Editor’s note: This is the second part of an essay by Michael O’Loughlin, the national correspondent at America magazine. Click here for the first part.

Tim Zaricznyj had never planned to work for a Catholic organization, especially one run by sisters.

True, he had grown up in a Ukrainian Catholic family in upstate New York and graduated from a Jesuit high school and college. As a young man, priests had even encouraged him to consider the seminary. He had admired his religion teachers who urged him to question his faith, to draw the best parts from it but not to take it all in blindly.

But Tim’s worldview was ultimately shaped by other realities, as the son of a refugee and the brother of a sibling with special needs. And, as he began to understand as he came of age, his experiences as a gay man.

In 1990, Tim moved to San Francisco. In his mid-20s, Tim had “absorbed” the homophobia expressed by some religious leaders, he told me, including those who suggested that AIDS was a punishment from God. Tim knew differently, through his work with H.I.V./AIDS organizations in the Bay Area. He had no choice, he felt, but to leave behind the faith of his childhood.

That’s why it was perhaps a bit of a surprise when, three years later, Tim found himself interviewing for a position at an affordable housing complex for people with AIDS—being questioned by two Catholic sisters. He had steeled himself for the interview, deciding that he would be honest with the sisters about his own journey, including his life as a gay man.

“I need confidence from you,” he told the sisters, “that I can bring my whole self to work, that I won’t need to edit who I am.”

The sisters didn’t flinch. In fact, they told Tim that being able to relate to the residents in a way that they never could was a selling point. He took the job.

One of the sisters who interviewed Tim—Sister KC Young, O.P.—was not a Sister of Providence, but her ties to the order ran deep. She had been educated by them before entering the Dominican Sisters of Sinsinawa, Wis. While studying in Seattle to become a hospital chaplain, Sister KC lived with some members of Sisters of Providence, which is how she met Sister Mary.

The two sisters struck up a friendship. A couple of years later, when a position opened at Providence House, Sister Mary asked Sister KC if she would like to work there.

One of the selling points for Sister KC was her paycheck. Not the size of it—it wouldn’t be much. But Sister Mary told Sister KC that the federal grants couldn’t be used for services. So instead, the Sisters of Providence would underwrite Sister KC’s salary. The sisters were insistent that the residents have more than a roof over their heads, that they have access to resources that could help them thrive. And they used their resources to back up those ideals.

“That said a lot about their vision,” Sister KC told me, “about what was valuable and important in that ministry.”

“A family environment”

Building community was important to the staff and volunteers at Providence House. They hosted occasional social events and shared meals in the common spaces. When the sisters received a check for $3,000, an unexpected rebate for buying energy-efficient refrigerators, they turned to the residents to ask how to spend it. The consensus: patio furniture and a new grill so everyone could socialize outside. The furniture arrived in several large boxes, and 10 residents spent an entire day assembling chairs and tables.

“It took all day, with many disputes as to what the directions really meant, and lots of laughter as pieces were taken apart and reassembled,” the sisters remembered.

Activities like that brought the residents together.

“There’s comfortable housing, a family environment,” Dan Parish, who found Providence House through a support group for people with H.I.V., told the Catholic Voice. He said that on his good days, he could get around fine. But on his not so good days, when walking a single block felt insurmountable, he relied on the community at Providence House. “For kindness and comfort, you can’t get anything like this anywhere I’ve been.”

Still, even with the strong community, life at Providence House was often difficult.

“There’s comfortable housing, a family environment,” Dan Parish, who found Providence House through a support group for people with H.I.V., told the Catholic Voice.

“There is a serious drug problem, with all the upheaval and crime that go with it,” reads an early report from the sisters. According to an article from the Oakland Tribune, the neighborhood experienced lots of crime, including murder, armed robbery, muggings and many drug-related disturbances.

There was also the daily reality of illness and the all-too-present specter of death to contend with.

Sister KC had trained to be a hospital chaplain, emotionally challenging work. Sickness and death was never easy. But nothing had prepared her for the intensity of the challenges facing the residents at Providence House. One young man, who normally flowed with effervescent energy, looked so down one day.

“What’s going on?” Sister KC asked.

“I just buried my twenty-fourth friend,” he replied, breaking down into tears.

Sister KC held him. And together, they wept for all that loss.

But even in the midst of all that pain and suffering, there were also moments of new possibilities, instances of healing and hope.

Among that first group of residents to make Providence House their home was John Neilson.

John was only in his early 30s, but he had already endured a lifetime of challenges, including sexual abuse, drug addiction and now an H.I.V. diagnosis. When he moved into Providence House, he hoped for a clean apartment and a bed to sleep in. What he discovered, he told me, was much more than that, including a small community dedicated to helping him and the other residents.

When he moved in, John was battling addiction, perhaps fueled by seeing so many of his neighbors move into Providence House and then die from AIDS-related complications shortly after. But he also took several steps toward recovery and healing. He worked with therapists and took advantage of the massage and acupuncture offered at the house.

He began attending Mass and even became a Catholic, not the most likely path for a member of the LGBTQ community in the 1990s. He even rekindled his love of art, eventually creating a series of provocative paintings, some using his own blood, that called attention to the ongoing H.I.V. crisis, which gained him some press coverage in the Oakland Tribune.

Over the years, John developed a friendship with Tim. They engaged in long conversations, worked together in the community garden. One day, Tim paused and looked directly at John.

“Are you ready to go into treatment?” Tim asked him.

“Yes,” John said. “I’m ready.”

Decades later, John credits the community at Providence House, especially Tim, for helping him find a path toward healing.

“It’s been quite an incredible journey,” he told me. “I don’t think I would have gotten clean quite the same way, and started going to meetings, if I hadn’t been living at Providence House.”

John has been drug-free for more than a decade and today, he works to help others battle addiction. He still lives at Providence House, and he lends support to other residents coping with their own journeys through life with H.I.V.

When I asked John what he wanted others to know about Providence House, about the sisters who started it and the staff who stuck by him, he paused for a moment.

“It’s saved quite a few people’s lives,” he stated matter-of-factly. “And it’s given a lot of people hope.”

“All the tragedy with equal amounts of joy”

Forty-four people living at Providence House died from AIDS-related complications during its first five years of operation, according to notes the sisters kept. Drug abuse, which brought crime into the house, was especially prevalent. Some residents, shunned by friends and family and cast aside by society, harbored anger and resentment.

But there were also moments of joy, especially around the holidays. Pumpkin carving and trick or treating for local kids. Thanksgiving potlucks. Kwanzaa celebrations. And a slew of events to celebrate Christmas.

When I recently asked Tim what made Providence House different from other affordable-housing residences, it didn’t take him long to answer. It was the sisters.

The sisters noted that even by just the second Christmas in which residents were living at the house, traditions had already developed.

“This is how we decorate here.”

“We always have a big brunch on Christmas morning.”

“Staff always make special cookies or candy.”

On New Year’s Eve, residents braced for what Sister Mary described as Oakland’s “strange and frightening New Year’s custom.”

“At the stroke of midnight, along with the usual whistles and horns, firearms are discharged into the sky,” she recalled. “Hundreds of gunshots are heard.”

The next morning, residents gathered in the common room for a New Year’s Day brunch. Other times, the common space was used to host social gatherings. Or to display works from local artists. Or even to host a fashion show—for Barbie and Ken.

One of the residents loved to sew and had an eye for style and fashion. Once a year, he took over a common room for the weekend to stage a fashion show unlike anything most people had ever seen. It was “an unusual event,” as one former staff remember recalled, but all weekend, people would come and go, soaking up the dresses and accessories.

“There was so much sadness, but there was also celebration that was always happening,” Tim recalled. “There was really a beautiful balance, countering all the tragedy with equal amounts of joy.”

362,000 Americans

When I recently asked Tim what made Providence House different from other affordable-housing residences, it didn’t take him long to answer. It was the sisters. Tim sent me some photos from that time, including one of him with his arm around Sister KC. He’s wearing baggy khakis and an orange-checkered, button-down shirt. Sister KC sports a dress with a red, gold and black southwestern pattern, along with a blue sweater. They are both smiling big, standing in front of a small kitchen with a couple of large coffee urns.

Tim would have been in his 30s. He looks so young. But that’s not what gives me pause. Instead, I know that many of the people Tim assisted during his time at Providence House were around the same age. So many lives, cut short.

The presence of the sisters shaped the culture of the house. Sister Mary radiated a can-do attitude. Sister KC’s warmth made her a natural at getting residents to open up. There were opportunities for spiritual nourishment, field trips to San Francisco. But more than that, it was a vow the sisters took to serve people in need, which, as Tim put it years later, imbued in the staff and residents some “healthy skepticism about boundaries.”

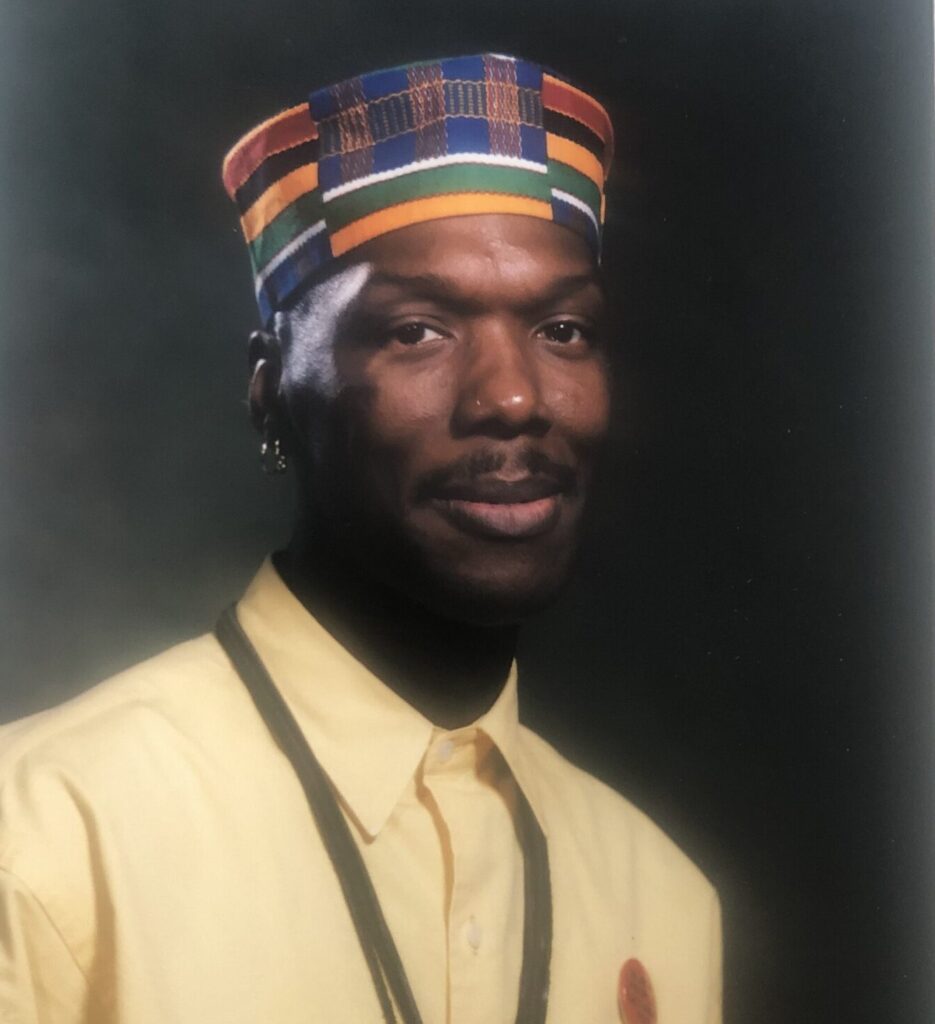

Take Kevin G. Brooks. After graduating high school in New York City in the 1970s, according to a 1996 piece appearing in the San Francisco Examiner, Kevin joined the Navy and eventually moved to Oakland, where he worked as a computer programmer. When his health began to decline in the late 1980s, he left that job and focused his energy on educating others about H.I.V. prevention.

Kevin produced a series about H.I.V. for a local radio station, “The Color of AIDS”; he and a group of friends created an AIDS-education program, rapping about safe-sex in Black gay bars throughout the Bay Area and, eventually, throughout the country. A portrait of Kevin, taken before he became ill, shows a handsome young man, a shy smile across his face.

But by the time Tim met Kevin, in 1995, those days were over.

AIDS had taken a toll on Kevin. He was confined to a wheelchair and was largely unable to care for himself. At first, Kevin treated Tim with skepticism. Tim was white, Kevin was Black. Tim was mobile, Kevin was not. And perhaps most angering to Kevin, Tim was alive. And he was dying.

One afternoon, Kevin was struggling. His caregiver had not shown up. His partner, John, was still at work. He had gotten sick in bed and the extra towels were out of reach. He needed help.

When Tim got a call from Kevin, he heard the fear and anger in his voice. It would not have been inexcusable for Tim to tell Kevin to hang on, that he’d try to find somebody else to clean up. After all, this was not an assisted-living facility.

But Tim thought of the sisters. They responded with compassion whenever there was a need. For the sisters, after all, this was a ministry. Tim had seen that ethos play out many times.

So Tim went up to Kevin’s room. He asked how he could help and they developed a plan. Tim cleaned up the room, remade the bed, got Kevin situated, and then he stayed. He listened.

Over the next six months, Kevin and Tim talked frequently. They learned each other’s stories. Kevin even asked Tim to help spread his ashes in San Francisco Bay when the time came.

In April of 1996, Kevin Brooks died from AIDS-related complications. In his obituary, Kevin asked one final request from those who loved him, to support Providence House. He was just 38, one of the more than 362,000 Americans at that point, mostly gay men, who had died from AIDS.

But for Tim, Kevin was far more than a statistic. He was a friend, one of many in Tim’s life whose stories ended early because of this horrible disease.

A social network

In the first few years that Providence House was open, more than 10 residents died each year. By 1996, with new treatments available, that number was down to four. H.I.V./AIDS was changing, and Providence House had the opportunity to focus on helping residents live. In 2000, their efforts were recognized nationally, with the Department of Housing and Urban Development holding up Providence House for its commitment to providing quality housing to the community.

In the first few years that Providence House was open, more than 10 residents died each year. By 1996, with new treatments available, that number was down to four.

Providence House, which in 2018 was outfitted with new siding, windows and even the installation of solar panels to help with sustainability, still operates today as a ministry sponsored by the Sisters of Providence.

Sister Mary Grondin left Providence House Oakland in 1993, having been assigned to oversee the construction of another affordable housing project. Before she retired, in 2007, she helped launch another AIDS ministry, helping women in Portland, Ore. She died in 2018.

Sister KC Young wrapped up her ministry at Providence House in 1995. She has worked in pastoral ministry in several capacities, including with Native Americans and leading an organization that helps people upon their release from prison.

Tim Zaricznyj, who could never really imagine working for two sisters back in the early 1990s, is now the executive director of Providence Supportive Housing, which operates 17 affordable-housing facilities in California, Oregon and Washington. Nearly 800 people live in units that they otherwise may not be able to afford on their own. Tim says the lessons he learned from the sisters still guide his work.

“We became their family network. We became their social network,” Tim recalls of the residents at Providence House. “I attribute that, not entirely, but significantly, to the presence of the sisters, the sisters fulfilling their obligations and their vows and just doing what sisters do.”