Editor’s note: This is the first part of a two-part essay by Michael O’Loughlin, the national correspondent for America magazine. Click here for part two.

The plans were meticulous, but then reality threw a curveball.

The Sisters of Providence, a Catholic women’s religious order with a large presence in the northwestern United States, hadn’t necessarily sought to provide housing for people with H.I.V./AIDS in the early days of the crisis—the 1980s. But like many other sisters before them, the Sisters of Providence learned of a pressing need in their community and responded with compassion. Then they got to work.

Physicians and support staff at what was then Providence Hospital Oakland, in California, had been distraught each time they discharged a patient with disabilities who had nowhere suitable to go. Perhaps they couldn’t navigate flights of stairs up to their apartments. Or maybe they had nowhere to call home at all, and instead slept in parks and dangerous shelters.

Homelessness was a major crisis in the Eastbay neighborhood in the 1980s, with as many as 9,000 people lacking adequate housing at any given time, the Oakland Tribune reported in 1986.

Was there anything the sisters could do to help?

Having previously opened three facilities offering affordable housing to people living in Washington and Oregon, the sisters said yes. After all, when the founder of their religious order, Emilie Gamelin, ministered in her native Montreal back in the 1840s, she and a small group of other women provided housing to orphans and widows. (Mother Emilie was beatified by Pope St. John Paul II in 2001.) Now, more than a century later, providing access to safe housing for vulnerable people was no less urgent.

By the end of 1985, the sisters had secured initial funding and created plans for a few dozen affordable apartments for low-income adults living with disabilities. After overcoming many obstacles—including a bureaucratic nightmare involving an historic but dilapidated structure situated on their property, popular with people with drug addictions and eventually destroyed by a fire—they broke ground on September 30, 1987.

According to a press release, once constructed, the house would “provide housing for low-income disabled and elderly persons.”

But two years later, construction was still elusive. A powerful earthquake in 1989 damaged city offices, with piles of permits and paperwork a casualty of the tremors. The house would be delayed yet again.

Was this a sign that the project just wasn’t meant to be?

“The people of Oakland need this housing project desperately,” thought Sister Barbara Schamber, S.P., the regional superior of the Sacred Heart Province, recognizing the federal money the sisters had secured would simply vanish if they gave up. “So we will proceed.”

But it would take more than an ironclad commitment to see the house through.

Sister Mary Grondin, S.P., had a passion for social justice

On Ash Wednesday, in 1983, Sister Mary hopped a fence at the Trident nuclear submarine base in Washington State. She walked along the railroad tracks that brought the weapons to the base, stopping occasionally to pray and to place photos of people killed by nuclear weapons. Along with her two companions, Sister Mary was arrested for trespassing, as the Tacoma News-Tribune reported at the time.

“Without basic housing and basic respect, it’s pretty hard to take care of the rest of your life,” Sister Mary told the Catholic Voice.

A few years later, the Sisters of Providence built 60 units of affordable housing at Seattle’s Pike Place Market, which had historically housed many social service agencies. Sister Anita Butler, a member of the province’s leadership team, was tasked with finding a sister to help run the Seattle residences. She thought immediately of Sister Mary. Supportive housing was no easy job. People experiencing drug addiction and mental illness needed fierce advocates. Sister Anita knew Sister Mary was the perfect fit.

When asked about her philosophy of providing housing to people experiencing difficult challenges, the sorts of people society usually likes to keep hidden in the shadows, Sister Mary summed it up succinctly.

“Without basic housing and basic respect, it’s pretty hard to take care of the rest of your life,” Sister Mary told the Catholic Voice. Or put another way, Sister Mary saw in the housing ministry a fulfillment of the commandments to love one another laid out by Jesus in the Gospels.

“This is clearly a participation in the healing ministry of Jesus,” she continued. “Even though this is obviously a building, it’s run on Christian principles and with a respect for peoples’ varying traditions. Walking with people who are disabled or ill, it’s a privilege.”

Back in Oakland, the sisters were trying to get the new residences built, but they needed that extra push. Sister Barbara asked Sister Mary to get on board. After all, as another sister told me, “Sister Mary was relentless, in the best sense of that word.”

Sister Mary arrived in Oakland in late 1989 to devote her efforts to a project that the sister felt was on life-support.

She made it her mission to talk to as many people as possible. She met with hospital administrators. She tracked down local activists. She visited adults living with disabilities.

At this point, plans for the house still called for serving adults with disabilities. That’s what the hospital had asked for. And that’s what the sisters had pledged to deliver.

But “adults with disabilities” was such a broad, abstract category of people, Sister Mary thought. Who were the individuals the sisters would actually serve?

Two groups of people were especially underserved in the Bay Area: adults with mental illness and people living with AIDS. Officials at the Department of Housing and Urban Renewal informed the sisters that the grant money they had received was designated only for physical disabilities, so housing for people with mental illness was off the table.

There weren’t many organizations rushing to care for people with H.I.V./AIDS in Oakland in the 1980s. But then again, there hadn’t been many organizations ministering to poor immigrants with cholera in mid-19th century Montreal. But Mother Emilie Gamelin did. And a century-and-a-half later, following her example, and listening to the pleas from local leaders, the Sisters of Providence took up that call to serve.

In my book, Hidden Mercy, I chronicle stories about Catholics in the United States responding to H.I.V./AIDS with mercy and compassion in the early days of the epidemic. At the institutional level, the response was troubling. Some bishops undermined public health campaigns and others fought against measures that could have made life a bit less terrifying for members of the gay community.

But there are also stories of many other Catholics, drawing inspiration from the teachings of Jesus, who responded with love and compassion, even if their stories weren’t always covered by the press. Priests visiting gay men dying from AIDS who had been abandoned by family and friends. Gay Catholics organizing buddy programs, to make sure their friends and neighbors had meals when they could no longer cook for themselves.

And Catholic sisters, like the Sisters of Providence, who responded with creativity and compassion when confronted with the deep need in their communities. As a gay Catholic myself, learning how others responded with mercy in the face of such stigma and shame has made me more confident in my own faith.

The need for affordable housing for people with AIDS in the 1980s was astronomical. Some people fell behind on rent while hospitalized and faced eviction when they were discharged, the New York Times reported. Others contracted H.I.V. in homeless shelters, which saw disproportionately high rates of the virus. Still others were not welcome back home after their families learned that they had been diagnosed with H.I.V.

By 1990, experts estimated that tens of thousands of Americans living with H.I.V./AIDS lacked access to housing, with one member of the National Commission on AIDS describing that reality as “a national scandal,” according to the Los Angeles Times.

That scandal plagued Oakland, which the sisters noted in their archives was home to just nine units of affordable housing for people with AIDS.

Even for someone with her energy, Sister Mary encountered a formidable opponent in City Hall. Paperwork misfiled in city offices. Small tweaks to blueprints adding delay after delay at the construction site. Special permits were needed. Financing and banking hiccups.

As a gay Catholic myself, learning how others responded with mercy in the face of such stigma and shame has made me more confident in my own faith.

Finally, on September 26, 1990, contractors were given the green light to begin construction, even if Providence House Oakland would take another year before to complete.

Recognizing the vast challenges that the residents would face, the sisters asked Sister Patricia Hauser, a social worker who had previously ministered to people experiencing homelessness in Seattle and Alaska, to assist Sister Mary. With Sister Mary’s nursing background and Sister Pat’s social-work knowhow, the pair of sisters constituted a dream team in terms of holistic care for people living with AIDS.

Six years after the initial idea for what would become Providence House Oakland was first discussed, Sister Mary settled into her apartment on July 31, 1991.

Each resident would live in a private apartment, with a bedroom, kitchen and living room. But many of the future residents lacked furniture, nevermind basics like towels and sheets. So Sister Mary haggled with mattress wholesalers and bargained for the best deals on linens. Sister Pat acquired dressers and nightstands from St. Vincent de Paul and placed announcements in the bulletins of local parishes for more donations.

On August 1st, the sisters welcomed 26 residents, and the day after that, another 14. The residents in the early days of the house reflected the reality of who was being hit hardest by H.I.V./AIDS in the early 1990s. Around Oakland, more than 50 percent of new AIDS diagnoses were among people of color.

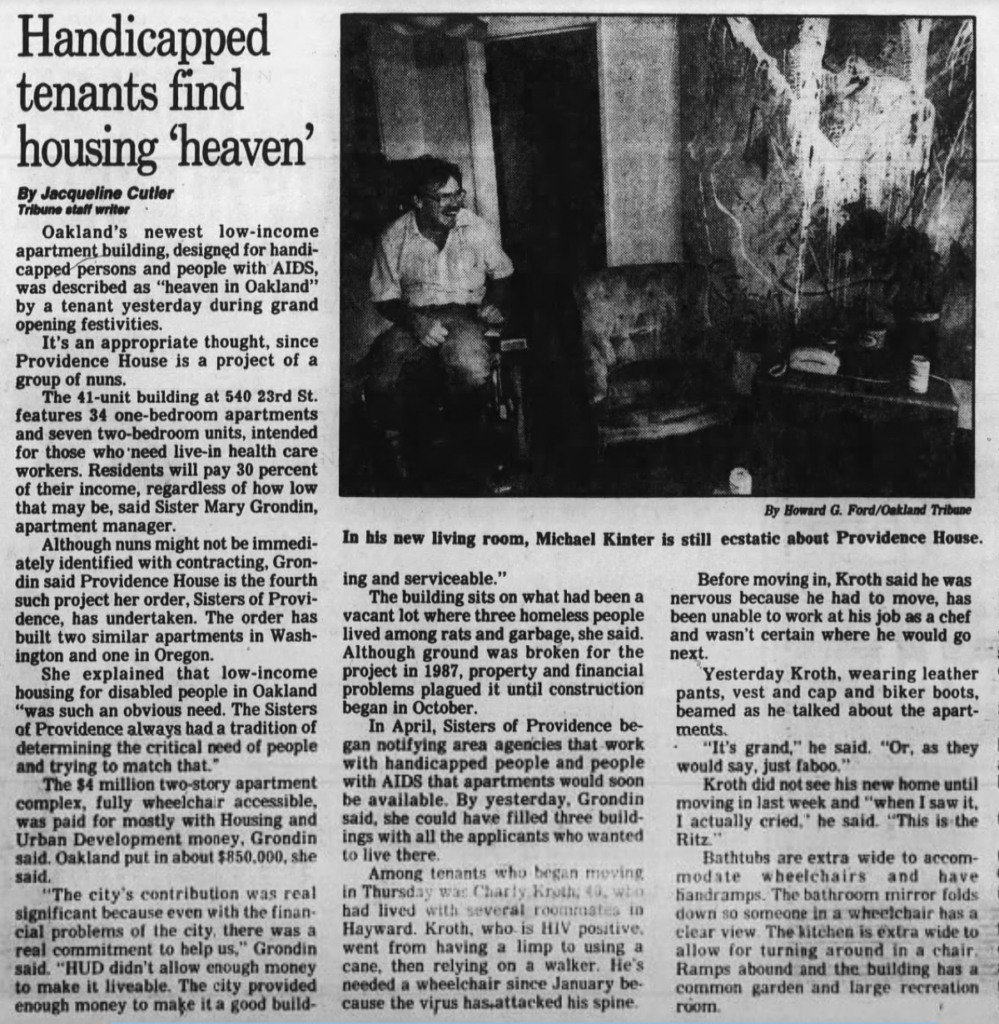

Most of the residents at Providence House Oakland, about 70 percent, were African-American men, and nearly 75 percent of the residents were living with H.I.V. Providence House made just a small dent into Oakland’s need for affordable housing for people with AIDS. There would always be a waiting list. But for those 40 people, the residences were life changing.

Tomorrow, in the second part of this story, a look at how the staff and residents at Providence House worked hard to build a community for people living with HIV and AIDS.