prompt us to recognize whether some of the church’s claims are still credible.

As John T. Noonan, Jr., taught, the church continues to develop its teachings: what it once permitted on slavery and capital punishment, it today resolutely opposes; what it once banned on money-lending, it now to some extent permits. Its teachings on just war continue to evolve and take shape. The list goes on. It is, after all, a living tradition.

Today, Goertz recognizes ethically-justified arguments for same-sex relationships. He connects scholars and their research together to help us to see how we could go forward together with these arguments. Indeed, in a recent significant essay, Michael Lawler and Todd Salzman, who contributed to Goertz’s volume, are involved in a very similar task.

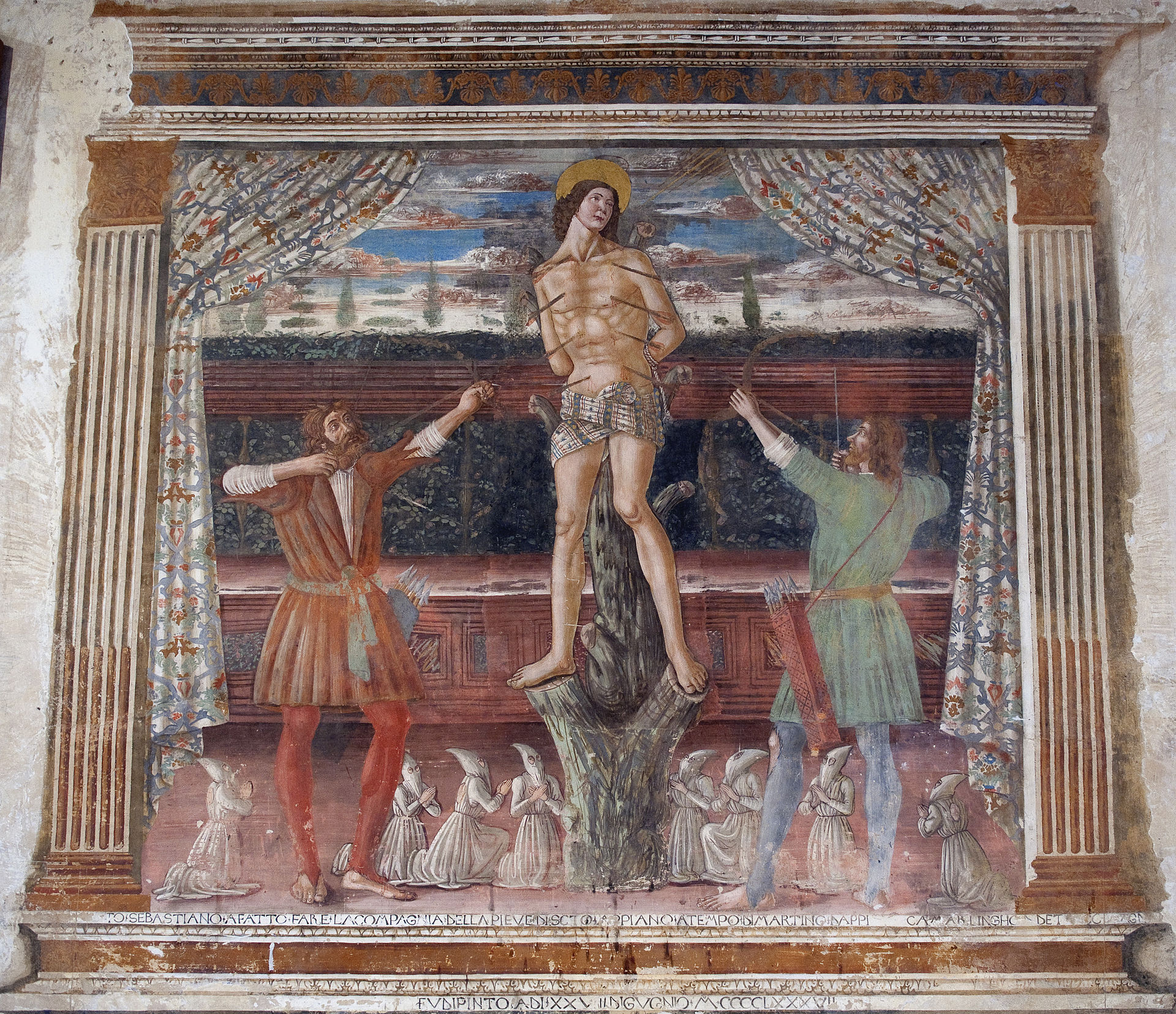

But as he continues his work, let us conclude by returning his new book. Goertz is now promoting Saint Sebastian, by recognizing a soldier martyred for his faith in the early church who becomes known later for plague protection in medieval Europe and as an icon in queer circles in modernity.

Among his many findings, I want to underline three. First, Sebastian was not killed by arrows. Originally caught as a soldier secretly encouraging martyrs to remain steadfast in their faith, Sebastian was sentenced to be executed by arrows under the orders of Diocletian. The resilient Sebastian was nursed by Saint Irene back to health and then publicly confronted the emperor for persecuting Christians.

On the emperor’s orders, he was then bludgeoned to death. Later, he became patron of those at risk to plague when in the seventh century his relics are sent to Pavia under siege by such a plague. The plague abated and Sebastian was recognized as a plague-healer.

Goertz is a theologian who connects others so as to recognize what needs to be seen.

Still, as Goertz noted, Sebastian’s success in Pavia was not known elsewhere until the 14th century work, The Golden Legend, recounted the story. Then, the plague returned throughout Europe and the resilient relics of Sebastian did as well and Sebastian’s role as plague healer was set across the continent.

Finally, recognizing that the soldier martyr could not have been shot with arrows if dressed in armor, Renaissance painters began to convey the near-bare body of Sebastian as beautiful. In time, the queer community found in Sebastian, once a secret Christian who becomes a public advocate, a true companion. When H.I.V./AIDS emerged, they found in this irrepressible plague-healer, a hope-filled icon of accompaniment.

Goertz is a theologian who connects others so as to recognize what needs to be seen. Through his discoveries, he leads us in hope through a church able to grow in the 21st century. May his findings and hope assist us as well.

[i] Antonio Autiero and Stephan Goertz, “A proposito di dubbi, errori, e distinzioni: Una postfazione,” Stephan Goertz/ Caroline Witting (ed.), Amoris laetitia. Un punto di svolta per la teologia morale? Milan: Saon Paol, 2016, 257-270.

[ii] Stephan Goertz, “Auf dem Weg zur Akzeptanz? Katholisch-theologische Entwicklungen und Zwiespalte in der Bewertung von Homosexualität,” in: E. Schockenhoff (Ed.), Liebe, Sexualität und Partnerschaft, Freiburg/München: Herder, 2019, 105-130.