How a Catholic sister from Louisiana became the American church’s foremost minister to transgender people.

Listen to narration of this article by Adam Llorens, John Dickerson, Anthea Butler, James Martin, S.J., Christine Zuba, Maria Shriver and David Van Biema. (Audio edited by Kevin Christopher Robles.)

Contents

- “Just embrace us. Don’t displace us.”

- “Transgender people are who they say they are”

- “We don’t have a body, we are a body”

- “And you won’t burn in hell”

- “What did God say to you?”

- “Keep going, but be quiet”

- “The nation’s foremost Catholic practitioner of trans ministry”

- “At the core of my being, I am both Catholic and transgender”

- “Have the humility to seek out God’s word”

- “We are the church!”

- Postscript

It was a low moment for Maureen Rasmussen. It was August 2018 and Rasmussen, a devout Catholic who prays the rosary daily, had had a jarring conversation with a priest she had sought out on a deeply personal matter. Rasmussen had struggled most of her life with the gender she was assigned at birth. She had undergone two years of therapy to clarify her personal need for transition. In her late 50s, she had begun taking the hormones that would conform her body to her deep conviction that she was a woman. They had worked. She had started to feel better as a person.

Early on, a priest had encouraged her on her path. “You’re comfortable in your own skin, and God doesn’t make mistakes,” he had said. But now, before she went any further: “It was important to revisit the spiritual thing one more time. Just to make sure I got it right. It’d be sort of like the blessing on top of the cake.” Only this time, there was no blessing. Rasmussen told the new priest, at a Maryland priory, that she was preparing to break the news to her wife. This priest said that the plans were an offense to her marriage vows and her faith. He pointed to a crucifix on the wall and said, “You cannot transition. This is your cross to bear,” she remembers.

“I walked out of there like someone had deflated me. When things go wrong in your life, really hard stuff, you draw on your faith. But when your faith kicks you to the curb when you’re going through it, where else are you going to go?”

Rasmussen went to her laptop, and repeated an exercise that she attempted every few years, despite its not working. She searched for the phrase “Catholic transgender resources.” Historically, this had yielded only crisscrossing polemics and ads for conversion therapy. But something new had popped up. It was a profile from the news site Al Jazeera America. “Call this nun Sister Monica,” it read, “though it’s not her real name.” Monica, it turned out, was a nun at an unidentified location who prayed for trans people and ministered to them according to the gender they knew themselves to be.

Under the circumstances, Rasmussen was not going to be deterred by a pseudonym. She contacted the article’s writer, who promised to forward an email to the sister. Rasmussen wrote: “I am a practicing Catholic, daily Mass attendee and transgender. I pray every day for discernment and good judgment according to God’s will….” She asked whether Monica could assist in her spiritual direction. She signed off: “I will keep you in my prayers…. Have a super day.” And a smiley-face emoji.

“Just embrace us. Don’t displace us.”

Rasmussen is a put-together dresser. Today, she has on tan slacks, a navy top and a striped spring sweater that picks up both colors. On her right hand she wears a small band with a turquoise stone that matches her striking blue eyes. The far shorter woman next to her on a hotel lobby couch in Manhattan—they are attending a conference—takes her other hand. “You were just so incredibly filled with anguish,” says the second woman, Sister Luisa Derouen, O.P.

“When we first started talking, you needed a religious authority. ‘I know I’m transgender. Is this okay with God? I can’t break my relationship with God. Can I still be faithful to God and be trans? Can I be faithful to God as a Catholic?’”

Derouen, petite and trim, has on a black top from Talbots and taupe slacks. (“I can’t afford Talbots. My cousin—I get all her leftovers.”) She wears a small enameled pendant featuring the insignia of the Dominican Sisters of Peace: an olive branch on a black-and-white shield. She goes on, “I asked you, ‘Can you not be trans?’ You said, ‘No.’ Then this is who you are. This is how God made you, and all that God made is precious and good. And God loves you as you are. Being true to that doesn’t separate you from God. It gives glory to God.”

Says Rasmussen, “I had never really heard it from that perspective.”

Derouen still holds her hand. She is a hugger and a holder. She will employ the politician’s maneuver of locking your elbow while looking deep into your eyes. At this meeting, she is 79, but with the relentless energy of someone decades younger. Derouen can do the high or the low: writing essays with the precision and command that reflect her two degrees; or unleashing “Ted Lasso”-isms like “God’s middle name truly is Surprise!” or even more obscure sayings like “They wouldn’t know me from Esmerelda’s cat.” She radiates cheerful optimism but also, a bit disconcertingly, has what spiritual writers call the “gift of tears,” crying whenever certain subjects arise.

The two women chat and banter like sisters but have met face to face just today, after years of remote communication. Perhaps their biggest dual accomplishment, once Rasmussen passed through her dark night of the soul, was her participation in a Zoom group with five American bishops drafting guidelines for Catholic health care organizations on treating transgender people. Derouen did not think any of them had (knowingly) met a trans person. “I wanted them to hear her story,” she says. “Maureen is so Catholic, the way the bishops understand it. Catholic on their terms.”

Rasmussen, who until recently co-owned a successful Maryland-based lighting company (“I brighten people’s lives”) and did a lot of presentations, says she could tell the bishops were listening. When she finished her prepared statement, one of them asked how he should respond if a member of his congregation said they had a trans child. Rasmussen remembers answering, “All you can do is try to embrace it. You don’t have to accept all of it, but don’t close the door on it. That doesn’t work, anyway.”

Rasmussen is a realist. The acceptance of trans people by the Catholic hierarchy, she says, “probably will not happen in my lifetime. But we can’t solve all the world’s problems. If we even do just a little piece, isn’t that something?”

She looks at Derouen. “Just embrace us. Don’t displace us,” she says.

Derouen beams.

“Transgender people are who they say they are”

Luisa Derouen is not the founder of a religious order, and for most of her life she was not an activist, although that changed about six years ago. For a near quarter-century, she has been a lone welcoming face: a Catholic sister since 1961, who has provided spiritual companionship to some 250 trans people, assuring them, person to person, hand on elbow, that they are God’s children. She does not try to talk anyone into transitioning. But she works from the premise that “transgender people are who they say they are” and supports their self-understanding—even as the men who speak for her church have mostly refused.

Derouen’s ministry to trans people began in 1999: the year before the film “Boys Don’t Cry” won Hilary Swank an Oscar and 16 years before Caitlyn Jenner announced her transition. She has been involved only tangentially in the most recent skirmishes over gender-affirming therapy and hormone-suppressing drugs for minors. Her flock consists of an older generation, most of whom spent decades struggling with gender dysphoria before even considering action. They represent a less complicated moment in the overheated national discussion of gender, although they remain deeply vulnerable to its adverse results.

Derouen has invited trans people into her home and church, led them on retreats, marched for their dead and attended their family celebrations. She has taken their midnight calls and helped them come out to their Catholic families. In all these things, she has manifested a radical empathy, sometimes at an emotional cost. Courtney Sharp, a trans activist and Catholic who has watched Derouen’s ministry expand over nearly 25 years, employs an ancient Christian term: “You can see her self-emptying. It’s an elevated, totally unselfish extension of God’s love to others.”

For a long time, Derouen kept her activism secret for fear of repercussions against her congregation, while her reputation in the very small community of openly trans Catholics and their advocates grew. She became the country’s foremost expert on the spiritual component of gender transition. Secular therapists referred clients to her to fill in that blank. Several people testify that she prevented their suicide. Having watched her care for the families of Catholic trans people, the trans writer and athlete Quince Mountain calls her “an incredible ally.” She is also an indispensable historian and catalyst. “She’s a node,” says a trans writer who is still not public about their identity. “If I’m a spoke and I want to find another spoke, I’ll just run it down to her, because most of the spokes connect to her.”

Derouen’s ministry has coincided with a hardening of positions by American Catholic bishops on transgender issues. In 2018, she identified herself; her work became an object refutation of the politicized and abstractly defined stance of much of the hierarchy. She also began speaking out. Two years ago, in reference to some restrictive policies on gender expression in Catholic schools, she told The Associated Press, “You can’t respect people and deny their existence at the same time.” She opined that “there has never been a time in the American church when [the] Catholic hierarchy has had less moral credibility.”

Charles Bouchard, O.P., a priest, moral theologian and health care expert who arranged for Rasmussen’s encounter with the bishops, explains the authority now wielded by a single small sister. “I have never run into anyone with her depth of experience,” he says. “Theologians have thought about this theologically. But her personal contacts and accompaniment make her unique.” When people ask Outreach founder James Martin, S.J., (who commissioned this article) about trans topics, he says, “I always defer to her.”

Three years ago, Father Martin read aloud a heartfelt letter by Derouen expressing her position to Cardinal Giuseppe Versaldi, then the prefect of the Vatican’s Congregation for Catholic Education, during a meeting in Rome. (In 2022, the Congregation was merged into the newly-formed Dicastery for Culture and Education.) More recently, she posted another letter to Cardinal Víctor Manuel Fernández, the Vatican doctrine chief, as he prepared his own document on gender, though she knew her view would probably not align with his. Bishop John Stowe of Lexington, Ky., one of the very few U.S. bishops to offer public affirmation to trans believers, says, “I admire her tremendously. Sometimes the institution doesn’t know how to move forward, and it’s individuals who take a risk and go out on a limb.”

Nathan Schneider, the journalist who wrote that article on Sister Mónica, goes further: “I think Luisa is the church. Because she represents what I think is the church’s true character. That is not a question of what policies the Vatican adopts. Peter denied Christ three times, and the church is always denying Christ. But the church is also manifesting Christ through its saints.”

In a journal she kept for years, Derouen wrote, “Other people may come along later and want to know, maybe, how did the Catholic Church in the U.S. get involved with transgender people?” Her answer? “It started with me.”

“We don’t have a body, we are a body”

Derouen grew up in Welsh, La.—a tiny, mostly Cajun town east of Lake Charles. Her parents were a rice farmer and a homemaker. “I really had a pretty ideal teenage life,” she says. She was “the pretty, popular girl. All of the mothers in town wanted their sons to marry me, or someone like me.” She was her high school’s homecoming queen. Schneider’s article recounted that a blind woman on a bus once said she could tell how Derouen looked just by how the driver talked to her.

There was another side to her, though. Derouen’s mother went to Sunday Mass, and her father didn’t go to church. Yet starting in her early teens, she attended Mass daily. She devoured books from the church library on the lives of the saints and how to pray. And she volunteered as a typist for the Eucharistic Missionaries of St. Dominic, a New Orleans-based religious congregation.

The Eucharistic Missionaries exemplified the expansive spirit of some female congregations even before the Second Vatican Council. Normally, “eucharistic” in a community’s name meant that its primary function was adoration of the Blessed Sacrament. But from the start, the Missionaries understood the term more broadly: as an obligation to be Christ to others, pouring themselves out for the life of the world.

Their chartering documents required them to emulate the servants in Jesus’ parable of the wedding feast, whom the king ordered to “go out to the highways and the hedges” and to “bring in the poor, the crippled and the blind,” among others, to his great celebration. The community taught catechism and adult education in rural parishes. Its sisters also looked to the physical and social well-being of their adopted communities, attending ballgames and funerals and talking household finance at kitchen tables.

Derouen was drawn to them. She yearned to be closer to God. She felt herself to be a “people lover,” as the Missionaries’ vocational literature described its members. One day, a sister took her aside and observed, “You have everything a girl could wish for. Have you ever thought about showing your gratitude and giving it all back to God?” She had now. She remembers thinking, “I don’t want to wake up when I’m middle-aged and realize I’m living a half-baked life. I wanted to be living a full, rich life.” In 1961, to the consternation of family members (an aunt bought her a fur collar in an attempt to convince her out of it), she entered the novitiate right out of high school.

By 1964, when she professed her first vows, the Second Vatican Council had rolled around and she ate it up whole: “I still have my original copy of the documents, underlined.” The Eucharistic Missionaries developed a social justice streak that sometimes put them at odds with more traditional local clergy. Derouen and Dot Trosclair, a good friend from the community, both talk about a 1967 impasse in Welsh. The sisters served separate black and white congregations there, but they wanted to teach all the children together. When the white pastor prohibited it, they took the matter to the local bishop—and prevailed. “When we got kicked out of one place, we went into another,” says Trosclair.

In her first three decades, Derouen worked in a variety of ministries. She embedded in parishes in Louisiana and Colorado, ran religious education programs, organized youth groups and led choirs. (She has a beautiful voice.) She became the community’s vocation director. After earning college degrees in religious studies and then liturgy, she was liturgical consultant in Colorado, Arizona and Australia. She also found she could preach, and was frequently invited to, even though the church limits delivering homilies to priests and deacons. “It would have only taken one person to complain, and that would have been the end of it,” she says. No one did.

Starting in the late 1980s, however, she sensed that another ministry was calling to her. It took a decade to become clear, during which she spent a year in prayer with a community of monastic Benedictine sisters in Alabama, coordinated her community’s motherhouse and did another thought-provoking term directing vocations. She found herself deeply frustrated with the Vatican’s ban on the ordination of those with “deep-seated homosexual tendencies.” Derouen had family members and acquaintances who were gay.

“My friends!” she wrote at the time. “My wonderful, talented gay Catholic friends! How horrible that the church is depriving itself of so much goodness, so much holiness!” She determined that her new call was to a welcoming ministry for gays and lesbians. Her superiors granted permission provided she stayed “under the radar.”

Consequently, the spring of 1999 found her attending a gathering of the New Orleans chapter of PFLAG (Parents and Friends of Lesbians and Gays) when a woman entered and the room burst into applause. Someone explained that this was Courtney Sharp, one of the organization’s national leaders and a transsexual (in the vocabulary of the time), returning after gender-affirming surgery. “I was fascinated,” Derouen remembers, “A transsexual. Here is a whole new slice of life for me!” She was 54, and in the 38th year of her religious life.

Sharp was born in 1953, the second of 11 children in a Catholic family. She had been aware she was different as a child, but she first began looking into gender identity in the mid 1980s. (“I was thinking, ‘Wait! This might not be going away!’”) It was pre-internet, and Sharp finally discovered the work of Harry Benjamin, sometimes called the father of Western transgender studies, in a basement cage for rare books at the Louisiana State University Library. Benjamin, whose best-known patient was Christine Jorgensen, popularized the word “transsexual” and defined the condition now known as gender dysphoria, a mismatch between a person’s sex assigned at birth and their gender identity.

Shortly afterward, Sharp began consulting with doctors and clinical psychologists at a gender clinic in Galveston, Tex. “My hope was to become whole and resolve the inner conflict,” she says. She began her transition in 1992. Like most trans people then and now, she paid dearly for her identity, at one point losing her job and the insurance with which she was paying for treatments. Her faith was vital to her pulling through. “I was looking for certainty in an uncertain world with an uncertain future, and I felt I had to surrender to God,” she says. It was mostly a solo undertaking, as she did not feel very safe confiding in the church.

Long after she had begun a second career, as a notably successful lobbyist for trans legal protections in New Orleans, Sharp continued to believe that a spiritual element is essential to transition. She offered her best advice to several friends trying to maintain faith despite their churches’ disapproval, but she felt that the spiritual aspect was “an unoccupied space.” And then, she said, “Sister Luisa shows up.”

When the two sat down, talk turned quickly to Sharp’s surgery. “I knew I needed it,” she said, “but I hadn’t realized it was that significant.” Derouen immediately responded, “I’m not surprised at all. We don’t have a body, we are a body. We cannot be who God wants us to be without our body. It is hard to imagine how difficult it must be…to feel that your body and your brain don’t match.”

Her remark was not grounded in gender theory, about which Derouen knew nothing. She had not yet hit upon what would become a favorite passage from St. Teresa of Ávila: “Christ has no body now but yours,/ No hands, no feet on earth but yours, / Yours are the eyes with which he looks / compassion on this world.” Trying to explain the moment now, she says that God was pouring love for trans people into her “from the start. And love makes understanding easier.” In any case, both women recall, Sharp sat back in her chair, paused, pointed at Derouen and said, “You get this. You really do get it.” And then Derouen realized: This is what God had in mind for her.

Sharp recommended readings for Derouen and introduced her at various support groups and at an all-trans chat room. (By then there were chat rooms.) She assured her that there was a population of Catholic trans people who would welcome spiritual counseling—although for a while there were no takers. Derouen began holding a “Transgender Awareness Evening” presented with Sharp and several other trans friends, hoping to educate “everyone with an open heart,” as Derouen remembers, but especially priests. One evening it drew nine sympathetic sisters, a sole priest and a tall man Derouen did not know. The group was about to break for refreshments when the man asked to speak.

He said, “My name is Don and I’m a transexual, too.”

Dawn Wright had been the middle of three boys in Mobile, Ala. When Don entered first grade and the children were told to line up by gender, he joined the girls. The teacher told him to stand with the boys. He refused. She sent him to the priest, who spanked him with a wooden paddle “to help you understand the pain of disobeying God’s will.” From then on, Don prayed a rosary each night asking the Virgin Mary to make him happy he was a boy. Like many dysphoric boys determined to conform, he gravitated to traditionally masculine activities: Wright excelled at sports, married the head cheerleader, graduated from the Air Force Academy and flew missions over Vietnam as navigator in a F-4 Phantom II. He succeeded in business and installed his family—he and his wife now had a daughter—in a gated community.

Yet Wright’s radical discomfort only worsened, and after 30 years of marriage she came out to her wife. The marriage blew up. Wright gave up her home and lost her job and insurance. She attempted suicide several times and, not long before meeting Derouen, was living in the psychiatric ward of a veterans hospital.

Derouen estimates that the two of them have logged hundreds of hours since then. Wright’s experience was made more dramatic by unrelated issues. But her story’s essentials tracked to trans life, and especially Catholic trans life, in the second half of the 20th century: childhood confusion, followed by progressive dysphoria, anxiety and depression. There were punishments, threats and simple incomprehension on the part of authority figures, often expressed in the language of sin. The soul-hollowing pressure of suppressing one’s identity was balanced against the fear of losing one’s family, spouse or children if one acknowledged it. Through Wright, Derouen began to understand how fundamentally different trans people’s dilemmas were even from gay people’s. “It wasn’t about who you loved, your relationships. It was about who you were, inside yourself. And it affected everything—everything.”

The stakes were correspondingly existential. The attempted suicide rate among trans people was extremely high. (And it still is. In 2023, The Trevor Project, a suicide prevention nonprofit for LGBTQ youth, found that 48 percent of transgender women and more than half of transgender men respondents said they had considered suicide in the past year. Among the poll respondents, nearly one-quarter of transgender males said they had tried to end their own lives in the previous year.) “It’s one thing to be in a chat room and read what people are writing,” Derouen says. “It’s different to have someone sit right in front of you, with their whole being in turmoil, struggling to live.”

Derouen came to another bitter realization. In her mind, Catholicism, rather than a solace and support, was a bully and a hanging judge. At the time, church teaching offered no policy on gender identity, but many priests treated it as either a subspecies of homosexuality or a bizarre breach of natural law. It was precisely the most devout Catholic trans people—those who, as Derouen puts it, “could not not be either one”—who bore the heaviest burden of presumed sin, guilt and isolation. Wright joked grimly that she was caught in a “Catholic Catch-22.” If she transitioned, that was a mortal sin, and she would go to hell. If she did not transition, she would commit suicide, and that too was a mortal sin.

Like many, she left the church, only to be drawn back in her most anguished hours. Decades after her grade-school encounter with the school principal, she tried explaining to a different priest that she “needed to feel God would understand I must live as a woman if I am to live at all.” His laconic response was that she would always be a man in God’s eyes, and “that I should just look between my legs and I would know that.” She should strive to be a better Catholic. Derouen terms the cumulative effect of these encounters “spiritual rape.”

At the time, deeply concerned but lacking a suitable vocabulary, Derouen sang Wright the Libby Roderick self-affirmation anthem “How Could Anyone?”: “How could anyone ever tell you / You were anything less than beautiful? / How could anyone ever tell you / You were less than whole?” She told Wright to hear the words as if God were saying them to her. (Wright eventually went on to earn a doctorate and teach college.)

The middle-aged sister became a fixture in the New Orleans trans community. National consciousness about trans people—or at least about the rate at which they were being murdered—was increasing. In 2000, Hilary Swank won an Oscar for portraying Brandon Teena, a trans man raped and killed in Nebraska, and in the previous year, activists founded the now-annual Transgender Day of Remembrance in memory of Rita Hester, a murdered Black trans woman. The vigils, which occur on November 20, spread worldwide and featured a litany of the dead. (“My name is Eda Yildirim and I am from Bursa, Turkey. On March 22…my head and sexual organs were chopped off and tossed in a dumpster…”) Sharp and Derouen inaugurated the New Orleans version of the day of remembrance, which commenced at an LGBTQ community center and incorporated a faith aspect as it processed to the French Quarter’s statue of Joan of Arc, the martyr saint of France who often dressed in male clothing.

An increasing number of trans Catholics, and some people from other faiths, sought out Derouen. Within a year, she was seeing about a dozen clients one-on-one. She offered retreats, which were longer, in the small house she shared with another sister. She introduced retreatants to the life of Saint Paul the Apostle, the Black church she attended on the Chef Menteur Highway. If they wanted, they could attend daily Mass with Derouen, join her for gospel choir practice and participate in Friday Stations of the Cross—and feel safe.

Their reception was generally warm and joyful. The pastor, recently arrived from Ghana, had initially been perplexed. But he became a fan, hugging each retreatant on arrival and accepting Dawn’s gift of her now-superfluous male suits. The only friction occurred when another of Derouen’s guests arrived at a decision point and proudly introduced herself at the full Sunday Mass as “Shirley Boughton…a Celtic transgender woman of faith.” That was unusually explicit. A congregant complained, and the pastor immediately convened the parish leaders to explain his expectation that St. Paul’s would be a welcoming community.

Derouen’s relationship with archdiocesan leadership was more complex. In 2003, the American bishops had not directly addressed transgender issues. But they were very cognizant that the Vatican’s Congregation (now Dicastery) for the Doctrine of the Faith (C.D.F.), led by then-Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger, had called homosexuality an “objective disorder” and labeled gay sex as an “intrinsic moral evil.” Derouen’s religious superior, worried that their archbishop might hear of her work through other channels, buried a fast mention in the middle of her annual report: “And Sister Luisa does a ministry of spiritual direction to lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender people.”

The archbishop waited politely and then said, “Now, let’s go back to Sister Luisa’s ministry.” He was concerned it might not comport with church teaching—on gay people. Derouen’s subsequent notes record a member of his staff as saying, visibly frustrated, “You keep talking about love, love, love! You know, what people understand and what you say are sometimes not the same. They could misunderstand you and think that what they’re doing is perfectly alright.” In fact, not only did Derouen feel that God loved gay people as they are, she foresaw that her opinions about transgender people could be far more objectionable.

Eventually, the archbishop made an offer. According to Trosclair, who attended the meeting (Derouen says she does not remember his exact wording), he would approve the ministry if Derouen promised that “at the right time, you teach them the teachings of the Catholic Church” about homosexuality. (Trosclair recalls thinking, “C’mon, Luisa, you can do it.”) Finally Derouen replied, “I will.” Says Trosclair, “Because she knew that the right time would never come.”

One November, Derouen, Sharp and a trans friend drove six hours to attend the Harry Benjamin International Gender Dysphoria Association conference, the bi-annual meeting of health professionals and transgender people held that year in Galveston. Its robust lineup of seminars for physicians, psychologists, lawyers and social workers indicated the extent of the field’s growth. Derouen introduced herself. “I am a Catholic sister. I am here because I have much to learn, in order to be a responsible minister to God’s misunderstood and rejected transgender people. It is a great privilege for me to companion them on their journey. I want to apologize to those of you who have been hurt by the Catholic Church. I do not ever want to hurt you. I want to be a reflection to you of your beauty and goodness.”

This was the first, but not the last, instance of a Derouen-induced double take. A Philadelphia-based therapist named Maureen Osborne remembers, “I had been attending this conference for nine years. They do a long day, and I was sort of daydreaming. I heard a woman’s voice saying she wanted to apologize to trans people for the damage done to them by the Catholic faith. My head swiveled. There’s this tiny woman at the microphone, and I said, ‘I have to meet her.’” Osborne had trans patients with religious issues she sometimes had difficulty addressing. She, Derouen and a sex therapist named Michele Angelo became friends, and the other two began making referrals to her. “That,” says Derouen, “was the beginning of my national ministry.”

“And you won’t burn in hell”

“Bless this night,” says Derouen on the video. She looks much as she does now: compact, pert-nosed, apple-cheeked. Her head is bent down and lamplight glints off her wire-rimmed glasses. The blinds are drawn for privacy.

“Bless these people and their lives. Bless all transsexuals everywhere, especially those who are in crisis and have no place to turn. We ask this in the gracious name of your son Jesus and in the power of his spirit. Amen.” The camera shifts to Nick and Dan, a trans man and his husband, then to Dawn Wright and then to a trans man named Sean.

In 2004, the documentary filmmakers Cindi Creager and Rainie Cole visited Derouen and filmed a gathering of four trans people at her home, then dropped by to visit several more where they lived. The resulting video touches quickly on an array of topics and moods. It catches Sean reliving a moment of liberation. “After I had my top surgery and all, I pulled the drawer open and I said, ‘You guys are outta here.’ I grabbed the bras. I went downstairs and I hummed them over the fence. And then I thought about it for a minute, I said: ‘You jerk. Now you gotta go get ’em and hope nobody’s out there.’” Dawn describes one of her lowest points prior to getting divorced: “My wife, she said: ‘You’re old. You’ve only got a few more years to live. Can’t you just live out your life the way we had planned?’ You know, this dream of a man and woman, walking into the sunset. And I couldn’t.”

Discussion moves to religion. Sean says, “Then they throw the deal in there where you’re going to burn in hell, because ‘you know what you’re doing is a sin.’ [But] I feel in my heart that I’m doing the right thing, so I have to continue. Even if I’m going to burn in hell, I have to continue. Because if I don’t, I wouldn’t survive anyway.”

From off camera, Luisa says, “And you won’t burn in hell.”

Most of the Catholics Derouen accompanied had been molded in faith by The Baltimore Catechism, the American standard of Catholic instruction from the 1880s until 1965. “‘Who made the world?’ Derouen quotes. “God made the world…. ‘What is man?’ ‘Man is a creature of body and soul, and made in the image and likeness of God.’ ‘Why did God make you?’ ‘God made me to know Him, to love Him and to serve Him in this world, and to be happy with Him forever in heaven.’”

“You had to believe this and not believe that,” Derouen says. She smites her desk, a parody of a pre-Vatican II stereotype. “‘If you do this, you’re good. [smite] If you do that, you’re bad.’ [smite] I’m walking on this little path, and if I make a wrong step, a serious wrong step, I fall off. And if I die in that moment, that’s it, kid. Hell.”

Derouen strove to acquaint the Catholics she accompanied with the substantial changes the church had undergone since 1965. Rather than a remote and ever-watchful God, she presented a merciful and loving creator engaged in a dynamic relationship with God’s children as they move through life. “The dance moves this way and that way. And what’s important is that we stay close to our dance partner, God,” she says. Vatican II’s reclamation of the importance of the individual conscience, she explained, delivered believers from simple rote obligation and into a more adult relationship, allotting the church its rightful authority but balancing it with their own experiences and self-understandings.

Thus, trans people could say, “I have gradually come to know my true self, not the self that other people think I am, and to know it is good and beautiful, and that this is who God wants me to be.” To live with honesty and integrity was to be holy. When it seemed appropriate, Derouen would quote a non-canonical document from the early years of the Christian church: “If you bring forth what is within you, what you bring forth will save you. If you do not bring forth what is within you, what you do not bring forth will destroy you.”

“What did God say to you?”

In 2005, Hurricane Katrina devastated New Orleans. The Eucharistic Missionaries moved out of the city. Derouen elected to continue her ministry in Tucson, Ariz. Tucson had an active trans community, and she established herself quickly. The house she lived in had a Spanish-style courtyard surrounded by a six-foot wall, providing privacy. It was at the foot of Sentinel Peak, known locally as “‘A’ Mountain” because of a huge letter A built into it in 1916 by students at the University of Arizona. A local trans man told her, “You’re a safety net. Even people who haven’t been to you know you’re there at the bottom of ‘A’ Mountain.” Part of Derouen’s work involved families of Catholic trans people. Says Quince Mountain, the trans writer who observed Derouen at work, “The idea was, that if this person who is symbolically important in the church can show support, then perhaps my kid isn’t rejecting our tradition and our values after all.”

Derouen counseled people who were not Christian, but some of her deepest work remained with Catholics. Stephanie Battaglino, a former corporate vice president at New York Life Insurance, encountered Derouen at a conference in a by-now familiar way. (“They said, ‘She’s a nun that ministers to the community,’” recalls Battaglino. “I was like, ‘You’re shitting me.’”) Battaglino, who grew up in a working-class Catholic family in New Jersey, had managed her own transition years without recourse to her church. “There was no one there who was ever even remotely interested in hearing about my personal troubles,” she says.

She had begun calling herself a “lapsed Catholic” and attending an Episcopal congregation that was more open about gender, but she was searching for answers beyond churchgoing. “Where do I look for God’s grace?” she says. “How does that work out in the rhythm of my life? I mean, it was like I needed a secret decoder ring. There was no answer for me spiritually, until I met Sister.” During their first conversation, Derouen asked her whether she would like to fall in love with God. “She was cool,” Battaglino says. “We knew she was there to help us. she was understanding of our journey.” A few months later, she joined Derouen in Tucson for a four-day spiritual retreat.

Every morning when it was cool, Battaglino would go running in an arroyo of the Santa Cruz River. After a silent breakfast and some prayer, Derouen would give her Scripture passages or other readings, based loosely on the Spiritual Exercises of St. Ignatius Loyola, to pray with during the day. Battaglino read, prayed, meditated, did yoga (her own practice) and journaled. Each evening they would meet for vespers. The next morning, Derouen would ask, “What did God say to you?” In addition to her faith search, the younger woman was struggling with a professional transition. Having come out successfully in corporate America, she was now considering full-time trans activism. But this would involve becoming a public figure, which was at odds with an ongoing feeling that she was “incongruous,” and with the memory of her late father, who had lived by what Battaglino understood as a Depression-era code of humility: “’There’s really no room for telling everybody how good you are.”

Seventeen years later, Derouen remembers recognizing the humility dilemma as “very much a Catholic thing,” connected to a morality of self that was taught commonly in the pre-Vatican II American church. Selfishness was sinful. The ideal was selflessness, often represented as deferral to the needs of others to a point of self-erasure. This was applied with particular emphasis to women, but also to laypeople in their relations with hierarchical authority. To trans Catholics, it communicated that living out their identity was wrong, to the extent that it disrupted the life of anyone else.

Derouen gave Battaglino a book to read called Healing the Purpose of Your Life, a Jesuit-influenced guide to uncovering God’s “sealed orders” not all at once, but dynamically, over the course of a lifetime. She had her pray on the exhortation in Mt. 5:15 not to hide your light under a bushel basket, but to let others “see your good works and give glory to your Father in heaven.” Battaglino composed a letter to her biological father, crying as she wrote. They delved further day by day. The fourth day was Sunday, and Battaglino attended Mass with Derouen. They talked monthly for years afterwards.

Battaglino became an author (Reflections From Both Sides of the Glass Ceiling: Finding My True Self in Corporate America) and a diversity expert whose recent clients include athenahealth and TD Bank. “The retreat was the catalyst for me to kind of close a chapter of my life where there was a lot of pain and a lot of anguish and whatever,” she says, “and move on into a new chapter where I could truly celebrate myself and the gifts that God had given me.” It was also, she says, the deepest dive she had ever taken into Catholicism. She has stopped calling herself “lapsed.”

In addition to recording her inner life and prayers, Derouen’s own journal entries from 1999 onward function as a sort of panel painting of transitioning lives. The scenes contain considerable pain. They are also shot through with hope and happiness. Derouen shares a meal with a friend who dresses, for the first time, in clothes that feel right. She accompanies another person nervous about using a women’s restroom. A trans man calls from his hospital bed after a suicide attempt; she arrives to find a relative berating him and storming out of the room. A woman seeks assistance for her husband, who has transitioned. After much thought and prayer, the woman herself transitions. Stacy becomes Pete and Mike becomes Liz. (These are not their real names.) Years later, Pete remarries a woman, and Liz serves as his wedding coordinator.

Another couple makes the trip to Tucson: The husband decides he wants to proceed to transition—and the wife announces that if he does, she will leave him. He abandons the effort.

Depressed by reports of an anti-trans document out of Rome, a trans woman asks Derouen: “Jesus chose to die for love of us, so why can’t I choose to die for love of my family, and not put them through this hell and put up with a freak like me?” She pulls through.

Also in the journal, Derouen writes, “These are people on whose coattails I would confidently cling to get to heaven.”

“Keep going, but be quiet”

In July 2002, at a Philadelphia retreat for trans people and their partners, Derouen talked about “claiming life through suffering.” She opened with what, for that group, was a truism: Trans people of faith are told repeatedly that their pain and suffering is God’s punishment for refusing to live as God made them. In fact (according to her notes), “God is not punishing you, but journeying with you, and suffering with you.” The way into a deeper life is through a willingness to die to what keeps us from living more fully. The pain that comes with loving, risking and seeking truth is, in fact, fidelity to the example of Jesus and his redemptive suffering, the being broken and poured out. We are a eucharistic people.

A point she did not raise: What about the person who walks with the sufferers? Who is not actually one of them but exposes herself daily to the pain of the holy community on its bruising pilgrimage? Psychiatrists retire; social workers burn out. Eventually, priests may step back from pastoral work. But what if someone in her late 60s is the only shepherd for a chronically vulnerable flock?

“The stories that Luisa heard,” says Dot Trosclair. “She took it on. And she gave them courage. She suffered with them, and suffering does something. Something happened to her interiority.” Trosclair adds, “The accident had something to do with it, too.”

In 1996, three years before Derouen began her trans ministry, she and Trosclair were driving to Florida. “Something hit the bottom of the car,” Trosclair says, setting off the driver-side air bag. It would be four years before a scan revealed the extent of the damage to Derouen’s face. The initial trauma had set off an arthritic deterioration. The condyle, the part of the jaw that rotates in the socket to allow movement, was now a stump. She was told that she would need a plastic orthotic in her mouth to speak. In fact, she should cut back on speaking as drastically as possible. She found herself in increasing pain.

Her jaw’s slow disintegration coincided with another deterioration: a shift in the church’s perception of trans people from invisible to unnatural. For years, when asked about the church’s stance, she had said there was none—and prayed that the Vatican would consult with medical experts and with actual trans people before addressing the question. Her hopes were shaken in 2003 when the Catholic News Service reported that the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, under Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger, had sent a document sub secretum (under secrecy) to the world’s bishops, directing them not to allow people who had undergone a “sex change” to marry, be ordained as priests or enter religious orders. The reported rationale (the text was never made public) was the C.D.F.’s conviction that the surgical operation did not alter a person’s sex assigned at birth. It viewed “transsexualism” as a psychological disorder. It forbade updating a trans person’s baptismal certificate to recognize such a change.

Derouen’s Catholic trans friends were rattled. Unable to access the document, she searched out a 1997 canon law article on transsexuality by the Jesuit priest who, C.N.S. reported, “largely prepared” the C.D.F. document. She found its science unsourced and its reasoning flimsy. She reassured the people she was accompanying that “this is the first word, not the last word.” But she was concerned. Suddenly, her agreement to remain “under the radar” chafed. She yearned to speak out for the population she knew so well.

And yet the C.D.F. was extremely alert to perceived dissidence, muzzling and sanctioning individuals or groups it felt were deviating from church teaching—and many in the American Catholic hierarchy followed suit. In 2007, Derouen and Trosclair, at that point the Eucharistic Missionaries’ president, traveled to Silver Spring, Md., to ask an expert at the Legal Resource Center for Religious what protection Trosclair could offer Derouen if she ran afoul of the bishop of a diocese where she worked. The answer was none. Derouen could be forced to give up her ministry. Her community might suffer. “Dot told me, “Just keep going, but keep quiet.”

She did, but it haunted her. She equated her public reticence with the closet many of her friends had inhabited. To counsel them to break out while she remained comfortably hidden seemed like hypocrisy. “Somewhere in the world a transgender person is brutally murdered every three days,” she wrote. “But it’s too risky to speak out on behalf of God’s precious people. And I anguish, ‘Is my silence prudence or cowardice?’” She accused herself of practicing cheap charity.

Her trans friends felt she was being too hard on herself. A trans man named Shawn told her, “Well, maybe you call what you do for us ‘charity,’ but your charity is the reason I’m alive today. If it weren’t for you, I’d be dead.” He continued, “If you stand up and carry the banner, you’ll get shot down. And then who do we have?” At the same time, they marveled at her empathy. “It became like the trans experience in proxy for her,” says Sharp. “It’s like, somebody’s going to suffer for a community. They’re going to take on everything that the trans community has. What more could you ask? My heart just broke for her.”

In 2005, Cardinal Ratzinger was elected Pope Benedict XVI. In a Christmas address three years later, he described discourse about gender as an attempt at “self-emancipation” that violated God’s created order and stood “in opposition to the truth.” The remark sketched a theological framework that appeared to categorize gender reassignment as a prideful sin. Derouen, in Tucson, thought it was time for her to “fall on my sword.”

She emailed Bishop Gerald Kicanas of Tucson describing her true ministry and stating, “Once again the hierarchy has exposed its ignorance while alienating so, so many people who are trying their best to live lives faithful to God supported by the Catholic faith community.” That felt right. If the bishop shut her down, she would at least be relieved of her own guilt for her silence.

She says he never responded, although he replied the same day to a note she sent him on a different topic. She took this as a tacit acceptance of her ministry, but chose not to publicize the one-sided exchange. Under Benedict, the Vatican had begun a long-term doctrinal assessment of American sisters, one that eventually led to a partial takeover of the Leadership Conference of Women Religious on grounds of “serious doctrinal problems” regarding homosexuality and the all-male priesthood. The L.C.W.R. represents about two-thirds of the American communities, including Derouen’s.

By 2009, Derouen’s jaw hurt so much that it forced her to temporarily shut down her work. When it happened a second time, she decided to reduce her trans ministry until all that was left was some email correspondence, the occasional phone call and a lot of prayer. She could not pull this off in Tucson, where she was part of the city’s trans life. But the Eucharistic Missionaries, whose membership was aging out (Derouen was by then 64), joined with several other communities to form the Dominican Sisters of Peace, one of whose motherhouses was in rural Washington County, Ky. The Sisters offered her a brown-shingled house with a closed-in porch, next to a cow pasture.

She accepted, converting the porch into a chapel. “I thought this was the end of trans ministry for me,” she says. “I’m going to live in my little hermitage home.” She took a tearful farewell from Tucson, A Mountain and most of her trans friends, and she gave away her books on trans topics. “I am moving from one focused call of God to another,” she insisted. Silence appeared to have won.

“The nation’s foremost Catholic practitioner of trans ministry”

Then one of those macro events occurred that have thousands, if not millions, of micro impacts. In late 2012, Benedict seemed fully committed to his ministry as pope, and had once again assailed “gender theory” at Christmas. Yet two months later, citing frailty and fatigue, he became the first pontiff in 598 years to retire. He was succeeded by the Argentine Cardinal Jorge Bergoglio, who took the name Francis. Francis did not share Benedict’s zest for doctrinal inquisitions, and he dropped the investigation into the American sisters. With the heat off, the leadership of Derouen’s community told her she could write about her ministry—and that others could write about her. Their only requirement was that her real name and that of the community be omitted.

Derouen informed Nathan Schneider, a journalist she had met in Tucson. His admiring, nuanced portrait appeared in 2014 on Al Jazeera’s website. “Sister Monica,” he wrote, introducing her nom de nun, “has allowed Catholics long estranged from the church to start going to Mass again, to regain their faith.” This was the profile Maureen Rasmussen located with her desperate Googling. Others also noticed it. Soon NPR, the Huffington Post and several other outlets ran “Sister Monica” stories.

Derouen was initially happy to have Monica as a cut-out. In the profile, Schneider contrasted her with Sister Jeannine Gramick, who had blazed a trail for Catholic gay and lesbian advocacy. The Vatican ordered Gramick silenced in 1999, and her community at the time forbade her to speak about homosexuality. Rather than “collaborate in my own oppression,” Gramick joined a new congregation and carried on. Schneider observed that “Where Gramick has advocated, Monica has internalized.”

So it was ironic (or possibly simply predictable) that Gramick catalyzed what happened to Derouen next. In 2017, she reported an article about LGBT-friendly women religious for Global Sisters Report that alluded to Derouen without using her name. As a follow-up, Gramick proposed doing a Q. and A. that would out her.

This was—yet again—a risky prospect. The years 2009 through 2016 had been pretty good for trans advocates in the U.S. In 2013, the American Psychiatric Association redefined gender dysphoria from a pathology to just another “human variant,” like sexual orientation. The Obama administration included trans appointees and enabled the ending of a Medicare exclusion of gender reassignment surgery. The number of academic facilities offering gender-affirming surgery for adults increased from eight in the 1970s to dozens, and there was also growth in programs prescribing hormones postponing puberty for dysphoric minors from age 14.

But by 2017, there was a new U.S. president. And a combination of alarm about childhood chemical intervention, conservative concerns about a surge of teenagers identifying as non-binary (those identifying as trans were a much smaller group) and political opportunism fueled a countermovement. In December, 20 religious leaders released a public letter called “Created Male and Female” that dragged gender identity fully into the American culture wars, asserting that “the state itself” must combat it. (Numerous state legislatures have since answered that call.) Four Catholic bishops signed the letter, including the then-archbishop of Louisville, where Derouen’s part of the Dominican Sisters of Peace was located.

Derouen’s religious superiors, while reaffirming their support of her, still felt it was “not the right time” to be open. Derouen, schooled since New Orleans on the indeterminate use of “right time,” wondered whether the moment would ever come. Her answer came from canon lawyers and former leaders of women’s religious communities whom she consulted. Since the leadership’s paramount responsibility was for the safety and well-being of the entire congregation, she was unlikely ever to get permission. “I could appreciate that,” she says, “but I was also looking at the trans community, where people were being murdered. And now people all over the country who knew nothing about them were saying things that could only make it worse.”

She prayed on the dilemma for weeks, finally employing a technique that involves imagining yourself on your deathbed and reviewing your life’s decisions with God. She found herself weeping profusely, saying, “Oh God, I don’t want to die hiding!” She decided to take the decision upon herself. As she later wrote, “As much as a non-trans, cisgender person can experience what they go through, now I was going through it! I was stepping off the edge of the cliff.”

The resulting Q. and A. in Global Sisters Report, in June 2018, was a kind of anointing. Gramick, the path-blazer, called Derouen “a pioneer in the ‘T’ of LGBT ministry,” at a time “when most Catholics were just coming to understand and accept the ‘L’ and ‘G.’” The voice that emerged that day was no longer that of an anonymous sister engaged in pastoral work somewhere “out there,” but of the nation’s foremost Catholic practitioner of trans ministry. It was the authoritative word from the worker in the highways and the hedges, reporting back to the king about the new guests for his wedding. And it was a voice raised in witness as the church, in the eyes of some, continued to malign innocent people. Derouen noted to Gramick that two dioceses had recently sponsored workshops for employees regarding transgender people, but “in both instances the information given was outdated, inaccurate and insensitive.”

To Derouen’s shock, there was very little blowback from the Catholic hierarchy. This may have had to do with some initial confusion about Pope Francis’ views on transgender issues. Francis distinguished himself by his pastoral emphasis—a vision for a church that accompanied more than it condemned. He cared deeply about people on the margins, self-identifying as a sinner ministering to other sinners. This applied to gay people seeking Christ, of whom he famously asked, “Who am I to judge?” and apparently also to trans people. He made history greeting trans groups in St. Peter’s Square, meeting with them in his office and seeing to it that a Roman group was vaccinated during Covid. (Last October, the pope went further, confirming that trans people can be baptized and serve as godparents and witnesses.)

But—as with several issues—his pastoral welcome to the out-group did not extend to altering any doctrine that had made their lives as both Catholic and trans nearly impossible. In fact, when speaking conceptually of gender, Francis doubled down on Benedict’s apocalyptic tone, calling gender theory a “new sin against God” and—severely—a threat akin to nuclear arms.

Like Benedict, he was theoretically targeting an ideology, not trans people. Yet Vatican administrators seemed to blur the distinction. A statement by the former Congregation for Catholic Education in 2014, called “Male and Female He Created Them,” after the description of God’s work in the Book of Genesis, warned of an “educational crisis” brought on by a typically abstract villain: the “ideology given the name ‘gender theory.’” But it described that theory as “nothing more than a confused concept of freedom in the realm of feelings and wants, or momentary desires provoked by emotional impulses and the will of the individual, as opposed to anything based on the truths of existence.” Who could this willful, emotional, contrary “individual” possibly be, other than an actual transgender person?

“Male and Female” also presented fixed gender as the settled science: “male cells (which contain XY chromosomes) differ, from the very moment of conception, from female cells (with their XX chromosomes).” By the authors’ logic, a change in gender identity must therefore be both superficial and voluntary; the document lumped it together with queer identity and polyamory (a relationship involving multiple people). It directed Catholic educators to “provide a solid response” against such “anthropologies characterized by fragmentation and provisionality.”

Derouen objected to “Male and Female” in fundamental ways. To read biblical language as opposed to trans identities, she said, privileges literalism over a believer’s most productive posture toward creation, which is ongoing wonder as its details unfold in their glory. The idea that people became trans on a whim or due to an ideological stance contradicted her 23 years of experience. And she felt that the Congregation’s idea of embryonic development was “far too simplistic.”

She also suspected that although the document’s reach was technically limited to Catholic schools and educators, some U.S. bishops would understand it as a call to broader action. Trans people, she says, were now “on the bishops’ radar, and they felt they had to do something.”

And in fact, in the nine years since, more than 40 U.S. dioceses here have released “gender-limiting” stances, according to David Palmieri, the founder of Without Exception, a network for educators who support LGBTQ students in Catholic high schools. (He is also a contributing writer for Outreach.) Many oppose the use of puberty-blocking drugs and gender-affirmation counseling for minors who exhibit dysphoria. Bishop Michael F. Burbidge of Arlington, Va., declared that “no one ‘is’ transgender.” The Diocese of Fairbanks stated that “a person should accept and seek to live in conformity with his or her sexual identity as determined at birth.” Several diocesan statements directed that, in the words of the Diocese of Lansing, “All school students and their parents will be addressed and referred to with pronouns in accord with their God-given biological sex.” The Diocese of Marquette, Mich., announced that “a person who publicly identifies as a different gender than his or her biological sex or has attempted ‘gender transitioning’ may not be Baptized, Confirmed or received into full communion in the Church, unless the person has repented.”

Outreach contacted several bishops who declined, mostly on grounds of schedule conflicts, to discuss Derouen’s trans ministry or her critique of the diocesan policies. The exception was Archbishop Salvatore Cordileone of San Francisco, who provided a statement asserting that “trans people need to be loved, [but] trans ideology is something different.” He cited a “difference between an ideology itself and caring for people suffering as a result of that ideology.” In an essay on the archdiocesan website, Archbishop Cordileone, addressing gender dysphoria, writes that “[t]he best way to care for people suffering a painful rift between their bodies and their minds is a matter of debate” but also describes trans people as living “at odds” with “[t]he church’s teachings on sex and marriage” by disregarding the “nuptial meaning of the body.”

“At the core of my being, I am both Catholic and transgender”

Derouen says that Archbishop Cordileone appears to be uncertain as to whether trans people are a distinct, identifiable group with authentic identities and spiritual needs, or are rather people misled by an ideology. She regards his apparent treating of trans identity as a variety of sexual orientation as a misunderstanding of church teaching, when, in her experience, many transgender people are not engaged in sexual relationships of any kind. What the archbishop has in common with the authors of the diocesan trans policies, she suggests, is “They seem to have had little or no meaningful experience with transgender people.” As she said to Gramick, “How can [they] minister to people without speaking with them?”

In 2018, she became part of an attempt to change that. Father Bouchard, the moral theologian and health care expert, was then the director of theology and sponsorship for the Catholic Health Association of the United States. He found himself fielding inquiries about trans health care. As both a trade organization and a ministry, C.H.A. represents more than 600 hospitals and 1,600 long-term care and other facilities, the largest collection of nonprofit health care providers in the country. If a new health need is emerging in American life, a C.H.A. provider will encounter it. With increasing numbers of trans people seeking transition assistance and routine medical care, doctors and administrators turned to Father Bouchard for guidance. He also heard from the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops, which was considering a statement on the topic.

Father Bouchard wondered how he could connect with some trans people. He turned to Derouen, with whom he was already acquainted. Soon he found himself sitting down to lunch at a table set for eight. He could not immediately figure out who was trans and who wasn’t. “We were talking about the weather, and about vacations,” he says. “And there was this moment of identification. I thought, ‘Basically, these people are just like me. In some of the ways they live, they are very different, but they are human persons, looking for the same things that I do.’”

When he mentioned this to the bishops, Father Bouchard says, they were “brought up short.” He recalls one of them remarking, “I hadn’t really thought of that, that they have personal lives.” Accordingly, in 2020 he and Derouen arranged a two-hour Zoom meeting with five doctrine committee members and five of Derouen’s acquaintances. Maureen Rasmussen participated. So did Colt St. Amand, a Catholic trans man, psychologist and medical doctor who has cared for dozens of trans people. Also participating were Ray Dever, a permanent deacon with an adult transgender daughter and a woman named Kay with a younger trans child.

The trans people’s side of the conversation is recorded in “Transgender Persons, Their Families and the Church,” a pamphlet released by C.H.A. Derouen opened by saying that transitioning can be “a classic Christian conversion of life, of transformation in God.” Rasmussen told her story, studded with quotes from Jesus, the Catechism of the Catholic Church and the Church Fathers and ending with a request that the bishops “pray for all transgender people seeking truth within the church.” Dever reminded them that trans identity is not a free choice, and that this “has serious implications in the context of our moral theology.” Kay told the bishops that her transgender son had expressed his gender identity from the age of 2, and, as a teen, enjoyed the support of “my entire, large Catholic family” in his planned transition. She described her dismay when her Catholic hospital abruptly discontinued the 16-year-old’s medical care because—as she said an archbishop informed her in a letter—her son had a “confused concept of freedom.” Dr. St. Amand noted that the scientific literature in the last three decades has clarified the neurobiological basis of gender identity and that psychological studies demonstrate the “robustly positive effects of medical and surgical therapies on transgender patients who desire them.” He continued as a believer: “At the core of my being, I am both Catholic and transgender, and I cannot change either, although I have tried.”

St. Amand expressed “great hope that the church will stop the harm it is causing my people and me.” He wondered at some bishops’ rush to judgment, given how little we still know about the wellsprings of gender identity. Historically, he pointed out, Catholicism has found “that there is sacredness in mystery. We appreciate that there are nuances in biblical interpretation, and we are not fundamentalists. …If we can believe in the True Presence when other people say, ‘Nope, that’s just bread,’ we can certainly accept that transgender people are who they say they are.”

The bishops’ side of the event was not recorded. Derouen reports, “They really did listen. They asked genuine questions.” One told her he had been deeply moved. Nonetheless, Bouchard and Derouen agreed that the best they might hope, given the apparent mood of the U.S. bishops’ conference, would be that the doctrine committee simply decline to release a statement. “They finally actually got to meet transgender people,” Derouen said. “But they’re constantly getting bombarded by other people who are screaming in their ears. We pleaded with them, “We don’t know enough yet.’” Months went by, and then years. It seemed as though the bishops might have gotten the point.

“Have the humility to seek out God’s word”

Derouen failed to retire. It turned out that many of the trans people she knew, and many she didn’t previously know, were happy to communicate with her by email, phone and Zoom. After the catharsis of coming out and without the stress of hiding, she discovered that her jaw, while still deteriorating, bothered her less. The drumbeat of diocesan documents demanded response. She filled her schedule with lectures, interviews and essay–writing. Another reason to keep going was the absence of anyone to take her place. Early on, two other sisters had spent a week with her meeting her trans friends, but Derouen gave up the practice for fear of exposure. Now, over four months of Wednesdays, she streamed an entire formation program—15 separate 90-minute instructional segments—for those interested in accompanying trans people.

The presenters were a sort of “This Is Your Life” of Derouen’s last 23 years. Rasmussen talked about faith and spirituality; Maureen Osborne about therapy. Bouchard addressed moral and pastoral issues of accompaniment; Battaglino discussed workplace inclusion. The first, real-time audience was eight religious professionals. Then, in 2021, an LGBTQ-friendly Catholic organization called Fortunate Families built two programs around the videos: a pick-and-choose option for Catholic institutions educating their personnel, and a rigorously monitored 23-hour course with regular follow-ups intended as a formation in the ministry. Within months, 70 people had signed up for the second series.

Says Derouen, pleased, “That torch got passed.”

Father Martin had been in touch periodically with her since 2012. After she went public, he invited her to participate in the Outreach conference and to write for the website. And she did. Martin, who is aware of just three other sisters with trans ministries—ones in Argentina, India and Rome—considers her an advisor. “She is totally ahead of everybody,” he says. “If someone’s been in the rainforest for 30 years, and they say, ‘Don’t eat this plant; eat this one,’ you don’t need to ask questions. She’s been in what is, in Catholic terms, this very new culture, for 24 years. I trust whatever she says.”

One of Derouen’s essays for Outreach, “Four things Catholics need to know about transgender people,” has logged more than 23,000 views. A few months after the Vatican released “Male and Female,” Martin secured an audience with Cardinal Versaldi. The American Jesuit says it was a warm but unusual meeting. He spent most of it reading—in their totality and aloud—letters from a Catholic trans man, the Catholic parent of a trans youth and Derouen. Hers ended: “I beg you… Have the humility to seek out God’s word on this matter from the social and medical sciences that are part of God’s revelation, and from transgender people themselves, who are the Body of Christ every bit as much as any of us.”

Martin posted Cardinal Versaldi’s response, with his permission, the same day. The cardinal was sorry “if people thought the Congregation was accusing people of being ideologically distorted.” Further, Father Martin wrote that the cardinal and an undersecretary wished “to share [those people’s] care for transgender people and want to continue dialogue to reflect on their experiences.”

Heady as that interaction was, last March Derouen and Bouchard found out how little they had influenced the U.S. bishops’ doctrine committee. Through a “Doctrinal Note on Moral Limits to the Technological Manipulation of the Human Body,” it prohibited any interventions, either surgical or chemical, “that aim to transform the sexual characteristics of a human body into those of the opposite sex, or take part in the development of such procedures.” The bishops read the current Catechism differently from Derouen, quoting the passage “’Man and woman have been created, which is to say, willed by God…in their respective beings as man and woman…”

They wrote that any policy of medical intervention that “regards [God’s] order as unsatisfactory in some way and proposes a more desirable order, a redesigned order” is morally impermissible. The note quoted extensively from five popes and the Ratzinger-era C.D.F., but it included precisely one reference to actual trans people—in a footnote. “With regard to those who identify as transgender or non-binary, there are a range of pastoral issues that need to be addressed, but that cannot be addressed in this document,” it reads. It made no mention of the Zoom conference.

Derouen was bitterly disappointed. “For all these years, I’ve been saying, ‘There’s nothing official yet,’ from the U.S. bishops,” she said. “Now there is, and it’s a doctrinal statement. The ripple effect impacts trans people profoundly. People get thrown out of their homes, lose their jobs, lose their families, because of what these bishops say. It’s a disaster.” She sighs. “All I can do is just keep sowing the seeds, to have the energy to stand by what I believe and give witness to what I experience, whether they accept it or believe me or not.”

“We are the church!”

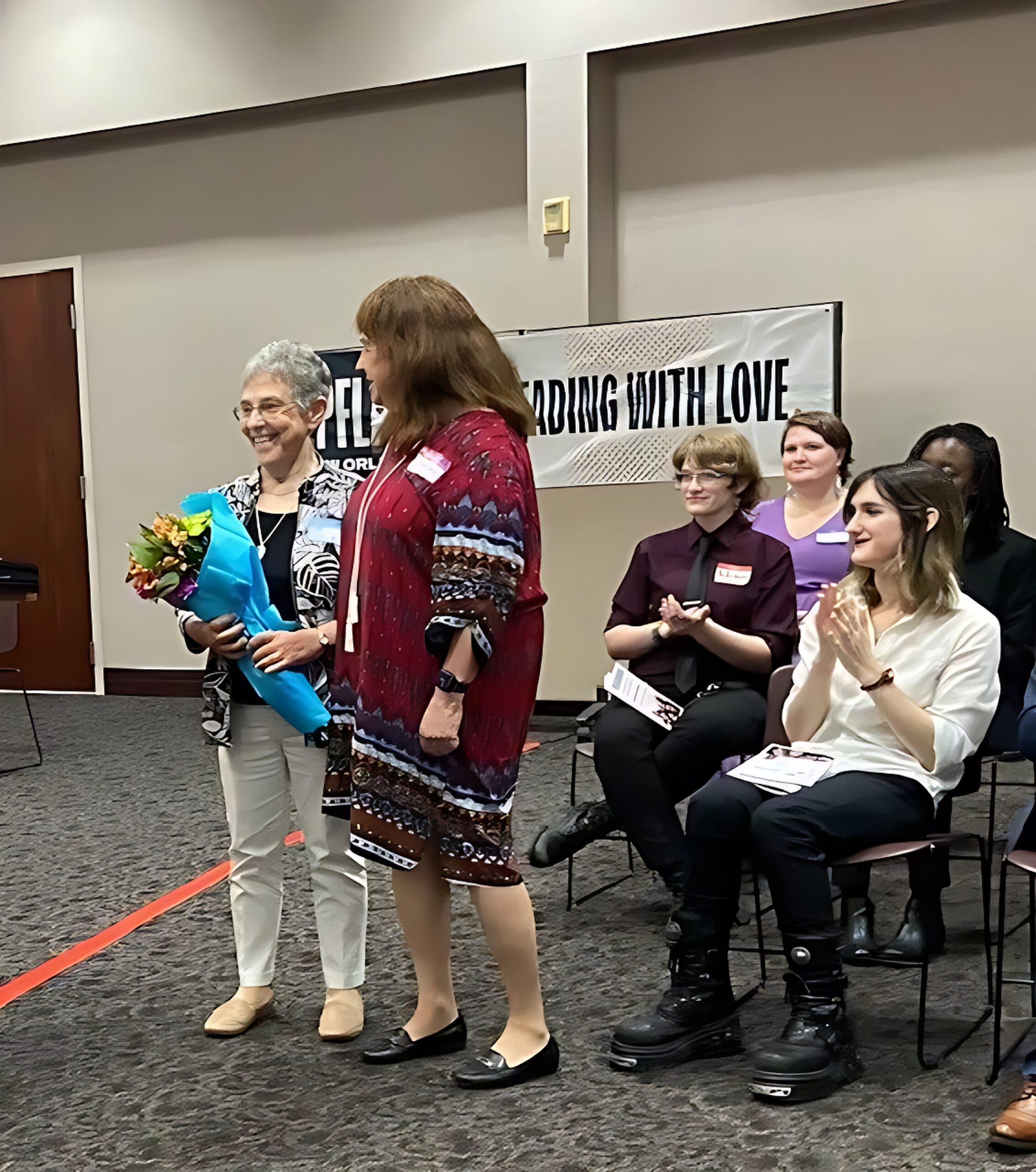

It is a gray, drizzly, early summer day in New York. Derouen, counterprogramming, is wearing a lively turquoise tunic with black pants, ballet flats and her Sisters of Peace pendant. Her transparent orthotic protects her lower jaw. The conference room in Fordham’s Lincoln Center campus is filling with attendees of the 2023 Outreach conference. Last year, Derouen served as a panelist for a breakout meeting on trans ministry that drew 40 people. Today she is leading it, and the audience has nearly doubled.

Also last year, she described the conference as her “last roundup.” Today she’s more philosophical. “I really did give God a blank check from the start,” she says. “I knew my faith would unfold in ways we don’t know and can’t know and shouldn’t know—thank God we don’t know. And we just live into it as we are ready for it.” Her latest informal tally is that there are perhaps 20 bishops sympathetic to transgender rights, out of America’s 290. “That’s sad in some ways,” she comments. “But some people say, ‘Oh wow! Twenty!” She thinks more are “coming ’round.” She no longer stews about possible repercussions of her work. “Before I decided to go public, I was very afraid. I don’t know whether I’m safe or not now, but I’m not afraid anymore.”

Many in the room today would like to feel similarly free. The panelists are Ray Dever, the deacon who participated in the Zoom; Christine Zuba, a trans woman and eucharistic minister in her New Jersey parish and the chair of transgender ministry at Fortunate Families; Hilary Howes, the founder of the website TransCatholic; and Howes’s wife Celestine, to whom she has been married for decades, since long before she transitioned. “Welcome, welcome!” exclaims Derouen. She introduces herself: “I am a Dominican Sister of Peace, and I have had the privilege of ministering among the transgender community for 24 years, and still going.” Someone yells “Amen!” and the room breaks into applause. “And I’m almost 80 years old!” says Derouen. Louder applause and some whoops.

The panelists speak. The room seems like some tiny atoll in a hostile, roiling sea. Somewhere, perhaps, there are campuses full of Gen Z students, some of whose trans and non-binary identities owe much to the age-old drama of youthful independence. That demographic is not on stage. Instead, there are Hilary and Celestine Howes talking about marriage. “Basically, I loved the person, not the genitalia,” Celestine says. Zuba recounts coming out to her 88-year-old mother (“Did you see a priest?” “Yes, Mom, I did”) and urges her listeners to “throw open our doors” and show the world “what it’s like suddenly finding yourself living on the front lines of warfare while trying to get dinner on the table.” Dever explains that his family is having Christmas in Washington D.C., this year because his trans daughter no longer feels safe in Florida. He says it is necessary to recognize that “our church,” even if unintentionally, has enabled “this hatred aimed at a very small group of people who pose no viable threat, and who want to live with the same God-given rights as anyone else… [I]t’s time for this war on transgender people to stop. And it’s time, finally, for the church to get up and do its part to make that happen.”

Amens. Derouen is on her feet. “And this is us, isn’t it! We are the church! Thank you, Deacon!” It’s time for questions. Outside the rain has stopped, although it’s not exactly sunny. Someone in the back cannot be heard. Someone else begins to fetch a microphone. “Let me do that,” Derouen volunteers. She rushes from behind the speakers’ table and into the audience. Her step is sprightly and her eyes bright. She does not look like someone weary from a quarter-century of stressful sharing and a half-decade of uphill advocacy. No, it is as if it were 1961, in Welsh, La., and Luisa Derouen were 17 years old, tossing aside her beauty-queen crown, heading joyfully into her full, rich life.

Related

- The church and the transgender person, James Martin, S.J., May 17, 2022

- I’m a transgender Catholic. This year’s Outreach conference allowed me to be seen, Maxwell Kuzma, August 15, 2023

- I am a transgender Catholic woman, Christine Zuba, June 5, 2022

- I am a Catholic Sister who ministers to transgender people in India, Sr. Prema Chowallur, May 7, 2022

- Argentinian nun who ministers to transgender people with support of Pope Francis: “I keep a record of deaths,” James Martin, S.J., July 6, 2022

Postscript

After editing on this article had closed, the Vatican’s Dicastery for the Doctrine of the Faith released its most authoritative statement to date on gender. “Dignitas Infinita,” written by Cardinal Víctor Manuel Fernández, the dicastery head, with the approval of Pope Francis, addressed the need to protect human dignity. Its final section listed thirteen “specific and grave violations” of that ideal, including war, human trafficking and sexual abuse. Somewhat below came “gender theory” and “sex change.”

The document enshrined as church teaching the arguments expressed in less authoritative or geographically binding announcements, that the field of gender studies promotes “new rights” at odds with the male/female definition fixed by God in the Bible. (“Dignitas” failed to address recent science that might complicate that judgment.) It reasoned—with profound consequences for Catholic hospitals—that “any sex-change intervention…risks threatening the unique dignity the person has received from the moment of conception.”

Like previous statements, it avoided mention of the very trans people whom it will most deeply impact, alluding instead to a nameless class of spiritual offenders. One clause described gender theory as enabling “any individual preference or subjective desire,”as if being trans were a philosophical choice or a transient passion. Another explained that such “personal self-definition” amounts to a surrender to “the age-old temptation to make oneself God, entering into competition with the true God.” Thus, without using the word “trans” (and for that matter, “sin”), the church’s highest doctrinal body assured that nervous priests and bishops, opportunistic politicians and opponents to transgender rights have ample means to deny and condemn trans Catholics for years, if not decades, to come.

Last March, hearing that the statement was nearing completion, Derouen sent a letter to Cardinal Fernández pleading that he see trans people for who they were and testifying that “no other ministry has shown me the face of God the way transgender people have.” Surveying the cardinal’s finished product, she sighs. “I used to say years ago, ‘The hierarchy just doesn’t know who trans people are.’ But that’s changed. They’ve been told. They have heard transgender people’s stories. And while some bishops have taken the time to listen and learn, for many it’s now more of a case of culpable ignorance.”

She has decided not to write about the Vatican statement: “I have been at this for 25 years, using a ton of energy over what bishops say or might say or what they don’t say or waiting for them to say it. I’m at a place in my soul where I can’t keep doing this.” After years of prayer, she has heeded the concerned advice of trans friends and now seems closer to completing her ministry. Fewer write to consult and chew over the latest news. But there are exceptions. On the day “Dignitas” was promulgated, Maureen Rasmussen emailed. Unlike her first message six years ago seeking direction, this one contained no cheery emojis. But it did reassure Derouen that although Rasmussen was “discouraged,” she was “not derailed.”

It helps Derouen somewhat that, with the possible exception of the hierarchy, the Catholic world is much more aware of the existence of trans people than when she started. “Theologians know. The parents of trans children know. People are speaking up and pushing back.” Several trans Catholics in church roles whom she has mentored are moving into advocacy. Last month, Brother Christian Matson, a longtime friend who is a Franciscan Oblate and a diocesan hermit under the authority of Bishop Stowe, announced himself publicly as transgender. Addressing those who might call for his removal or even suggest he does not belong in the church, Matson announced in a Religion News Service interview, “You’ve got to deal with us, because God has called us into this church,” he said. “It’s not your church to kick us out of.”

Derouen says she is reminded of a letter written by the 20th century Jesuit priest and scientist Pierre Teilhard de Chardin to his cousin. (Chardin’s ideas were largely rejected by the church in his day.) “He meant it in a personal way,” she says, “but I’ve applied it more generally.”