Towards a pastoral approach

What accounts for the Catholic Church’s recent focus on transgender people? Several US dioceses have recently issued documents on how Catholic institutions should respond to transgender people in parishes, schools and other institutions.

These include the Dioceses of Arlington, VA.; Springfield, Il; Milwaukee, WI; Fairbanks, AL; Lansing, MI; Salina, KS; Little Rock, AR; Indianapolis, IN; Denver, CO; and the Bishops of Minnesota, with the Diocese of Marquette, MI stating that transgender people cannot receive the sacraments unless they “repent.” Last year one US bishop claimed, “No one ‘is’ transgender.” Another bishop called the very idea of transgender people a “fundamental” mistake. Recently, a US bishop told me that one of his brother bishops believed that the US Conference of Catholic Bishops’ “highest priority” regarding church doctrine should be issuing a policy on transgender people.

These policies are having an effect. A friend told me that a transgender teen was distraught over being denied confirmation at his local parish. Some transgender Catholics are near despair at some newly restrictive policies, especially being barred from the sacraments. Christine Zuba, a transgender Catholic who serves as a Eucharistic Minister at her parish in New Jersey, told me, “Personally I often wonder why I am being singled out for such criticism and condemnation.”

The church’s emphasis on transgender people might seem to indicate a wave of transgender people flooding parishes or entering schools. But this is not the case, since only 0.6% of people identify as transgender, according to a 2021 Gallup Poll.

On the other hand, the topic is in the public eye, not only because of the increased visibility of transgender people, but also because several state legislatures have considered restrictions against medical care for transgender youth, with Governor Greg Abbott of Texas saying that certain medical treatments for transgender youth constitute “child abuse.”{{Mr. Abbot later called on Texans to report parents for making available to their children “gender-affirming” medical care. Criminal penalties were threatened before a Texas judge called a halt to the plan. Then, just last week, the Texas Supreme Court reversed the judge’s decision, allowing investigations of parents of transgender children to continue.}}

By contrast, NBC reported that many major medical organizations, including the American Medical Association, the American Academy of Pediatrics and the American Psychological Association, have concluded that “gender-affirming care is medically necessary for transgender youth and is backed by decades of research.”’

Still other studies suggest that those claims are far from settled, suggesting, as one priest described them to me, “low-quality evidence justifying high-confidence claims.”

Another question is why so many Catholic leaders began using the language of sin and repentance so quickly for a phenomenon that, at least publicly, is still so new, so little understood and still the source of so much scientific debate. How did the church move so swiftly to condemnation regarding a group who often say that they are striving to be whom God calls them to be, and who are severely at risk of suicide and self-harm, as well as violence and harassment, according to almost every report?

Amid these more restrictive approaches are signs of another kind of pastoral accompaniment. Last year Bishop Thomas Zinkula of the Diocese of Davenport instituted a “Gender Committee” to help his diocese reflect on the multiple issues surrounding transgender people, promising to listen to the experiences of transgender people as the diocese considers how best to minister to this community.

“The more we talked about it and met with people who are transgender or whose loved ones are transgender, we came to understand them a little better and how they were feeling. It was very humanizing,” the Rev. Thom Hennen, Davenport’s vicar general and pastor of a local parish, who also serves on the committee, told the Catholic Messenger, the diocesan newspaper.

“Our approach to this issue has evolved,” said Father Hennen. “We’re probably leaning toward developing a statement rather than a policy.”

A desire to respond pastorally

Since there is often little light and much heat on this topic, it would be helpful to consider the phenomenon of the transgender person, the concept of “gender ideology,” the current theological approaches, responses from US dioceses and what some other pastoral responses might look like.

I hope to offer a measured approach about a group of people, albeit small, who are very much misunderstood, often by their own church. For this article, I have consulted transgender Catholics themselves, those who minister to them, medical experts and parents; as well as bishops, priests, lay pastoral workers and theologians. I’ve also spoken to those who, broadly speaking, are critical of some claims made by transgender people and question the very notion of being transgender. I’ve tried to include and respond to some of their objections here. And I will also provide as many links as I can to original sources so that readers can review the data.

Let me state a few things at the outset. I’m not transgender. And there are some things about the transgender experience that I don’t yet understand. But I’ve become friends with several transgender Catholics, who have helped me to begin to see what their lives and experiences of God are like. I have also accompanied parents and families who have had a child (or sibling or spouse) announce that they are “transitioning.” What follows is my attempt to share what I’ve learned over the past few years and bring it into conversation with our Catholic faith.

Also, I’m not a theologian or a philosopher. So I don’t presume to set out any definitive philosophy or theology on this topic. Nor am I a physician, scientist or psychologist. So I don’t presume to know all the medical, scientific, and psychological answers to these questions, many of which are still hotly contested.

By the same token, the transgender Catholics I know are feeling great anguish, largely because of recent comments by church leaders, so I feel, like many Catholics, a desire to respond pastorally to their situation.

It was heartwarming when two women stopped, pushing a stroller with a very young set of twins. They asked ‘Where can we get our girls baptized?’ and we were able to provide them with some options.“

Some basic facts

A transgender person is someone whose inner experience of their gender does not fit with the sex that they were “assigned” at birth. (In this context, “assigned” means what the physician or hospital recorded on the child’s birth certificate.){{A transgender person is distinct from a person with intersex conditions, that is, someone born with combinations of reproductive or sexual organs, hormones, or chromosomes that do not fit the traditional definitions of male and female. Some studies suggest that approximately 1 in 1,500 people are born with ambiguous genitalia, and that up to 1.7% of all people have some form of intersex condition. Some intersex persons also identify as transgender, and some transgender persons consider transgenderism to be a form of intersex condition.}}

Many transgender people experience what is called “gender dysphoria,” which the American Psychiatric Association describes as “psychological distress that results from an incongruence between one’s sex assigned at birth and one’s gender identity.” The APA also notes that while gender dysphoria often begins in childhood, “some people may not experience the condition until after puberty or much later.” Finally, as the APA states, nodding to the variety of experiences, “Not all transgender or gender diverse people experience dysphoria.”

Some argue that increasing numbers of transgender people may be a response to peer pressure or media images, especially among youth. (The number of teens who identify as transgender has been on the rise in the past few years.) One distraught parent with whom I spoke this year believed that his teenage child, who had announced his transitioning, was just trying to “fit in,” “gain acceptance” or “be seen as cool.”

While this may be the case for some younger people coming to understand their sexuality or seeking peer approval, most transgender adults say that they were not influenced by external forces, peer pressure, or media encouragement, much less “gender ideology.” Rather, they report they are responding to often decades-long feelings of deep dissatisfaction with their gender.{{A study published this month concluded that few transgender children change their minds about their transitioning after five years. But, as the New York Times reported, “[B]ecause the study began nearly a decade ago, it’s unclear whether it reflects the patterns of today, when many more children are identifying as trans.”}}

“For as long as I can remember,” said Christine Zuba, “since about the age of three or four, I felt different. As a child, I would go to bed every night praying that I would wake up as a girl.”

Colt St. Anand, M.D., Ph.D., a physician and psychologist who works with transgender people, told me, “Ever since I could communicate, I knew I was different, but I did not have the language to communicate that difference. I knew that I was not a girl.”

Sister Luisa Derouen, OP, a Catholic sister who has ministered to the transgender community since 1999, said this when asked about the influence of peer pressure on young people: “I’m sure this is real, but not nearly as much as people want to believe. Also, very many young children declare that they are transgender long before they’re influenced by peers or the media.”

Others have pointed out that transgender people, including transgender youth, have always been part of humanity, and in various cultures, though it has only been relatively recent that their presence has become known more broadly. Thus, the phenomenon, which seems new, may be less a reaction to external forces and more of an equilibrium reached after years of denial.

Treatment for transgender people varies from basic mental health assistance to hormone therapies that delay (but do not eradicate) the onset of puberty, to more long-lasting and significant interventions for adults, like surgery (breast reductions, removal of Adam’s apples, etc.) Every expert, however, points out the need for professional medical and psychological care for transgender people. By the same token, the denial of all medical care to transgender youth, as Governor Abbott has suggested, might prevent even psychological counseling for young people, who need it the most.

Among the more controversial treatments are hormone therapies for youth, sometimes called “puberty blockers.” Many argue strongly against their use, primarily because the long-term side effects are still unknown. Others point out that they are reversible, “largely considered safe for short-term use” and an alternative to surgery, giving parents and youth more time to wait and discern. They also reduce rates of depression and suicide. A study in the Journal of the American Medical Association indicated that they reduce depression by as much as 60% and suicide by as much as 73%. Other experts take a more neutral view. In general, most physicians suggest exercising great caution for the treatment of teens.

Researching transgender issues brings one into contact with wildly different perspectives, with each side contradicting the other with different experts and different sets of data. Perhaps the most extensive survey came in 2018, when Cornell University looked at 55 peer-reviewed, English-language studies published from 1991 to 2017, and concluded that 93% of these studies found that “gender transition improves the well-being of transgender people, while 4% report mixed or null findings. We found no studies concluding that gender transition causes overall harm.”

Sivagami (Shiva) Subbaraman, the founding director of Georgetown University’s LGBTQ Resource Center, said this to me about her work with transgender youth: “I’m no expert on transgender people, but all I know is that before these students transition, they are miserable and despairing and afterwards they are happy and at peace.”

Still, the debate rages.

What is “gender ideology”?

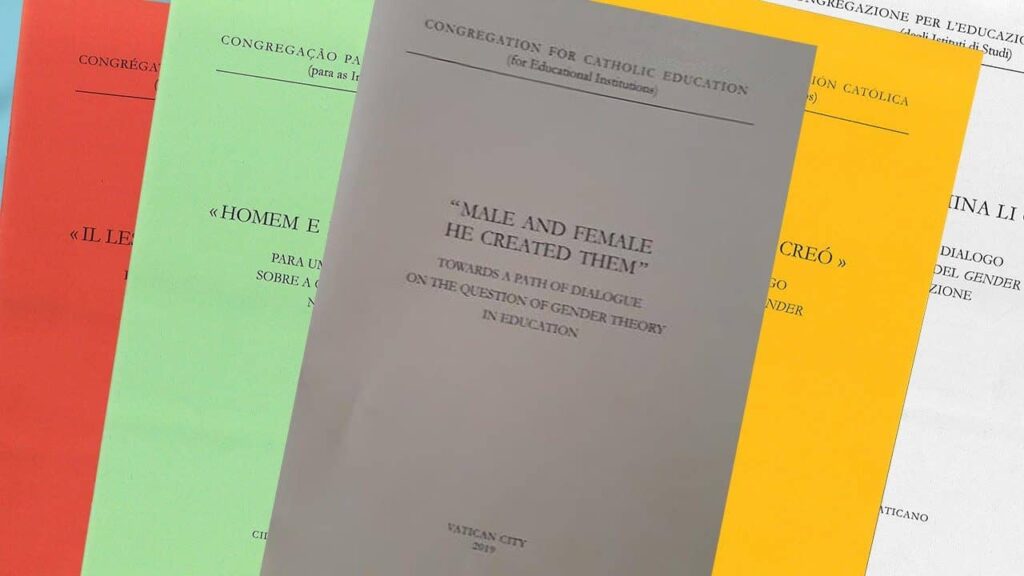

The more one reads church policies, the more one runs across the concept of “gender ideology” or “gender theory,” almost always presented as a grave danger. In “Male and Female He Created Them,” a document written by the Congregation for Education and designed primarily as a series of guidelines for schools (rather than an overarching Vatican policy), gender theory is mentioned several times.

“Gender ideology,” however, is a vague term that can mean many things to many people. As the Catholic theologian Daniel Horan, OFM, has written, “Among the many troubling aspects of this derogatory phrase and the agenda it represents is the ambiguity of the term itself. There are no two sources that agree on what precisely ‘gender ideology’ means.”

The term could mean any or all the following things: a person’s gender has no connection to their biological sex; a person’s gender has priority over biological sex; a person’s gender can be changed by that person’s choice; it is desirable to abolish the whole notion of gender and replace it with a “spectrum;” gender is a choice and physical bodies have no meaning; even that there is no objective truth given by God.

But not all transgender people ascribe to all, most or any of these beliefs: “There may be some people who ascribe to these beliefs, but it is possible to be transgender and disagree with all the above statements,” said a Catholic transgender man with a Ph.D. in theology. (My friend wants to remain anonymous because he has not yet shared his transgender status publicly.)

Regarding “gender ideology,” he said, “Most transgender people, though not all, consider ourselves male or female and rejoice in that identity. I know no one who is transgender because they believe that gender should be eliminated or sexual differences do not exist.”

Every transgender adult with whom I’ve spoken rejects the idea that “gender ideology” is behind their experiences. While the case may be different for youth who may be more prone to peer pressure (or media imagery), the transgender adults with whom I spoke reject the notion that they are the result of an ideology, much less one they don’t agree with. “I had never heard of ‘gender ideology’ until the church began using it,” said Christine Zuba. The term is often used, then, as a weapon against transgender people.

Some argue in response that the claims of transgender people can and even should be evaluated based on how they cohere logically and with competing metaphysical and epistemological claims. It is analogous to feminism, the argument goes. One priest wrote this to me, after reading the above: “Women are not created by feminism. Rather, feminism is a system of ideas that claims to describe the reality and experience of being a human female. Inasmuch as those claims are a system of ideas, then feminism is an ideology.” But, as this priest argued, “it is possible and in fact desirable to maintain that the experience of women, on the one hand, and feminism as an ideology, on the other, are both distinct and related.”

In the case of transgender people, however, most do not seek to make metaphysical or epistemological claims, but simply ask that the church take their experiences seriously. One could respond to that by asserting themselves as transgender they are implicitly making such claims, but most transgender Catholics will tell you that they are simply asking for the church to listen to them and to trust them.

The transgender people with whom I’ve spoken do not see themselves as promoting, embodying or assenting to a “system of ideas.” Others may perceive them as doing so, but those who would see them purely from an intellectual standpoint should be invited to listen and accompany them. Rather than seeing them as categories or stereotypes, or as purveyors of an ideology, transgender people invite us to see them as individuals who deserve to be listened to.

As Ray Dever, a Catholic deacon and the father of a transgender child, wrote these lines in US Catholic which I quoted to Pope Francis during our audience in 2019: “Anyone with any significant first-hand experience with transgender individuals would be baffled by the suggestion that trans people are somehow the result of an ideology. It is a historical fact that long before there were gender studies programs in any university or the phrase gender ideology was every spoken, transgender people were present, recognized, and even valued in some cultures around the world.”

Hilary Howes, founder of Transcatholic, a support group for transgender Catholics, also disputes the notion that the trans person is the result of “gender ideology.” “There is every evidence that this has happened throughout history and in every culture,” she said. “It is not a product of recent theories but a 21st-century culture of honesty and openness that allows us to be recognized in our modern world.”

Kay, the mother of a transgender son, whose story is included in a study commissioned by the Catholic Health Association, believes that “gender ideology” had nothing to do with who her son is. As the mother of a little girl, Kay was shocked when her two-year-old said, “I’m a boy.” At the age of four, her child wept when told she was a girl like her mother.

After years of trying to discern how to help her child, including following the advice of a therapist to insist that her child engage in more traditional girl behaviors (“If she goes to a party, insist she pick the pink balloon”), she saw her child fall into serious depression. Eventually, the child began publicly identifying as a boy, a decision that Kay accepted. Today, Kay reports that her son is a “very bright, happy and well-balanced young man.”

Later, their bishop ended transgender medical care at the local Catholic hospital, saying that her son’s identity was a result of “modern culture” and “a momentary desire provoked by emotional impulses” of self-will. As Kay says, “My story proves that [that] opinion could not be more wrong.”

Thus, the term “gender ideology” does not reflect the experiences of transgender people and should not be used to understand or evaluate them, much less as a weapon against them. Sister Jeannine Gramick, SL, co-founder of New Ways Ministry, who was recently praised by Pope Francis for her 50 years of ministering to LGBTQ Catholics, says, “’Gender ideology’ is a wound to transgender people because these words do not respect the concrete lives they have suffered. We need to stop using these hurtful words.”

Grave danger

To that end, one US bishop told me that the key to understanding some of the church’s resistance is rooted in the concept of the danger of gender ideology and the danger of transgender people.

“The question of the grave danger that so many bishops perceive in these issues is fundamental to generating the stance of exclusion so many bishops are taking” he said.

“Once one buys into this mindset of danger,” he said, “the chances for vindicating a truly pastoral approach are greatly diminished. Bishops who perceive danger are focused on the culture as a whole and the belief that using the transgender experience to understand the general realities of sex and gender will confuse and mislead large numbers of young people who are not transgender. This is a difficult question. We must ask whether our society is on a trajectory of positing a generalized stance of ‘plasticity’ about sex that is not reflective of the general human experience. But we must also show great pastoral sensitivity to transgender youth and adults.”

So what is the way ahead, according to this US bishop?

He also pointed to the Diocese of Davenport, whose way of proceeding he said, shows us a path. “It is a reflection on the pastoral wisdom of Bishop Zinkula’s approach,” he said. “It is a position rooted in the pastoral praxis of Jesus. And that, in my view, is the strongest foundation for any defense of the rights and dignity and worthiness of transgender persons in the life of the church and society.”

“Male and Female He Created Them”

One of the most surprising developments about the transgender experience is how quickly a theology about them has developed within the church, when there is so little known about its origins.

As I mentioned, the most comprehensive statement is the Congregation for Education’s “Male and Female He Created Them.” The document was intended as a list of general guidelines for schools, not for parishes and not for the whole church and not as a final church teaching on the matter. Yet in the absence of any other substantial theological reflection from the Vatican, that document has come to the fore. So it deserves our attention here.

The congregation’s document should be praised for its call for “listening” and “dialogue.” The subtitle is important: “Towards a Path of Dialogue on the Question of Gender Theory in Education.”

It is an explicit call for dialogue, which all should welcome. It speaks of a “path,” which indicates that the church has not yet reached the destination (even though some are using this document now as an almost magisterial teaching). It focuses on the “question” of gender theory in education, which leaves some degree of openness, and is addressed mainly to educators and formators, including those responsible for the training of priests and members of religious orders.

The crux of the congregation’s argument is in its understanding of gender: “This separation [of sex from gender] is at the root of the distinctions proposed by different ‘sexual orientations’ which are no longer defined by the sexual difference between male and female and can then assume other forms determined solely by the individual, who is seen as radically autonomous.”

One objection to that proposition is that, again, it sets aside the real-life experiences of transgender people. In fact, the document’s primary partners for conversation seem to be philosophers, theologians and older church documents and papal statements—not biologists or scientists, not psychiatrists or psychologists, and not LGBTQ people and their families.

The congregation also suggests that discussions about gender identity involve an intentional choice of gender by an individual. But, again, people who are transgender report that they do not choose their identity but discover it through their experiences as human beings in a social world. Sister Luisa Derouen, with her decades of experience with transgender Catholics, says. “They are not transgender because they are sinning, rejecting God, acting on superficial whims or delusional.”

Again, the document also neglects to engage in discussions about new scientific understandings and discoveries about gender. It relies mainly on what one Catholic moral theologian described to me as “biological reductionism”: the belief that gender is determined solely by one’s visible genitalia, which contemporary science has shown is not always an accurate way to categorize people. Gender is also biologically determined by genetics, hormones and brain chemistry—things that are not visible at birth. The congregation’s document relies heavily on categories of male and female that were shaped centuries ago, rather than with more contemporary scientific methods.

Another troubling aspect of the document is the way it frames transgender people. Consider this passage: “This oscillation between male and female becomes, at the end of the day, only a ‘provocative’ display against so-called ‘traditional frameworks,’ and one which, in fact, ignores the suffering of those who have to live situations of sexual indeterminacy. Similar theories aim to annihilate the concept of ‘nature’ (that is, everything we have been given as a pre-existing foundation of our being and action in the world), while at the same time implicitly reaffirming its existence.”

In this formulation, transgender people are being “provocative” and are (either consciously or unconsciously) trying to “annihilate the concept of ‘nature.’” Family members who have accompanied a transgender person through their attempts at suicide, their despair over fitting into the larger society, or their struggles to believe that God loves them, will find that sentence baffling—and even offensive. Sister Luisa told me recently, “Many transgender people have done the hard work of self-knowledge more than most of the rest of us.”

In 2019, when I met with the prefect of the Congregation for Education, Cardinal Giuseppe Versaldi, we had a warm meeting in which I shared with him and the congregation’s undersecretary three letters: one from a transgender Catholic man, one from the Catholic parents of a transgender youth and from Sister Luisa Derouen. After our meeting, Cardinal Versaldi permitted me to share publicly his sorrow “if people thought the Congregation was accusing people of being ideologically distorted.” Further, he wished “to share their care for transgender people and want to continue dialogue to reflect on their experiences.”

Cardinal Versaldi’s words are an admirable goal for the church. And dioceses like Davenport, with its Gender Committee and listening sessions involving transgender people, also show a path by fostering dialogue to help the church “reflect on their experiences.”

Current approaches in US dioceses

The theological underpinnings of most of the church’s responses, especially in US dioceses, relies not only on the Congregation of Education’s document, but more broadly, on Scripture and what one moral theologian described to me as “narrow” interpretations of the natural law.

The Diocese of Marquette states: “Because of the fundamental body‐soul unity of the human person, the sex of the person and the sex of the body are the same. Every one of us is created as either male or female.”

The Diocese of Arlington states, “The claim to ‘be transgender’ or the desire to seek ‘transition’ rests on a mistaken view of the human person, rejects the body as a gift from God, and leads to grave harm.”

Once again, statements that there are only males and females not only goes against scientists who state that there is a much wider range in human biology, it also sets aside the experiences that transgender people report: the deep feeling that the “sex of the person” and the “sex of the body” are not the same for them, sometimes since early childhood.

Since the theological and philosophical categories used do not reflect the experience of transgender people themselves, it is difficult to square the dioceses’ desire to offer compassionate and intelligent responses to this group of people when something so fundamental is overlooked. Sister Jeannine Gramick said, “Transgender people are not abstract; they are not a philosophical or ideological system. A transgender person does not decide abstractly if she (or he) should be a man (or a woman).”

Most diocesan policies so far proceed from those theological reflections and then restrict entrance of transgender children to schools, prevent church employees from using “preferred pronouns,” even going as far as to bar transgender people from the sacraments, often using the language of sin and repentance.

The Diocese of San Antonio says that if a student’s “expression of gender, sexual identity, or sexuality” causes “confusion or disruption at the school, or if it should mislead others, cause scandal, or have the potential for causing scandal,” then the matter is to be brought to the student and parents. If that doesn’t effect a change, then the student “may be dismissed from the school, after the parents are first given the opportunity to withdraw the student from the school.”

The Diocese of Springfield states, “All employees and volunteers will be addressed and referred to with pronouns in accord with their biological sex.” Violation of this policy by any employee will bring “immediate corrective action, suspension, and possible termination of employment.”

Another way of looking at these questions from a theological standpoint might be as follows: God has created people in a multiplicity of ways, both in terms of biology and psychology. And we understand human sexuality in different ways than did the Book of Genesis. Natural law, after all, reminds us that by looking at the way God created the world and how nature reveals God, we can deduce God’s designs for the world and for humanity. Most Catholics now understand this in terms of homosexuality, with most people accepting the fact that, as Pope Francis said to Juan Carlos Cruz, a gay man, “God made you this way.”

By contrast, diocesan policies or bishops’ statements that condemn or deny the existence of transgender people, seem to say, “Based on our theology, this shouldn’t be happening in nature. Our human anthropology, based on what we knew in the past, is clear: God would not let this happen.”

Another theological approach might be to ask, “Based on what we see in nature, how can we deepen our theology and philosophy? What new things can we learn about our human anthropology? What is God revealing to us now?”

“A proper document would embrace the conclusions of the scientific and medical communities that shows our gender develops in the womb and in a percentage of the population there is a mismatch between the two,” said Hilary Howes.

Church documents might start with what is rather than what theology tells us should be.

Again, the Diocese of Davenport, with its listening sessions, provides a useful model of Christian praxis. According to the Catholic Messenger, members of the Gender Committee have “studied the terminology, latest research, networked with others in the Church on the forefront of this ministry and listened to stories of transgender persons and their families.”

“Persons who identify as transgender or gender non-conforming are our children, siblings, parishioners, neighbors and friends,” said Marianne Agnoli, coordinator of the group. “They do not experience the same deep psychological and physiological association between sex and gender that most men and women experience. While this is not a new phenomenon, our greater awareness of it is new.”

Towards a pastoral approach

So far, the pastoral approach of most US dioceses has been to bar, restrict or condemn transgender people out of a fear of giving into “gender ideology,” or even promoting child abuse, rather than to listen to transgender people and their families. Because these fears have led to draconian, restrictive and even cruel policies, transgender people, who have not had much if any say in the formulation of these policies, have felt targeted by the church that they look to as a home.

Most diocesan policies began by talking about “accompaniment” and a desire for a pastoral approach. The Springfield Diocese says, wisely, “For the parents of a child who is dealing with this [transgender] condition, the first priority must be to assist the child in this difficult situation.” Most diocesan statements begin by expressing a genuine care for transgender people.

But nearly all these policies move quickly into condemnations of “gender ideology” and set forth sweeping restrictions on transgender people. The door is opened and then slammed shut.

Often highly detailed, these policies focus on pronouns, bathrooms and dress codes and then move to weightier matters: entrance into schools and inclusion in the church itself. The Diocese of Marquette’s policy reads: “A person who publicly identifies as a different gender than his or her biological sex or has attempted ‘gender transitioning’ may not be Baptized, Confirmed, or received into full communion in the Church, unless the person has repented.”

As Sister Luisa told me, “It is impossible to show respect for transgender people while at the same time denying their own experience of their lives and insisting they don’t exist.”

What might be some more pastoral ways to move ahead?

Let me propose a few urgent steps.

Wait. To say that waiting is urgent sounds paradoxical, but there is an immediate need to set aside the current temptation to judge, declare and teach, when so little is still understood about the transgender identity, and, moreover, so many are at serious physical risk from persecution and harassment.

Violence against transgender people is at an all-time high, with 50 transgender people killed in the US in 2021. (Sister Luisa suggested that number might be artificially low, given the embarrassment that still makes it hard for people to admit that a murdered family member was transgender.) Suicide and self-harm are also endemic among trans youth, with an astounding 82% having considered suicide and 40% attempting suicide, according to a study in 2020. Public policies and statements that cast transgender people as sinners or, worse, in need of repentance are the last thing the church needs to issue. It contributes to an atmosphere of vilification and violence.

Thus, waiting may be the most important thing that the church can do right now. There is nothing wrong with saying, “We don’t know right now. We are learning. And before we issue any policies, we need to understand more about this community.” Before the church can be an ecclesia docens (a teaching church), it must be an ecclesia discens (a listening church.)

The primary danger in rushing out condemnatory policies is that they will vilify a group of people precisely when they most need support. It will also reify early and perhaps faulty evaluations of a phenomenon that may take scientists, medical experts and theologians decades to understand fully.

Moreover, policies should resist excluding a group of people who are already excluded from society. “I hope and pray,” said Deacon Ray Dever, the parent of a trans child, “that we do not rush to any decisions that effectively exclude transgender people from Catholic institutions.” We should be walking with the excluded, not excluding them further.

A final danger is the alienation of youth–and not just transgender youth. According to a recent Pew Survey, some 53% of people between 18 and 29 know transgender people, and that number is probably higher for high school students. My own conversations with high school classes from around this country, mainly in Catholic schools, tell me that young people take a dim view of those who would try to condemn or vilify their classmates, not to mention their brothers or sisters.

Listen. “Before they say another word about transgender people or gender identity, the US bishops needs to show significant evidence that they have listened to a wide range of experiences from persons for whom gender is a question,” said Francis De Bernardo, co-director of New Ways Ministry. “They also need to show that they have read, studied and seriously considered the scientific and social scientific research that supports positions that challenge gender binary.”

My Catholic transgender Ph.D. friend said, “Transgender people are the primary sources for understanding this phenomenon. I beg bishops to speak to ten, if not a hundred, transgender people and really listen.”

James F. Keenan, SJ, a moral theologian at Boston College, agrees, seeing listening as an urgent need, especially for the hierarchy. “That means learning humility and learning to listen, especially to those people who are being terrorized not by the question they are facing but by the moralistic deafness of the church that thinks “it knows everything better than others.”

Besides meeting with transgender people themselves, as the Diocese of Davenport has done, there are other resources that could help church leaders. The Catholic Health Association recently published a helpful booklet, in which they gathered a group of five Catholics – two transgender persons, two parents of transgender children, as well as Sister Luisa Derouen, with her 20 years of ministering among members of the transgender community.

Another way of listening is to read testimonies from not only transgender people themselves, but those who already minister to them in the church, like Sister Luisa in the US, who has written about her ministry; Sister Monica Astorga, an Argentine nun praised by Pope Francis for her ministry to transgender people; and Sister Prema Chowallur, who works with transgender people in the slums of India; as well as with Catholic parents like Deacon Ray Dever. Catholic theologians who have written on the topic, like the Rev. Bryan Massingale of Fordham University; Daniel Horan, OFM, of St. Mary’s College; Craig A. Ford of St. Norbert College; Lisa Fullam, until recently of the Jesuit School of Theology in Berkeley; and James F. Keenan, SJ, of Boston College, can also be conversation partners. Also, a recent statement by Dennis Holtschneider, CM, the president of Association of Catholic Colleges and Universities, which urges “kindness,” is helpful.

The Diocese of Davenport again stands out in this regard. Bishop Thomas Zinkula has taken the time to learn from and talk with transgender people, their families and professionals. Father Thom Hennen, the vicar general for the diocese, who has been a part of this process, wrote in the Catholic Messenger, “There is good consensus, for example, that gender dysphoria is real, that transgender people are not ‘pretending.’ Individuals do not choose to be transgender, at least in terms of the experience of this deep disconnect between their bodies and their perception of themselves.”

More importantly, Father Hennen wrote, “The fact is, we do not have a perfect or near complete answer to this question, not in our diocese and not in the Church as a whole.”

In his column in the Catholic Messenger, Bishop Zinkula explained his diocese’s approach: “It is important to get to know people who experience gender dysphoria before jumping to conclusions. Our Christian faith calls us to love people. We cannot love them in the abstract. Love begins with personal encounter, with hearing someone’s story. Having a transgender acquaintance, friend, son, daughter, brother or sister guides the heart and gives one a more informed perspective on the topic.”

“The work of the committee,” continued the bishop, “is not about undermining Church teaching. It is about engaging a group of people who are on the margins, listening to them, accepting them as persons, accompanying them, loving them. That is the starting point to everything the Church does.”

Do not judge. With ongoing research, new discoveries and increasing numbers of personal testimonies about the transgender experience being shared–as well as the fact that transgender people are under attack–the last thing that bishops should do is issue policies that are condemnatory, restrictive or punitive. In other words, the church should listen to Jesus who says, “Judge not.”

Part of this judging is not telling transgender people that they are the result of sinful or selfish choices, abandoning God, destroying the family, “annihilating” the concept of nature, merely bowing to peer pressure or giving in to “gender ideology.” The last phrase, which Sister Jeannine described as a “wound to transgender people,” is especially unhelpful.

Do not bind. Setting binding policies now, especially restrictive and punitive ones, for an entire diocese, much less an entire country or an entire church, removes from the individuals involved in decisions about transgender people—bishops, pastors, pastoral associates, educators and parents—the ability to use the latest scientific, medical and psychological data, which are updated almost weekly. To that end, Sister Luisa, the Catholic in this country with perhaps the most experience ministering to transgender people, said, “The USCCB should not make general, binding policies on all Catholic institutions.”

Even well-meaning documents and policies about a medical condition still being studied will set in stone misguided responses when the church needs to continue learning. Here, discernment is key: looking at the situation on a case-by-case basis; reflecting on what scientific, medical and psychological experts say; prayerfully considering what is best for the individual and the parish or school; and then deciding. Binding statements based on old understandings of biology, Bible passages that could not have anticipated current-day realities and theological categories unable to encompass the human experiences of this newly public group of people, will prevent decision-makers (as well as families) from coming to well-informed and compassionate decisions based on the latest data.

Advocate. Transgender people are among the most marginalized people in society and surely the most marginalized group in the church today. As I’ve mentioned, they are at a severe risk of harassment and beating, as well as suicide and self-harm. In much of Western society, there are moves towards welcoming gays and lesbians, but in most places the door is shut for transgender people. As I see it, most of the world treats transgender people today the same way that it treated gay people 50 years ago: with confusion, rejection and disgust.

So it is important for the church to be clear about standing with this group that is on, as Pope Francis said, “the peripheries,” not judging them but advocating for them. This is an at-risk minority that needs our accompaniment and support, not our judgment and condemnation. In his public ministry, Jesus continually stood with the most marginalized, the most vulnerable and the most rejected. And there are few groups more marginalized, vulnerable and rejected than the transgender community.

“The heart of this church”

The comments of Cardinal Wilton Gregory, Archbishop of Washington, D.C., to a transgender person in 2019, are a good place to end.

At a “Theology on Tap” gathering in Washington, a person named Rory asked him, “What place do I as a confirmed transgender Catholic and what place do my queer friends have here in this archdiocese?”

“You belong to the heart of this church,” said Cardinal Gregory.

“There is nothing that you may do, may say, that will rip you from the heart of this church,” he continued. “There is a lot that has been said to you, about you, behind your back that is painful and is sinful….We have to find a way to talk to one another, and to talk to one another not just from one perspective, but to talk and to listen to one another. I think that’s the way that Jesus ministered. He engaged people, he took them where they were at, and he invited them to go deeper, closer to God. If you’re asking me, where do you fit? You fit in the family.”