I often wonder out loud with other Catholics, “How do people without faith do it?” In our conversations, we’re not judging others, but are genuinely mystified how anyone walks through the dark hours of life without relying on the clarity of light that we ourselves seek.

My own church, in the heart of a New England city, is a Franciscan beacon that has sustained me through tumultuous life events and led me to joy. It has guided me for over a decade toward the orb of Christ’s love. I never expected this light to grow wider in every direction, but it has, bouncing around my world, pinging and pulsating everywhere.

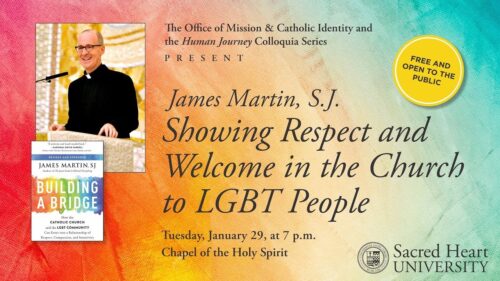

So imagine how my stomach turned when I found out that several Sundays ago, during an afternoon Mass that I did not attend, eight people protested outside our thriving and holy sanctuary. Why? Because it’s a Catholic refuge for the LGBTQ faithful.

I don’t know who these people were. And I’m completely caught off guard by the level of rage in me, and saddened by it. It’s not who I want to be and I hope that forgiveness finds me. But as a straight woman, I’ve never had anyone try and quench my longing for God with their own contempt.

It’s beyond anything I can fathom, someone choosing to spend their Sunday hours sullying the beauty of my church. Did they pray more loudly for our redemption as our Assisi-like bells peeled before Mass, calling all people in?

It’s beyond anything I want to fathom, someone choosing to spend their Sunday hours sullying the beauty of my church.

What struck me deepest is that regardless of the denomination, these disruptors, these fissures, exist in my own faith. The Catholic Church right now is a twisting landscape regarding the issue of LGBTQ rights and inclusivity. To illustrate my stance, I’d like to turn to Visio Divina, the sacred practice of looking at an image, and praying on how it speaks to our hearts.

Vincent Van Gogh’s The Starry Night, one of the most beloved paintings in the Western world, is aflame with emotional luminosity, yet the chapel in the center is the one structure in out-and-out darkness. Lamentably, for many LGBTQ people, this is their experience of Catholicism—a darkened chapel with not a dab of amber, not a single brushstroke of gold-white.

I’ve gotten lost in the warp and waves of this masterpiece as a reproduction (on postcards, socks, scarves) and visited the actual painting, housed in New York’s Museum of Modern Art, once. It was an ecstatic experience for me. But only recently was I actually shown the truth of the church. I never noticed it before.

While listening to the podcast “Renovare,” on the connection between Henri Nouwen and Van Gogh, the guests discussed the theory ofwhy Van Gogh chose to render it without any light, when the entire rest of the night-sky exploded. How had I never registered the cold, empty building before, even though I had crossed paths with this image a thousand times? This new perception left me dumbstruck. What had happened to him?

Upon my first pondering of the unlit church, I thought: This is potentially how it feels for LGBTQ Catholics.

Like most people, I knew that Van Gogh suffered in a multitude of ways. I had also read many of his copious letters to his brother Theo, where he articulated that within his burdens, he carried a continuous faith.

What I didn’t know, until that podcast, was that when he was a young man, before he dove wholly and intimately into his calling as an artist, he spent six ardent months as a Christian preacher in Belgium. After this half-year effort, his appointment was not renewed, because he was perceived as lacking in skill as a preacher.

Van Gogh was devastated. He felt discarded and undervalued. Art historians posit that because of this, he never stepped foot in a church again. This holy, tender soul was turned away. S

So what should have been a nourishing sacred space for Van Gogh became a building made of darkness. He painted The Starry Night, in 1889, in the French asylum where he was sent near the end of his life. The view is partially accurate—we know the exact constellations and lunar cycle that flared outside his window—and partly from the sparks of his memory. The steeple, for example, is one which existed all the way back in the village of his childhood.

Surrounding that spire, the entire world of the painting erupts with an ineffable energy, what for us, as Christians, might be called the Holy Spirit. Upon my first pondering of the unlit church, I thought: This is potentially how it feels for LGBTQ Catholics. But this view is—and I have to turn to this word, though overused—a privileged, straight perspective.

I am a member of a particular arm of the church that is welcoming to gay and lesbian people, but am also part of the larger organization that often is not welcoming. I do not accept that this is who we are meant to be. And I wonder how people without faith live their lives, when there are people with faith who seek entrance through various thresholds of the church, but are not welcomed in their true light.

Until the LGBTQ community is fully welcomed, we are looking out at a tumbling landscape with the windows of our church dark.

I can’t forget, and don’t want to forget, that people are targeted in my church in an attempt to diminish, to dim. And now that I’ve beheld the unlit center in The Starry Night, the entire painting has taken on a new meaning.

I’m not saying I am better because of my own spiritual path. Rather, I am grateful to be part of the lucidity of the Franciscan Way, guided as a disciple to the perfect truth of Christ. “I am the light of the world. Whoever follows me will not walk in darkness, but will have the light of life.” (Jn. 8:12) And “I am the door.” (Jn 10:9)

Yes, the door is wide open to everyone. Leading to a sky of wonder where all of us move like breath over the horizon, together in the holy. But until the LGBTQ community is fully welcomed, we are looking out at a tumbling landscape with the windows of our church dark. And our doors? Shut. They’re double-locked.