This past July, I was saddened to miss the first Outreach conference in New York City. In true Ignatian fashion, I was discerning between two goods. Even though my desires were pulling me to New York, the Holy Spirit nudged me toward Wyoming instead.

For the past few years, at the Boston College School of Theology and Ministry, I have been studying how queer theology can inform ministry with LGBTQ adolescents and emerging adults. My hopes for the Outreach conference were rooted in this world, but I said “yes” to the Spirit and attended my cousin’s wedding in Laramie.

I have long felt a deep connection to the story of Matthew Shepard and I have spent most of my life relating to Matthew as a queer saint. On October 6, 1998, Matthew—a scrawny, 21-year-old gay student at the University of Wyoming—was picked up at a bar by two men pretending to be gay. They tied Matthew to a fence and beat him into a coma. Matthew died six days later at a hospital in Fort Collins, Colo.

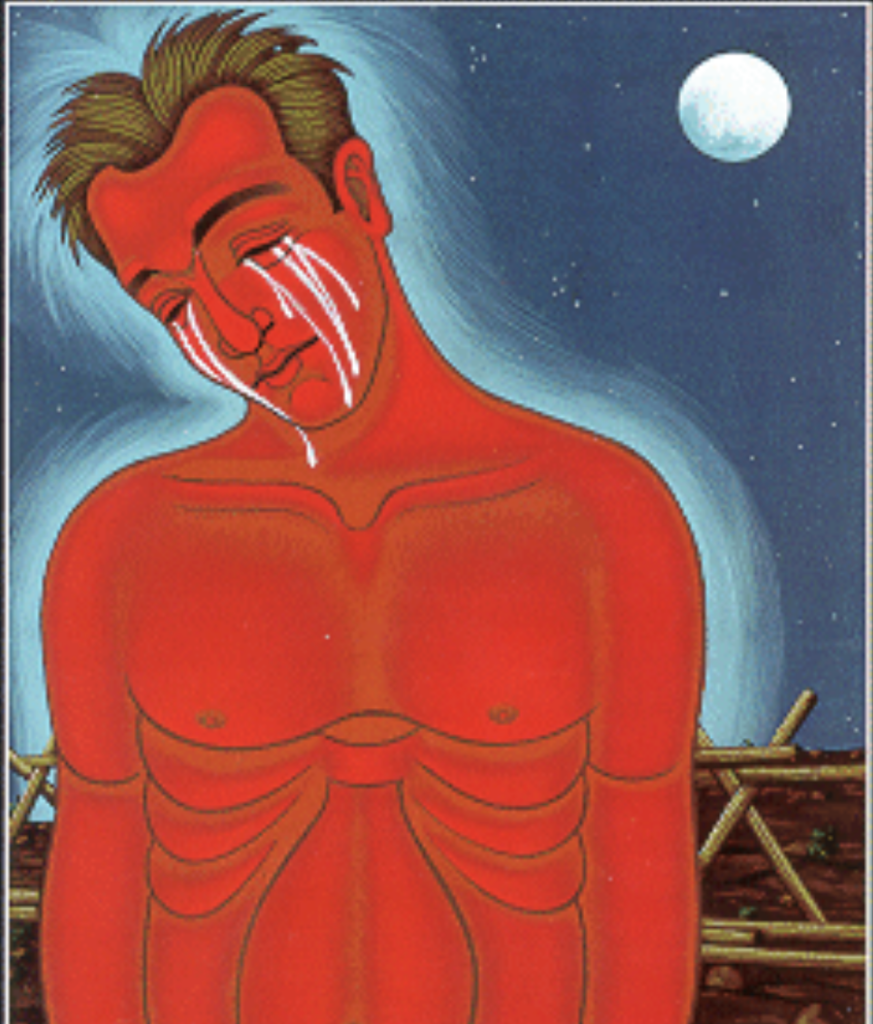

United with God, Matthew is forever a part of the Body of Christ and the Communion of Saints. I imagine Matthew’s queer miracles show up quietly, most likely in the lives of other queer kids searching for belonging and among H.I.V. positive folks. Sometimes I pray to Matthew, and I keep the Rev. William Hart McNichols’ icon (pictured below) near my front door. Every time I head to class, the icon reminds me why I’m studying. Matthew’s story continues to shape me and my “faith that does justice.”

Just like Matthew Shepard’s parents, my parents met as students at the University of Wyoming. Growing up, I reluctantly sported my “Junior Joe” gear at Cowboy football games. As a scared kid beginning to wrestle with understanding my gay identity, I became increasingly anxious in public places that I felt could inflict some kind of spiritual, emotional or physical harm.

Sadly, parts of Wyoming embodied that for me. In October of my freshman year, at a Jesuit high school in Colorado, I heard the news about the brutal attack on Matthew Shepard. According to law-enforcement officials and his parents, Shepard’s sexuality was not tangential to his murder, but the key motivating factor. In the days and months that followed, it was heartbreaking to see Catholic and other Christian leaders openly antagonistic toward Matthew and Laramie’s LGBTQ community.

Judy Shepard, Matthew’s mother, calls on Christians to support all human life and dignity, and I’m grateful for her witness. I encourage you to read her book, The Meaning of Matthew: My Son’s Murder in Laramie, and a World Transformed. On my brief drive from Denver to Laramie for the wedding this July, I listened to Judy Shepard narrate her audiobook.

Part of my choice to go to Laramie was to make a pilgrimage-of-sorts to the locations important to Matthew’s death. There was no denying its powerful connection to the Way of the Cross. In her book, Judy Shepard mentions that she is uncomfortable with overtly connecting Matthew to Christ, but I could not help but think of how the Virgin Mary would have told her own Son’s story.

“United with God, Matthew is forever a part of the Body of Christ and communion of saints. I imagine Matthew’s queer miracles show up quietly, most likely in the lives of other queer kids searching for belonging and among H.I.V. positive folks.”

As I drove west on I-80 and entered Laramie, I wondered if the rock formations concealed caves similar to Jesus’ after Golgotha or Ignatius’ at Manresa. My spirituality is Ignatian, and I felt consolation with Ignatius as my fellow pilgrim.

My first stop in Laramie was the bar where Matthew had his last beer and was picked up by his murderers. The bar has long since closed, and a restaurant and microbrewery now stand in its place. When I was still in high school, a member of my family took us there for lunch and simultaneously pointed out and laughed off its connection to Matthew’s death. My current pilgrimage was to honor Matthew and, with God’s grace, to help heal my own wounds as well.

At the brewery, I played the Cat Stevens song “Morning Has Broken” on the jukebox, much to the regulars’ chagrin. This was one of Matthew’s favorite songs, and his parents played it at his funeral. In 1998, Matthew had ordered a Heineken, but they were sold out when I visited. I love craft beer, so I enjoyed a tasty, summery IPA instead. When I went back to Boston at the end of the summer, I brought a can of this beer with me.

On the anniversary of Matthew’s death, I hope to enjoy a drink with one of my former professors who accompanied me through an independent study course, called “Queering the New Testament.” While taking it, my professor encouraged me to remove a few, more-traditional academic articles in order to make more time for me to prayerfully engage with Matthew’s story. On October 12 of this year, honoring Matthew’s memory with other queer folk will feel a little different. “Do this in memory of me,” indeed.

After lunch at the brewery, which now features Pride flags, I drove the short distance to where Matthew had been tied to a fence and left for dead. The exact location is on private property, so I pulled over as close as I could. After opening a bottle of Heineken I purchased at a locally-owned store on the way, I took off my shoes to put my feet on this holy ground. Making my own mother proud, I prayed a Rosary as I watched thunderclouds roll in from Laramie’s horizon.

After nearly 30 minutes, a woman drove by and turned onto the private road, which led to four houses. She stopped and asked what I was doing. To respect her right to peace and privacy, I mentioned that the spot was important to me and that I was just leaving. Her response surprised me.

“Well, some people come here for Matthew Shepard, but he didn’t die here. He did die nearby, though, and if you follow me, I can show you.”

I am so grateful for this angelic woman and her generosity. She shared powerful stories, which are not mine to offer here, and she invited me to share mine as well. Queer theology discusses the virtue of queer hospitality, and a stranger on the road offered this to me. Like the disciples on the journey to Emmaus, Christ was radically present in our encounter and conversation.

I did not journey the few hundred yards to the new fence (the original was demolished years ago) because several boys were playing nearby with paintball guns. Hunting is a way of life in Wyoming but I was deeply saddened to see the sacred site as a playground for young boys pretending to shoot each other.

Especially because of the United States’ current racial reckoning, and because the majority of anti-queer and anti-trans violence is perpetuated against trans women of color, my sadness was coupled with fear for a world actively debating which particular persons are granted the rights of respect, dignity and life itself.

Unable to visit the fence where Matthew had been left for dead, I went to the only public memorial site honoring Matthew’s life: a small plaque on a bench on the University of Wyoming’s campus. Pilgrims before me had left several flowers, now wilted; river stones, now covered in dust; candles, now melted and teddy bears, now aged from the sun and Laramie’s infamous wind.

This was another sign of our culture’s ambivalence toward the murder of queer and trans people. We are allowed to publicly mourn, but only briefly and quietly, with no system in place to keep the flowers fresh. No doubt Mary Magdalene gives us the strength to visit the tomb when others run and hide.

“This was another sign of our culture’s ambivalence toward the murder of queer and trans people. We are allowed to publicly mourn, but only briefly and quietly, with no system in place to keep the flowers fresh.”

I sat on Matthew’s bench and struggled to pray.

Here, I felt exposed and anxious. I rationally knew I was not in danger, but my spirit kept bringing me back to the feeling of having to hide my fear in plain sight, as people tossed Matthew’s story aside like society tosses aside queer and trans lives. St. Ignatius Loyola’s Autobiography discusses his scrupulosity and its connection to his struggles with prayer. Having asked Ignatius along for the ride on my pilgrimage, I asked him for help with my own diagnosed anxiety in this very triggering space.

The rest of the weekend, though, was joyous. I was able to celebrate my cousin’s wedding and, after the pandemic had kept us apart for years, revel in its love with my family. Three days later, before driving back to Denver, I walked to the location of the new fence. Respecting local property rights, I finally visited the site of Matthew’s murder. I want to say that it was the most powerful spiritual experience of my life, but it wasn’t. And that’s ok. As the Gospel of Luke says, “Why do you seek the living among the dead?”

At the final leg of my pilgrimage, I took the scenic route back to Denver. I chose to drive the road that Matthew often took between Wyoming and Colorado. I turned on Judy Shepard’s audiobook again and I scrolled to where I experienced love and grace within her story. Judy’s voice brightened when she described the creativity, nonviolence and hope at the roots of her community’s responses to Matthew’s death.

Matthew’s friends dressed as angels to shield his funeral from anti-gay protesters. Reporting on the reactions of Laramie residents, a few journalists were so moved they authored a play and a television film. Matthew’s parents created the Matthew Shepard Foundation, which works to “amplify the story of Matthew Shepard to inspire individuals, organizations and communities to embrace the dignity and equality of all people.” Personally, Matthew’s story inspires me keep studying and working to better support queer and trans kids.

While still on a life-long pilgrimage with Jesus, I close my story about this particular pilgrimage to Laramie with a reflection I wrote last fall for “Queering the New Testament”:

October 12th is the anniversary of Matt’s death, and I find myself called to make it a day of … I’m not sure. Prayer? Service? Action? The undergrads I work with on [the Boston College] campus are beginning a week of Pride activities and programs. I want to promote, engage and support them as best as possible.

On the 12th, [our office] is hosting a Pride Kick-Off Brunch, and I’m really proud that I was able to work with Campus Ministry to co-sponsor it! What better way to honor Jesus and Matthew Shepard than by working to make college campuses more welcoming to, and celebratory of, queer students?”

Matthew Shepard’s story calls us to “embrace the dignity and equality of all people.” In John 13:34, Jesus says, “As I loved you, so you also should love one another.” St. Ignatius calls us to show our love through our deeds. So, LGBTQ friends and family, is the Spirit calling you to put your love into action on your pilgrimage?