The Catholic Church, LGBT people, and memory

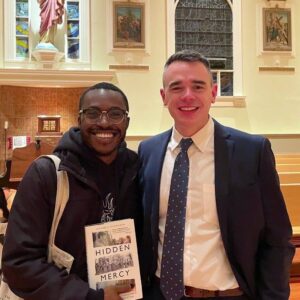

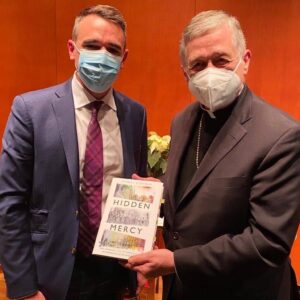

During a recent visit to the University of Notre Dame, a student approached me. She told me that she had stopped engaging with her faith and though she didn’t specify why, I had just finished a dialogue about my new book, Hidden Mercy: AIDS, Catholics, and the Untold Stories of Compassion in the Face of Fear, which includes an exploration of my own experience as a gay Catholic.

The young woman told me she hadn’t felt like there was a place in the church for her, so it was safe for me to assume she was one of the many Catholics who identify as part of the LGBT community. She would be graduating in a few months and had secured a position working in HIV and AIDS care. Someone had given her a copy of Hidden Mercyand though she was at first reluctant to spend time reading a book about Catholicism, she decided to give it go.

When she finished the book, she was “blown away,” she told me, by the stories of ordinary Catholics, many of them also LGBT, who responded with mercy and compassion to people living with HIV and dying from AIDS in the 1980s and 1990s. Stories of priests, sisters, and LGBT Catholics who opened clinics for people with AIDS, set up buddy programs, visited the abandoned in hospitals, they offered her consolation that had previously been denied to her.

She hadn’t known any of this history. But she is hardly alone.

For the past few months, I’ve been on the road, sharing stories from Hidden Mercy at parishes, high schools, and universities. I’ve had the opportunity to hear from a range of Catholics, including many LGBT people, plus their friends and families, who are eager to understand their place in the church today. And like me, they are finding through these stories much needed encouragement that they are indeed welcome in this institution.

As a gay reporter covering the Catholic Church, I’m familiar with the many challenges facing LGBT people of faith. Confusing and sometimes hurtful comments from church leaders. High-profile firings on LGBT employees from parishes. And even moments of pain that never make the news, like a harsh word from a priest during a funeral or strained relationships with disapproving parents.

But through my reporting, I am also familiar with the countless individuals who have fought to make the church live up to its Gospel values by encouraging all the faithful to be more fully welcoming.

Over the course of writing Hidden Mercy, and then through the nearly three-dozen book events since its publication, I’ve learned a number of lessons about LGBT people and the Catholic Church today. Let me share a few of them.

A debt of gratitude

First, I’ve learned that any Catholic space where LGBT people feel fully welcome is not an accident. No matter how obvious it seems today, even the most open-minded parish was not always that way. And we owe a debt of gratitude to generations of LGBT Catholics who came before us.

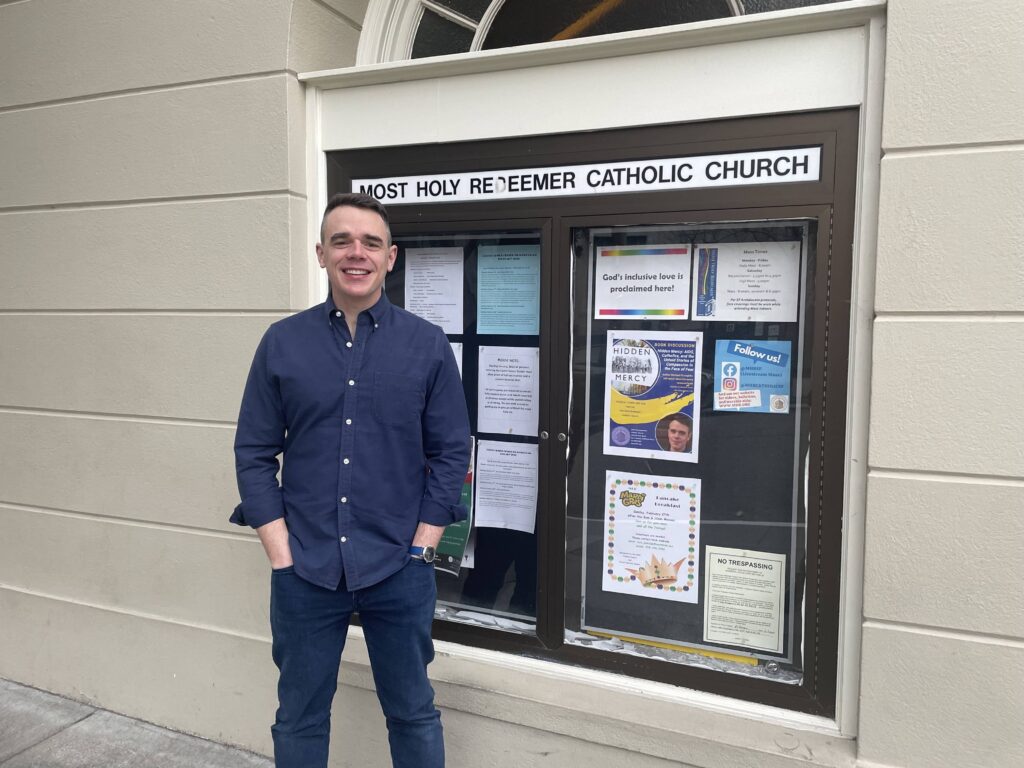

Take Most Holy Redeemer Parish in San Francisco.

At first glance, it’s easy to think that a parish located in the middle of San Francisco’s iconic gay neighborhood, the Castro, would be welcoming to LGBT Catholics. How could it be otherwise?

That was my impression the first time I visited. I had noticed glassed-in bulletin boards outside the main entrance. They contained flyers covered in rainbows. One said, “God’s inclusive love is proclaimed here.” Another depicted an upside-down pink triangle. Written in big block letters, the flyer reads, “Stop the Violence. Safe place.” I had noticed them posted on windows of gay bars, bookstores, and cafés throughout the Castro. It was heartening to see one displayed at a Catholic church.

But as I dug through the parish’s history, I learned that it took a group of committed gay Catholics, as well as open-minded grandmothers—or the “gays and the grays” as a forward-thinking pastor put it—to create the kind of community that would go on to be a beacon for all kinds of marginalized communities over the coming decades.

As the 1980s wore on and HIV and AIDS affected more people in the Castro, a small group of gay men who belonged to Most Holy Redeemer suggested that their parish had a moral obligation to respond.

Working together, the young gay parishioners and the elderly widows set up a neighborhood buddy program to help with everyday tasks like laundry and cooking. When parish leaders asked the gays for help, many simply couldn’t change their work schedules. But what about the grays? They were retired and certainly had time. And many of the widows were pretty good cooks. Would they be willing to help a community whose lives seemed so different from their own?

Many of the Irish and Italian grandmothers who had stuck around during the lean years at Most Holy Redeemer, and who reveled in the renewed community created by the influx of gay men, responded with gusto when they saw the great need that resulted from AIDS. The grays cooked meals. They dropped off food. They sat and listened.

A community that today still thrives and serves a large population of LGBT Catholics was never inevitable. And if we forget this history, we risk losing these spaces. The fight to maintain welcoming spaces, and to create new ones, will never be over.

Leading with humility

Second, the church thrives when its leaders have the courage and confidence to lead with humility.

Smack dab in the middle of Greenwich Village, Saint Vincent’s Hospital has a history as colorful as the generations of women who staffed its wards, the Sisters of Charity of New York. But the hospital is perhaps most known for its compassionate response to the HIV and AIDS crisis in the 1980s and 90s. Again, it would be easy to think that it responded well simply because it was located in an area that was home to a large gay population.

The actual story of how Saint Vincent’s Hospital came to provide a refuge for gay men dying from AIDS is more complicated than I first imagined. A Catholic hospital in the 1980s didn’t transform overnight into a place where gay men felt comfortable during particularly vulnerable moments. In the end, many received excellent medical care, and eventually the hospital treated them better than many other parts of society had.

But that reality required time and effort. It took Catholic sisters who were committed to learning how to serve a particular community and queer activists who refused to settle for less than what they deserved. The give and take between these two seemingly at-odds groups resulted in what would become one of the finest AIDS clinics anywhere in the United States.

Sister Karen Helfenstein, a Sister of Charity of New York, worked at Saint Vincent’s first as a nurse, and by the time AIDS was a major crisis, as the vice president for mission. She remembers learning that the LGBT community didn’t feel welcome at St. Vincent’s, in part through a series of protests targeting the hospital by the radical activist group, ACT UP.

What, exactly, was the message the protesters were trying to send? Sister Karen decided the best way forward was to do what she had done with the cardinal’s office and with the medical staff. She would listen.

“We need to talk with them, and we need to see what we can do, learning from them what their needs are,” Sister Karen told me.

That radical act of humility, listening to a community in need rather than digging in and refusing to budge, helped lead to a transformation.

Sister Carol’s story

Finally, younger LGBT Catholics have much to gain through intergenerational friendships, with LGBT people and allies who have experience, wisdom and insight.

One of the main profiles in Hidden Mercy chronicles Carol Baltosiewich.

Formerly a Hospital Sister of St. Francis, Carol was one of the first people I met as I began researching this topic. She was featured in the America Media podcast series, Plague. Though her story has many twists and turns, it is ultimately one of an individual who confronted AIDS and rather than turn away from the crisis in front of her, responded with love and mercy. She overcame her own biases, listened to the needs of a community she didn’t understand, and transformed into an ally in the fight against HIV.

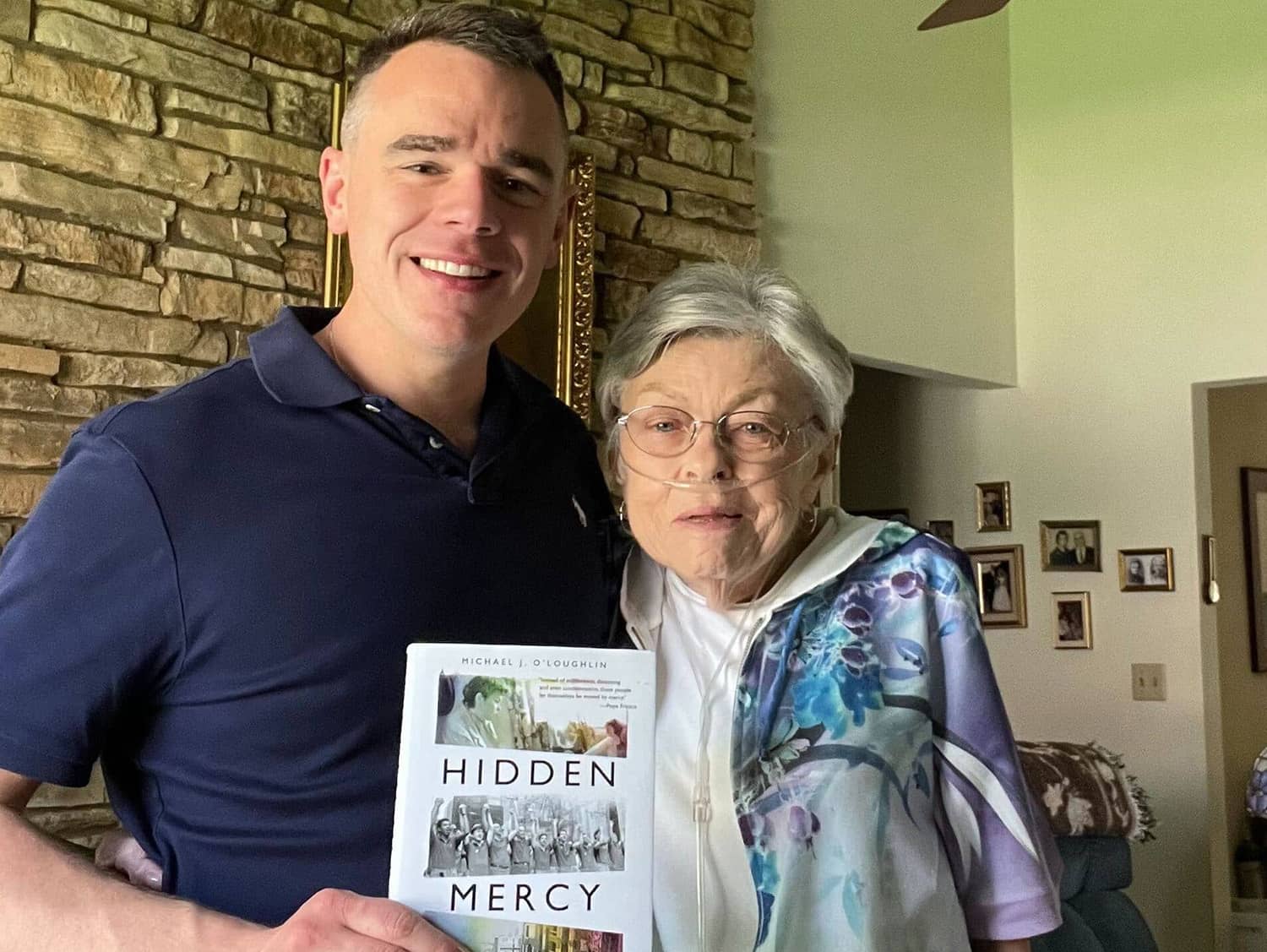

I recently delivered a talk in St. Louis and while I was visiting, I rented a car and drove across the Mississippi River to Carol’s home in Belleville, Illinois. We had met a few times previously, talked on the phone countless times, but I hadn’t seen her since the book was published. I stopped to pick up some coffee, and a few truffles, and made my way to her apartment. We hugged and sat down at her small dining-room table.

She told me she was pleased with the book—a relief to hear, as she had been so generous in sharing her life story with me and I had felt great pressure to get it right. She told me that she had been in touch with old friends and colleagues, who had read my book or my op-ed in the New York Times that highlighted a letter Pope Francis sent me praising the AIDS ministries of people like Carol. And she recalled some more stories from that time, about the trauma and tragedy of AIDS, as well as some of the graced, lighter moments.

During our conversation, it occurred to me how much I owe to Carol. I am far less afraid of identifying as a gay Catholic today because of people like her, individuals who through their own work and witness fought to make the church a more welcoming space.

The history of LGBT people is not widely known, because it often isn’t taught in schools or churches. That ignorance leads to isolation. By inviting me into her life, Carol offered me not only historical knowledge, but a sense that I am not alone in this struggle. She had my back decades before we would ever meet.

Later that night, during my talk, an undergrad at St. Louis University walked to the microphone and asked me how he might go about forming these kinds of friendships. It was a good question, one that I hadn’t been asked in any of my other events. For me, in some ways, it had been easy. It’s not uncommon for journalists to ask people questions about their lives. But I encouraged him to do the same.

Another person I interviewed for the book, whom I now consider a friend, is the Rev. William Hart McNichols. We’ve talked on the phone many times and regularly exchange texts and emails. He’s been another source of inspiration and solidarity for me. But he told me that young people simply don’t ask him about his experience as a young Jesuit priest in the 1980s, trailblazing HIV and AIDS care and pushing for a more inclusive church. I relayed that to the student and encouraged him simply to ask older people about their experiences. He will more likely than not be encouraged by their willingness to share their stories.

Back at Notre Dame, I chatted with a number of students after the talk. One told me he was hoping to work in ministry and was trying to figure out what that would look like as a gay man. Another thanked me for sharing the stories, for offering historical allies as he navigated family dynamics as a gay Catholic. And the young woman, she told me she had actually started considering her faith life more seriously, was considering returning to Mass, after learning about Father Bill, Sister Carol, and the others who fought alongside a community in need.

These stories have the power to change lives. And we owe it to future generations of LGBT Catholics to ensure that they are preserved and passed on before it’s too late.